Dharmendra: The Star Who Finished His Arc Early & Let The Myth Stand Alone

Long before the action-hero silhouette calcified around him, Dharmendra was the quietly magnetic presence at the centre of some of Hindi cinema’s most tender moments. Vikram Phukan writes.

The first half of Dharmendra's career remains one of the most potent stretches any Hindi film actor has managed.

Last Updated: 07.31 PM, Nov 24, 2025

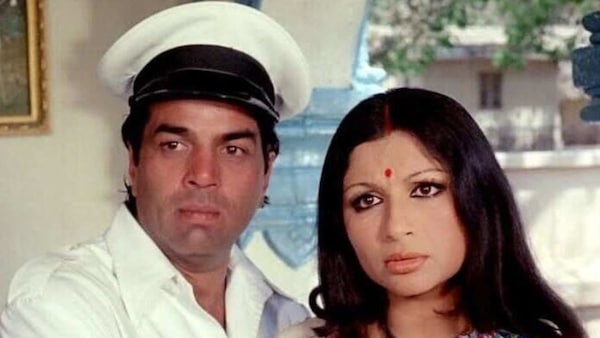

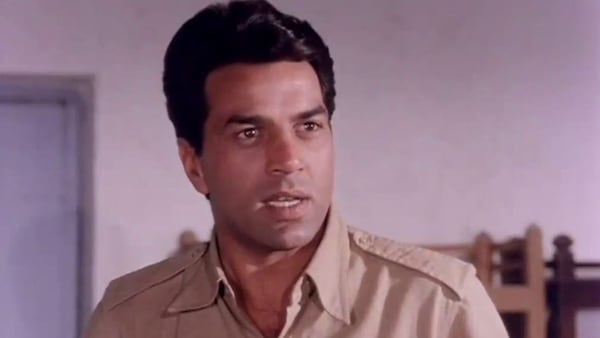

AS WE LOOK BACK at Dharmendra’s career, that of one of India’s most enduring leading men, perhaps the defining image is that of a pioneering action hero. This is partly because the 1975 classic Sholay looms so impressively in his legacy. That film allowed him to lean into easy humour, into that outdoorsy masculinity audiences adored, and into the charmingly roguish romantic figure he had already perfected elsewhere. There is also the notion that his Veeru was mainly the buoyant counterpart to the gravitas of Amitabh Bachchan’s Jai. Perhaps this has more to do with how Bachchan’s later superstardom reshaped memories of the 1970s, and it is telling that Dharmendra ended up doing only one more major film with him afterwards (Ram Balram, 1980). But Sholay gave Veeru a clear emotional and moral arc, and beyond the widely cherished comic scenes, many with long-time collaborator Hema Malini, he also anchors some of its most emotionally decisive moments, showing how comfortably he held multiple tones in a single frame. As the leading man who ‘didn’t die’, Sholay was first and foremost a Dharmendra vehicle, sitting at the centre of his screen persona, just as his Veeru was so unmistakably central to the film’s lasting power.

For many of us who grew up in the VHS-saturated 1980s, Dharmendra was less a distant superstar and more a regular presence in our living rooms. Commercial fare seemed black-listed on Doordarshan, so we consumed them in movie marathons at home: a month of, say, Tarzan films, a Bachchan binge, a notorious run of horror titles, and always, somewhere in the pile, a Dharam-Hema film. The two appeared together as a romantic pairing in roughly twenty-six films, a number that made its way into the Limca Book of Records. Many of those films were playful and high-spirited but also eminently forgettable, like episodes in a long-running series rather than cinematic totems in their own right, held together more by the charm of their chemistry than by the sturdiness of the scripts around them. Malini, in particular, carried a lighter, more instinctive energy opposite him. What they built was a reliable, low-stakes comfort zone rather than a defining artistic chapter. Two titles in particular linger in memory, more as answers to a trivia question than anything. Dillagi (1978), their soft, gently observed Basu Chatterjee romance, cast them as professors, and was allowed on Doordarshan (its VHS tapes were harder to come by in Shillong, where smaller films didn’t always reach the video libraries). And then, much later, the action-packed Jaan Hatheli Pe (1987), now remembered, if at all, as their final stand as a screen couple.

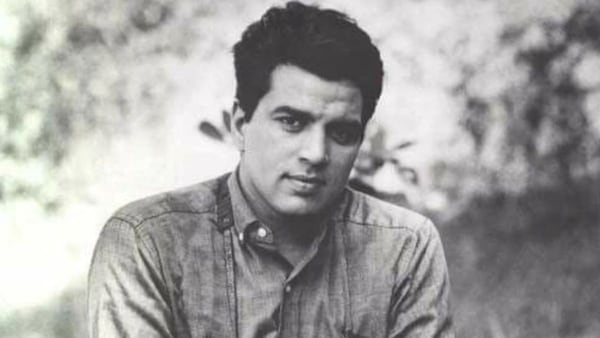

Dillagi’s gentle rhythms showed Dharmendra performing in a low register that might seem unusual today, but it was very much part of the soft-spoken, dreamy persona he first brought to the screen. Long before the action-hero silhouette calcified around him, he was the quietly magnetic presence at the centre of some of Hindi cinema’s most tender moments. One of the earliest images we retain is from Anpadh (1962): the newly-wed husband who becomes the object of Mala Sinha’s yearning in the monumental Lata Mangeshkar melody 'Aap Ki Nazron Ne Samjha', only to disappear from the story straight after, leaving the song to carry the weight of his memory. He brought a similar gentleness to Bandini (1963), playing the kind, benevolent jailer who would have made a perfect companion for Nutan’s restless Kalyani. Even as a newly debuted actor (he entered films in 1960), Dharmendra commanded enough presence that these smaller roles remain vivid in memory.

Director Hrishikesh Mukherjee understood this early, inward-facing quality better than most. In his Anupama (1966), Dharmendra plays the idealist poet who refuses to be jaded, almost in the Guru Dutt mould, without being derivative, and anchored so wonderfully by Hemant Kumar’s 'Ya Dil Ki Suno'. Mukherjee would go on to direct him in Satyakam (1969), the unacknowledged tour de force of both their careers. In Guddi (1971), Dharmendra appeared as himself, warm, playful and empathetic, a gentle prankster who demystifies his own stardom. That easy wit and generosity of spirit would sharpen into full comic bloom a few years later in Chupke Chupke (1975), where he played the widely remembered botany professor Parimal Tripathi with the same good-natured mischief opposite an equally effervescent Sharmila Tagore, both of them far removed from the introverted young leads they played with such unshowy assurance in Anupama. These shifts weren’t abrupt; they chart a steady widening of his range without losing the core quietude of his early years.

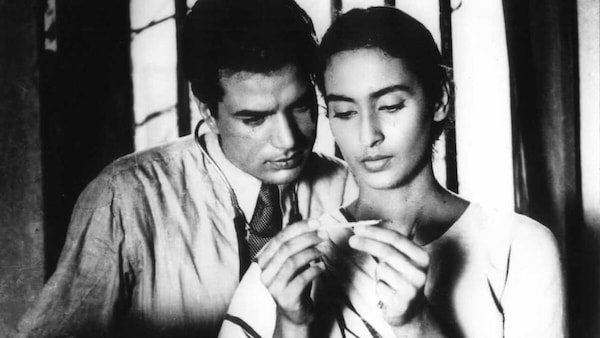

Satyakam was the film that carved out Dharmendra’s moral seriousness without the swagger that would later define him for another generation. In it, he plays Satyapriya Acharya, a man for whom truth is not a choice but a burden. Based on a novel by Narayan Sanyal and entrusted to Mukherjee’s steady craft, the film asks a simple but daunting question: Is a life lived by ideals worth the cost? Here, Dharmendra is not thrown into gunplay or spectacle; he is challenged by friendship (Sanjeev Kumar, later Sholay’s Thakur), by love (Tagore) and by the weight of his unshakable principles. Mukherjee himself described the film as among his most fulfilling, and critics still point to Dharmendra’s performance as one of his most complete. The man built for larger-than-life heroics becomes quietly heroic instead, and that quiet is what stays.

Although Dharmendra kept working through the last three decades, his essential body of work was long behind him. The first half of his career remains one of the most potent stretches any Hindi film actor has managed. Very few stars define the entire emotional bandwidth of their cinema and then step away from the centre without tarnishing the legend, and he was one of them. He never constructed a second-wave persona strong enough to overwrite the first, the way some of his contemporaries later did, which is why the memory of his prime remains so clear. That’s the man people are likely grieving today, a star who completed his arc early, left the myth untouched, and let it stand on its own for the rest of his life.