Dhadak 2: Shazia Iqbal’s Caste Drama Offers Course Correction

Dhadak 2 borrows its beats from Pariyerum Perumal but vibrates with its own music. It is a tender task, situated between adapting and creating, performing and inhabiting, miming and mining.

Last Updated: 07.36 PM, Aug 01, 2025

SHAZIA IQBAL'S Dhadak 2 stands on dented shoulders. Like its spiritual predecessor, Dhadak (2018) — adapted from Nagraj Manjule’s Sairat (2016) — it too borrows the contours from another language film, Mari Selvaraj’s Pariyerum Perumal (2018). This baffling practice of sharing genesis with acclaimed sources renders the franchise open to closer scrutiny and resistant to unbiased engagement. Observations are accompanied by comparisons, and every question heads in a similar direction: did it improve on the primary material?

With the first film, the query was easy to resolve. Shashank Khaitan’s Dhadak reduced Sairat’s caste struggle to a homegrown class difference, making even the impending tragedy feel facile. Iqbal’s film, however, puts forth a more complicated proposition. Hers is a more faithful rendition of the original and by virtue of that, a rare mainstream Hindi film to tackle caste politics with central force. Dhadak 2’s distinction then is reiteration — an audacious task still, reflected in the 19 cuts the film accrued from the CBFC, ranging from blurring of casteist slurs to references to caste. The certification board’s cageyness has the most strident representation in the opening disclaimer that claims everything in the film to be fictional — the city it is based in, the depicted violence, mentions of suicide, etc; the denial is no different from Hindi cinema’s long-standing propensity of looking away from caste-based issues. Emerging from this darkness, Iqbal’s film offers a course-correction.

Dhadak 2 borrows its beats from Selvaraj’s film but vibrates with its own music. It is a tender task, situated between adapting and creating, performing and inhabiting, miming and mining. Iqbal, who helmed compelling short films in the past, balances with expert skill. In her able hands, Dhadak 2 straddles between a retelling and an original, using the Tamil outing as the base and springboard to broaden the scope of politics as the narrative shifts from the south to central India.

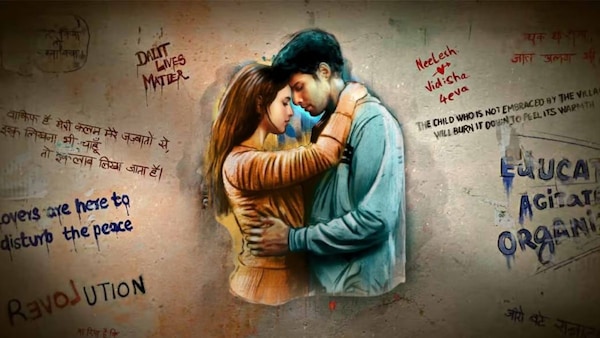

Neelesh (Siddhant Chaturvedi) and Vidhi (Triptii Dimri) meet in college but see each other elsewhere. She is dancing at a wedding, and he, with his small boy troupe, is playing dhol. When asked if he will play at her sister’s wedding, the suggestion is gladly obliged. Another Hindi film hero would have brushed this off as a mix-up (and be revealed to be the groom’s friend in all possibility), but their confusion is Neelesh’s reality. He belongs to an oppressed caste, unlike Vidhi.

In hindsight, this remark sharpens to be an argument. Much like Pariyerum Perumal, Neelesh and Vidhi turn out to be classmates at a law college (the setting is Bhopal, but no city is mentioned). He struggles with English, and she helps him. Soon, they fall in love and seal it with a hesitant kiss. An invitation to her sister’s wedding follows, and so does humiliation for Neelesh at the hands of her cousin. Selvaraj staged it with an incendiary moment, revealing it here will be a spoiler, and though it is replicated in Dhadak 2, it appears muted (probably because the shot is censored). Iqbal halts longer at Neelesh’s inconsolable breakdown, stinging as he is with indignity.

Post the wedding, Selvaraj’s film includes more violence directed at the protagonist by upper-caste men as the girl dwindles in the background. Iqbal brings thoughtful changes without altering the core. In Dhadak 2, the college refuses to serve as an ironic setting, an educational site breeding with caste-based atrocity. Instead, it opens up as a space rife with student politics distilled in the fiery speeches of the Dalit leader (Priyank Tiwari; imbued with the eloquence of Kanhaiya Kumar), arguing in favour of reservation and fellowship. This literal presence of caste politics not only eases Neelesh’s alienation but also underlines his personal experience to be a shared reality.

If Iqbal and co-writer Rahul Badwelkar lend character to a physical space, they extend similar care to characters. The sympathetic principal in Pariyerum Perumal is written as a Muslim man in the retelling (a terrific Zakir Hussain as Haider Ansari), the shift in identity contextualising his empathy for someone as disenfranchised as Neelesh. The filmmaker carries this forth in her thoughtful remodelling of the female characters, accounting for the most tangible improvement on the original. Both Neelesh’s mother (Anubha Fatehpura) and Vidhi are women who refuse to be sidelined. Their solidarity is more tactile because their existence is just as mired with gender.

Especially Vidhi. Unlike the female counterpart in Pariyerum Perumal, she is more aware and informed. She charges at her brother, argues for Neelesh with a biased teacher. When asked why she broke up with her previous boyfriend, she quips, “toxic masculinity”. Her verbose defiance is a departure from Selvaraj’s film, and loves so perfectly that it threatens to flatten Neelesh’s truth as a mutual existence. Most things point to this. Other than a conflating title like Dhadak, a large chunk of the first half carries the breeziness of a Dharma film. They hold hands and kiss, share old sorrow with the urgency of fresh grief – when he shares the appalling way his dog was killed (by upper-caste boys), she tearfully shares how her mother died. The musical interlude in the background gains steam to erupt into songs, but rarely does.

One of the more striking things about Iqbal’s debut feature is her discerning empathy and never losing sight of whose story Dhadak 2 really is. The second half proves to be instructive. As caste-based cruelty against Neelesh intensifies on the campus, Vidhi’s dissent sharpens. She throws a fit at home and reassures him that nothing else matters to her. She repeats the same words when Neelesh shows his ghettoised neighbourhood — her denial sounding more like caste blindness.

That her reckoning never comes (in the post-credit scene, she holds Baburao Bagul’s When I Hid My Caste: Stories – possibly an indication of curiosity) and bravado yields little result (in a significant shift, Vidhi is told about her father’s involvement in the wedding incident and although she goes off to confront him, she never does) reveal her rebellion to be rehearsed. It is not imperfect but inherited from the books she reads and the films she watches. Her theoretical awareness makes her attuned to something like “toxic masculinity”, but blinds her to her father’s caste prejudice (essayed by the ever-effective Harish Khanna). Therefore, in hindsight, on their first meeting, she had looked at him with the acceptance of a heroine in a fiction film, and he tried to fit in thereafter. His idealism only jolted on the wedding day of Vidhi’s sister, where, when still optimistic, he wore a jacket like Shah Rukh Khan in the cross-border love story Veer-Zaara (2004). As if, for a while, Neelesh too had simplified social conflicts in his head, like a movie character trained to be in pairs.

Even when they forget the story they are in, the filmmaker remembers. Her intrusions are slight, like letting Vidhi take the lead when they both start falling for each other. She kisses, he follows; she falls in his arms, and he holds her after dropping her the first time. Like Pariyerum Perumal, one of the more intriguing characters in Dhadak 2 is an honour killer, Shankar (played by the super effective Saurabh Sachdeva), who dispenses free service for cleansing the society. Lurking in the background, his deeds interrupt Vidhi and Neelesh’s love story and the likes of it. Iqbal flips it soon, signalling love to be the interruption to caste-based outrage, depicted in a chilling shot when the camera follows Shankar in the frame even as the leads exit. In fact, the film opens with him.

Everything else is dressing. It is an informed call from the filmmaker that influences the performances. Dimri inhabits a meatier role after long, and is largely adequate, if monotonous. Chaturvedi, however, is tremendous. His brown-face is unnecessary and distracting, but the actor’s physical performance goes beyond the trappings of victimhood. He essays Neelesh like a man forced into heroism and whose rite of passage awaits the film. There is no excess to his portrayal, as if he is hesitant to claim the rights to his story.

But Dhadak 2 does. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar’s pictures adorn several background scenes in the film and blue, the colour associated with the leader, leaks into the frame. One could call it performative but when symbolism gains the mileage of context, even tokenism gains emphasis. Like a Dalit character in a mainstream Hindi film breaking the fourth wall — a showy moment in isolation but momentous in a film like this.