What The Matrix Resurrections is telling us: There is no hope for humanity

Lana Wachowski's The Matrix Resurrections combines the ideas of the preceding trilogy and concludes that humans are better off not facing what's real.

- Devarsi Ghosh

Hindustan Times

Last Updated: 12.38 AM, Dec 24, 2021

Spoilers about the Matrix films, including The Matrix Resurrections, ahead.

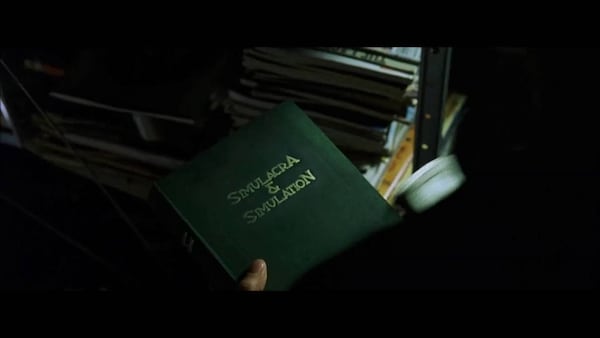

In a 2004 interview, French theorist Jean Baudrillard said, “The Matrix is surely the kind of film about the matrix that the matrix would have been able to produce.” Baudrillard’s theories about simulated realities was a key inspiration for the Wachwoskis' Matrix trilogy, and yet, Baudrillard disapproved of the movies, noting that the Wachowskis missed his point.

While the Wachowskis showed that the real, an apocalyptic wasteland in the faraway future, was clearly distinct from the matrix, a simulation of the world as it was in the 1990s, Baudrillard had proposed that in the postmodern world, the matrix and reality are indistinguishable and feeding off one another until there is no longer any real. There is only a “desert of the real”.

He suggested that unlike Neo and gang in the Matrix movies, we will never be able to escape the matrix or let go of it: our social media versions, our mass media, our sense of selves and the world, as we understand it based on our reflections in the black mirror. Today, we are aware of what the matrix could be, but we are unwilling to log off.

Director Lana Wachowski, one half of the Wachowski sisters, takes Baudrillard’s criticism into account in The Matrix Resurrections, and offers a cynical vision of our world. The film’s most inventive and telling sequence comes early.

This time, Neo (Keanu Reeves) is a video game developer famous for having made the Matrix trilogy of games, whose events closely mimic those of the Wachowskis’ original film trilogy. Like in our world, where the Matrix film trilogy has been highly successful and influential as both spectacle and a reservoir of philosophical ideas that have never been more relevant, in the movie, the Matrix games have had the same effect on the population who are living inside a new version of the matrix themselves.

The parent company of the game makers, Warner Bros., the real-world producers of the film trilogy, has commissioned Neo to make a fourth Matrix game. In a montage cut to Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit, we see Neo’s team break down what made the original games successful.

One says it’s all about “guns” and “bullet time”, the spectacular VFX success from the first film in 1999. Another says it’s “mind porn… philosophy in shiny, tight PVC”. Others say Matrix is about “trans politics”, “crypto-fascism”, “capitalist exploitation”. When someone says reboots are uncool, another points out that reboots sell. Meanwhile, a despondent Neo is seen privately struggling to figure out whether this is all there is to reality.

It’s almost as if this scene shows how the discussions over making the fourth Matrix film played out at the Warner Bros.’ office. The Matrix trilogy is indeed about all the aforementioned things and more, and the fourth film is a reboot-cum-sequel that combines all these elements. Eventually, it turns out Baudrillard was right: the Matrix games were indeed a scam by the matrix itself, to keep Neo’s pre-programmed tendencies and a revolution in check.

The most fascinating aspect of the Matrix films is that while the first movie offered a simple good-triumphs-over-evil story, parts two and three subverted the myth of Neo. In the second movie, The Matrix Reloaded, the matrix’s Architect (Helmut Bakaitis) tells Neo that the machines created Neo as a program to absorb the contradictions within the simulation so as to have human revolutions only help make subsequent versions of the matrix stronger. Neo in the Matrix trilogy is, in fact, the sixth Neo.

In other words, Evil (the machines) has created Good (Neo) within the material world as we know it (the matrix) as a safety valve to control revolutions so that humans continue to provide slave labour. At the end of the first three Matrix films, humans and machines reach a truce. In return of Neo finishing rogue program Smith (Hugo Weaving), who was threatening to take the matrix away from the machines’ control to create a world without humans, the machines would spare the humans’ real-world colony Zion. Neo sacrifices himself to destroy Smith, rescues Zion, and becomes a Jesus-like figure. The plugged-in humans continue to stay plugged in. Those who escaped are allowed to live in peace.

Taken as an allegory of the war against capitalism, it’s a bit like the liberal elite colluding with the capitalistic hegemony to keep the far-right away and help maintain a state of frictionless exploitation.

The fourth film suggests that the matrix has become stronger than ever because of the lessons learned by the machines from the events of the first three films. Now, mass media and pop culture are how the machines (read capitalism), absorb human anxieties and anger and return it as entertainment.

In one scene, Bugs (Jessica Henwick), who leads the mission to unplug Neo from the matrix, tells him as much: “They took your story, something that meant so much to people like me, and turned it into something trivial. That's what the matrix does. It weaponises every idea… where better to bury truth than inside something as ordinary as a video game?”

If Neo, or whoever, encounters cognitive dissonance and are close to realising the truth of the matrix, a therapist pops up to alleviate their anxieties. The therapist here is actually the latest version of the Architect, called the Analyst, played by Neil Patrick Harris. In a fabulous scene (the film’s best scenes revolve around ideas and dialogue; the action is lacklustre), the Analyst tells Neo how in the latest matrix, the machines deliberately trigger human minds to keep them in a perpetual loop of fear and desire so as to make them produce more energy.

He says that “zero resistance” is the best part and that for 99% of humanity, the definition of reality is “quietly yearning for what you don't have, while dreading losing what you do”. The Analyst is talking about our continuous desire to escape power structures (capitalism, patriarchy, caste system, so on) while benefitting from the same structures. With just contemplating or committing inconsequential acts of revolution inside the matrix, but not making any change to material reality, “people stay in their pods, happier than pigs in sh*t,” he observes.

The Analyst’s outlook ties in with late British theorist Mark Fisher’s ideas on “capitalist realism”, which is the unspoken understanding that capitalism is not just the best way possible to run the world, but we also can no longer imagine an alternative to it, just like how both the humans and machines in The Matrix Resurrections who have entered peace time, agreed on the fact that revolutions will only cause disaster. It is the small group of Antifa-like Neophiles who want to challenge this order, but they are no longer supported by their human leaders.

The Matrix Resurrections, especially through the Analyst and the rants of the Merovingian (Lambert Wilson), also suggests that the obvious conclusion for there being no alternative to the present means of production is that there are no new futures, which is another of Fisher’s concerns that he addressed in the essay, The Slow Cancellation of the Future. Fisher writes that the “stasis [of the postmodern condition in the 21st century] has been buried, interred behind a superficial frenzy of newness, of perpetual movement.”

The “jumbling up of time” and “the montaging of earlier eras” in postmodern culture that Fisher finds “has ceased to be worthy of comment” because “it is now so prevalent that is no longer even noticed” is exactly how The Matrix Resurrections plays out literally with Lana Wachowski crosscutting scenes with clips from the earlier films but it is also how the machines in the movie are creating newer versions of the matrix based on older ones, trapping human minds in loops. The Analyst, the Merovingian, and Smith 2.0 (Jonathan Groff) explicitly state that we have reached an ontological dead end, from where it is impossible of think of anything new, as all stories have already been told, all revolutions have already happened.

So, then, is there any hope for a different human condition, one that does not enslave humans with work, entertainment, and relentless serotonin-and-oxytocin-boosting digital triggers?

In the 2006 documentary The Pervert's Guide to Cinema, philosopher Slavoj Zizek said that there is no reason for humans to want to leave the matrix because while “the matrix is a machine for fictions, these are fictions that structure our reality. If you take away from our reality, the symbolic fictions that regulate it, you lose reality itself”. The Analyst tells Neo the same thing, that humans “don't give a sh*t about facts. It's all about fiction” and fiction is guided by “feelings”. This is just one of the several moments in the entire Matrix saga that eerily captures the present-day world.

The answer, then, is no. Humans have no hope. Hope itself is a program, among others, that the machines are cognisant of, can predict in advance, and neutralise.

The final scene of The Matrix Resurrections says as much. Neo and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) have become aware of the matrix, but they realise there is no point in unplugging humanity. The Analyst suggests that the best Neo and Trinity can do is remake the matrix, “paint the sky with rainbows”, because “the sheeple aren’t going anywhere” as “they don’t want freedom or empowerment, they want to be controlled, they crave the comfort of certainty”. Neo and Trinity agree and fly away.

The Matrix trilogy was predicated on the belief that humans want to unplug and face reality. The last 20 years proved otherwise, which is what Lana Wachowski communicates in The Matrix Resurrections. Forty years ago, in On Nihilism, the final chapter of his 1981 philosophical book, Simulacra and Simulation, which is referenced in the first Matrix film, Baudrillard wrote, “the universe, and all of us, have entered live into simulation”. Turns out we love it.

Premium

Premium