Atul Sabharwal's Berlin Is A Slow-Burning Triumph

Berlin takes its time to remind — and remember — of a time in India that resembled little of the place it is now. It's a document of a rapidly changing world imparted through unlikely players.

Last Updated: 10.21 PM, Sep 15, 2024

IN ATUL SABHARWAL'S BERLIN, even the street lights are green. So are the doors, the torch lights, the walls and the cars. Small things — including and mainly colours— function as an ingress to larger contexts of space and time. Set in the world of espionage, the green tinge points to the secrets and suspicion folded in the air. The aesthetic also pays homage to a specific style of filmmaking when film stock with a green bias was used instead of tungsten lights for shooting. Sabharwal’s third feature is a moody capsule of a forgotten era that straddles between tribute and flair.

The year is 1993. Liberalisation in India is underway, and so is an imminent change. The country, however, is caught in the web of the past. Delhi is suffused with brutalist buildings, a post-war architecture holding ground in a newly cordial world. The Berlin Wall has fallen and the Cold War just ended. But India is not the only one held hostage to history. Pushkin Verma (Aparshakti Khurana), a teacher at a deaf school, is also unaffected by the tides of progress. Unlike others, he shows no sign of prosperity. He lives alone and subscribes to a modest existence that comes from seeing others moving past him. His life changes when he is summoned by the “Bureau”.

Sabharwal has a knack for designing narratives from historical strands. In Aurangzeb (2013) the greed of the titular Mughal ruler was used as a metaphor in a portrait of intergenerational crime. Class of '83 (2020) was set in the 1980s Bombay when the city struggled against the nexus of crime and criminals. In Jubilee (2023), a series he co-wrote, the origins of the Hindi film industry were set against a newly formed nation. In Berlin, the filmmaker looks at India through the lens of a freshly concluded Cold War, a timeline so distinct that its iterations are hard to find in Hindi cinema.

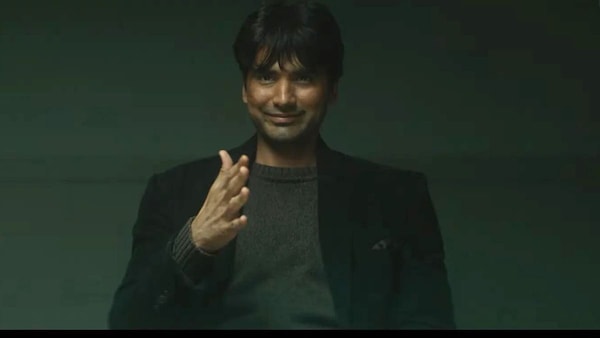

It is his microscopic view of a politically inert time that lends Berlin all the ingenuity. Sabharwal’s Delhi is depicted mostly through closed doors – the interiors of an investigation room or a bare house. The Russian president is coming to India and there is a supposed plan to assassinate him. Although this appears to be the central crisis, the urgency is tied to something else. Pushkin, named after the Russian playwright who was subjected to surveillance, is summoned by the Bureau (headed by an ominous Rahul Bose) to interrogate Ashok (Ishwak Singh), a deaf and dumb waiter. Pushkin is only given questions to ask but no information. In the midst, another agency dubbed as the “Wing” coerces him to ask Ashok the questions they want.

It is a sparse narrative that takes time to reveal itself. Sabharwal, also the writer, does not offer much. The details are scanty. The US and Russia animosity is hinted at, and so is the volatility in Kashmir conveyed through newspaper headlines. The agitation is portrayed at a granular level. Ashok worked as a waiter at a cafe called Berlin that functioned as the meeting ground for people from various embassies. His condition aided the job. In the breeding ground of secrets, he and the rest like him served as walls between people. But the Bureau suspects him to be a spy, and the Wing’s queries are hard to comprehend.

The film unfolds keeping most of the cards close to its chest. In that sense, Berlin qualifies as a slow-burn thriller but it is most exciting when viewed as a document of a rapidly changing world imparted through unlikely players. The internal strife and the competing spy agencies in India add up in the larger picture, but they also underline the existentialism of the world being left behind. As global adversities recede, it is the spies, the foot soldiers, who feel disenchanted. Their identity crisis contributes to a situation that demands the sacrifice of others to preserve their esteem. Berlin, at its heart, inspects the cost one incurs for the price of peace.

For a film marked by such remarkable treatment, it is Ishwak Singh’s silent performance that proves to be the most effective. He lends Ashok a rare dignity that refuses to be dimmed. His eyes glisten as he interacts with Pushkin, taking turns to tease and appease him. In contrast, Aparshakti Khurana, who previously headlined Jubilee and essayed a fictional character based on the real-life late actor Ashok Kumar, feels unconvincing. It is not that his rendering feels hollow but that it is at best functional which only brings notice to the implausible arc of Pushkin from a terrified government employee to a truth seeker in a matter of some minutes. Berlin takes its time though, to remind — and remember — of a time in India that resembled little of the place it is now.

Berlin is currently streaming on Zee5.