Cillian Murphy’s Steve Does The Job

It’s an all-time performance by Murphy, who somehow stages Steve as both victim and survivor in a setting that democratises the nature of suffering.

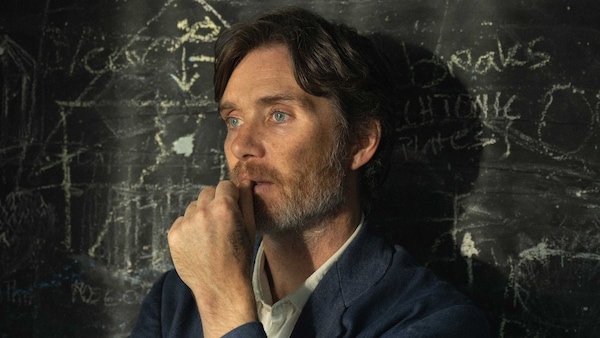

Promo poster for Steve.

Last Updated: 03.17 AM, Oct 04, 2025

STEVE opens with a 48-year-old man (Cillian Murphy) on his way to work. He’s full of nervous energy. The way he’s psyching himself up, you’d think he’s going to war. It’s going to be a long and complicated day. He knows it, not because the film revolves around this day, but because it’s just another day. The moment Steve reaches work, the war begins. As the headteacher of a school of reform for troubled boys, he is pulled into the quotidian mayhem of his ‘job’. The students of Stanton Wood are already at it: Jamie and Riley are fighting like animals again, Tarone is provoking everyone, Shy is brooding and simmering after a heartbreaking phone call with his mother. It’s 1996, and the heavy-metal emotions of youth clash with the hard-rock resilience of adulthood. Steve tries to calm them down, assuage them, warn them, banter with them; he’s everywhere and nowhere.

There’s more to deal with than usual. A television news crew arrives to produce a social interest segment, interviewing the foul-mouthed boys and staff while overlaying the footage with serious questions like “is this a criminal waste of the British taxpayers’ money, or is it radical societal surgery to turn rotten apples into valuable fruit?”. A snooty local politician is expected to visit for a byte; Steve is sure that one of the boys will humiliate him. Steve and his deputy, Amanda, also have an ominous meeting with the State trust that’s funding this controversial rehabilitation program. Add to this the traumatic experience of the newest teacher, 28-year-old Shola, with one of the rowdy students, and an edgy session between counsellor Jenny and another. It’s enough to drive anyone to the bottle, but it drives Steve back to the bottle he had supposedly forsaken.

It’s one battle after another — the teachers are consumed by toxic empathy for the kids that nobody gave a chance to. It’s a lose-lose situation: understaffed, underpaid, highly-strung, dangerous, violent. Yet they can’t imagine being anywhere else. They’re too invested, too deep in the mud to suddenly crave a sense of hygiene and functionality. In most films, a day like this would be a full-blown crisis. In Steve, it’s par for the course. The filmmaking does well to connect our perception of the extraordinary with the characters’ embrace of the ordinary. The camera is restless, shaky and psychologically alive to the mind of whoever it follows. At some points, it does strange and gimmicky things, such as turning upside down and flying out a window across a rainy football field before boomeranging back into the staffroom, almost like it’s teasing the viewer’s notion of how disorienting and dramatic such a place must feel. But there’s something moving about how the camera often stops and stays with a face or lingering feeling — almost as an act of solidarity in a space where the walls seem to be closing in.

Narratively, Steve marries two perspectives: the prison-warden existentialism of Netflix’s Black Warrant meets the institutional teen rot of Netflix’s Adolescence. The teachers want no spotlight, but they share it because they recognise that the boys are not ready to be the protagonists of their own stories. In a way, the adults are broken enough to fix the kids because they’re two sides of the same coin. Some of the exchanges are laced with a sort of surrealism, as if the past and the future of the same lives are colliding with each other, which brings us to the title of the film. The Max Porter novella it’s based on is named after Shy, the soulful boy that Steve describes with a lovely phrase: “generous pain”. But the film is named after the man in charge, the dishevelled and frenetic boss who seems to be suspended in a void between defeat and salvation. It’s not a hijacked gaze; if anything, it conveys the blurring of lines between the ones who bleed and the ones who lead.

Cillian Murphy plays Steve as someone who’s blended in so hard that he’s practically become the very students he was hired to help. Steve is concerned for the boys at school, but his colleagues quietly sense that he, too, is one of the boys. For example, in the scene where the trust informs Steve that they’re pulling the plug on the initiative, he reacts with the kind of physical rage (including a threat to strangle an official) that Shy echoes later during his counselling session. When Steve vents later, he yells into a basement and punches and kicks the air with all the dignity of a man-child with unresolved mental health problems. The students speak to him like he’s the wise old friend in the gang; the reverence makes way for respect. He’s patient and funny with the kids because he relates to them; he’s subconsciously learning how to cope with his own demons through his equations and chats. He’s haunted by an incident from the past whose grief he has buried under the sanctimonious rhythms of his job.

It’s almost like Steve leaves his house every morning — he does have a ‘normal’ home on the side — to enrol in a correctional program under the guise of an intense 9-to-9 workday. The superhero-coded dual life defines the essence of the story: the master was born as the apprentice. The chaos is his therapy; it’s what keeps him sane with his family, and his reaction to the closure suggests that he needs the school just as desperately as the boys do. It’s an all-time performance by Murphy, who somehow stages Steve as both victim and survivor in a setting that democratises the nature of suffering. His body creaks under the weight of the world on his shoulders, yet he moves as fluidly and unpredictably in the corridors as the students: always a step ahead of his colleagues in breaking up fights, always a word closer to the kids when they lash out. The film ends with a sliver of hope after being generous with its pain for 90 minutes. Steve’s identity expands beyond the tattered cape he wears. It’s been a hard day’s night of nurturing; it’s been a hard day’s night of belonging.

Steve is currently streaming on Netflix.