He Was A Friend Of Mine: Notes On The Banshees Of Brotherhood

Rahul Desai writes about rediscovering the grief and solace in The Banshees of Inisherin after a personal bereavement.

Last Updated: 02.09 PM, May 07, 2023

This is #ViewingRoom, a column by OTTplay's critic Rahul Desai, on the intersections of pop culture and life.

***

IN MY HEAD, I’ve nurtured a very cinematic image of retirement. I live in a quaint hilltown with my partner. We spend our time reading, talking, cooking and taking long walks around our cottage. But we aren’t alone in this town. My best friend — a man who’s living evidence that buddies can be soulmates too; a guy I’ve seen the world with — lives a few doors down. The two of us didn’t just happen to stay in the same place; we planned it decades ago. So we meet at the local bar for exactly two beers every evening. We play cards. We listen to music. We discuss the good old days. Then we go back to our respective homes, tipsy and satisfied with the surety of our bond. We’ve earned the muscle memory of this regimen; we’ve worked to reframe mundanity as the medicine of familiarity. Come hell or high water, that one hour at the bar is non-negotiable. It doesn’t need a text message or a phone call — it’s like strolling into your bedroom after dinner without even realising it.

In my head, I knew who this friend would be. Over the years, our compatibility and chemistry led many to think we were romantically involved. This was not only a compliment, but also an amusing signpost of a shared tomorrow. That bar definitely had a table with our names on it. One of my favourite moments from our travels features a night in faraway Riga. We had spent the day doing separate tours. We were supposed to meet near a landmark at sunset. But a slight misunderstanding meant that we lost ourselves in the tourist rush. More importantly, neither of us had international sim cards. There was no cell coverage; we had no maps to work with. The only way was to walk all the way back to the apartment and hope for a coincidence. While I contemplated every shorter option, I popped into a basement pub to escape the cold. And there he was — trying to catch a WiFi signal near a window. Of all the cosy escapes in the city, we had chosen the same one. It was meant to be.

So when he was diagnosed with leukaemia in 2020, my first reaction was to protect that future I fantasised about. It was selfish, but back then, it wore the cape of selflessness. It was going to be an uphill battle for him. So I kept hinting at the comfort of long-term togetherness. I assumed that perhaps it would be soothing for him to hear that we were going to come out of his cancer as the same friends that went in. Sometimes I spoke about how brotherhoods thrive on routine, citing the example of MacLaren’s Pub and the How I Met Your Mother gang. Sometimes I spoke about our Mumbai drill of drinking on Tuesdays to create the illusion of a weekend within the week. Sometimes we joked about how his chemo cocktails would have to replace our alcohol sessions.

By 2022, he was in remission for the second time. Much of the year was cancer-free. However, his reading of routine — and sameness — had been inextricably altered. After months of hospital rooms and pills and radiation cycles, I sensed the restlessness to move. To do. To just be. Naturally, he became a newer person with newer priorities and expectations from life. As an old friend it was exciting to see, though I did suspect that I might need to recalibrate that hilltown future. I don’t think patterns were so soothing anymore. I don’t think curated monotony sounded all that attractive anymore. To be honest, it felt like a tiny price to pay — this renegotiation with my idea of attachment — in return for his good health. Seeing him renegotiate with the very language of living — with food, drink, travel, work, family, holidays, words — put my fears into perspective. I was learning to trade the shape of my fantasy for the shapelessness of our reality.

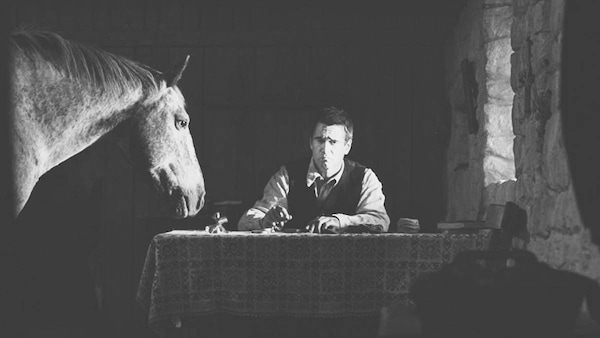

When I watched The Banshees of Inisherin late in the year, it felt uncanny at first. The cottages, the empty tranquillity, the pub, the set ways. This is how us city-slickers imagine the ‘afterlife’. In the film, a middle-aged man named Colm (Brendan Gleeson) abruptly stops talking to his best friend, Padraic (Colin Farrell), on a fictional isle in 1920s Ireland. The reason: Padraic is not interesting to him anymore. Colm, a folk musician and a thinker, feels like his life has slipped away between Guinness pints with Padraic. Their routine has left Colm no room for intellectual growth and curiosity — he now wants more, and the sheer simplicity of Padraic’s company is holding him back. Colm’s morbid stubbornness and Padraic’s unravelling chisel out the soul of a film that transcends its Civil War allegory to emerge as a study of bonding in the time of historical boredom. Padraic is essentially mourning the death of a friendship — gearing through the five stages of grief — until he morphs into a rawer person. It’s the human equivalent of a man painfully mutating into a werewolf, a wild beast, after being contaminated. Most people lose their mask and reveal their real selves, but Padraic loses himself and grows a hostile mask. He becomes edgier, which is ironically what Colm thought he always lacked.

As strange as it sounds, Martin McDonagh’s pitch-black dramedy made me more alive to our situation. I wasn’t Padraic and my friend wasn’t Colm, but I was aware that things were no longer the same. We were adapting to a truth that came without warranty. There were more “ifs” than “when” in our chats. I felt guilty for travelling with my partner, because it felt like I was ‘moving on’ during my friend’s treatment. But I also knew that he didn’t want me to wait, because a stroll on the beach now meant just as much to him as a flight to some obscure country. Bit by bit, I learned to cede space and make peace with my flexible role in his journey. I recommended the film to him, too, wondering if he would detect my neediness in someone like Padraic. I don’t know if he watched it, but I viewed The Banshees of Inisherin as an extreme version of growing apart — something I was afraid might happen to us.

At that point, I behaved like the cancer was gone for good; he had beaten it. All we had to do was find a new social grammar. Maybe I could get edgier, or maybe I could adapt to the more philosophical conversations he enjoyed having. As a culture, we tend to associate friendships with the freedom to be mindless and weightless — an escape from the bags and baggage of daily living. But here perhaps it had to be the opposite. My thinking cap had to come on during our video calls, because he was not seeking a midnight swig or an exotic trek anymore. There was a sense of depth and wholeness to his exchanges now, a bit like if Colm were to compose a song and expect Padraic to engage in a critical and thoughtful manner. I got a little smarter after every call with him. I was changing to keep up with him.

2023 brought with it another relapse. Nobody panicked. We spoke less, but I was convinced that he was trying to get on with it without worrying us too much. I felt confident that he was just protecting his friends from their own fragile heads. In my most vulnerable moments, however, I fretted that perhaps he was subconsciously creating a distance so that it wouldn’t hurt as much if the closeness collapsed. Perhaps he was that compassionate. Every now and then, the overthinker in me came to the fore. I wondered if I was going to be too vanilla, too basic, for him after all his physical and emotional turmoil. Cancer is the real deal, while people like us only speculated suffering and approximated agony. He was bound to feel alone, the way most survivors do after they scale superhuman peaks of pain. Whiling away time at pubs was not going to be his idea of catharsis and peace anymore.

He passed away in March. It’s not too long ago, but I remember all that pent-up edginess in me bubbling up to the surface. I don’t think I was a nice person to be around. I resented others for not understanding this loss; I allowed myself to be irrational, aloof and, at times, rude. As far as I was concerned, this was about me and nobody else. Some strangers and friends were mature about it. They let me be messy. They let me lash out. Especially the ones who had experienced heartbreak and tragedy of their own. But an old friend cracked under the pressure of my selfishness and insisted that I was ungrateful for his generosity. (I didn’t know adults kept accounts.) Fortunately, the numbness of losing a loved one made me immune to his cruelty. I was wearing a shield of hurt; nothing and nobody was going to penetrate it.

Over the days, I wrestled with the most recent version of myself. The Banshees of Inisherin became a different film to me. In my head, it’s now about Padraic grieving the actual death of a friend. Colm is no more, and Padraic — being the sheltered islander that he is — spends the entire film struggling to confront the void. By visualising Colm alive and rejecting him, Padraic is merely rationalising the demise of his best friend. The fingers Colms cuts off is perhaps Padraic’s way of coming to terms with a violent accident that may have killed his pal. The village plays along to cushion his fall. The grief consumes him so hard that his sister Siobhan leaves. He is so deluded that even his little donkey, Jenny, dies in his neglectful care. A lonely Padraic burns down Colm’s cottage in a fit of rage, punching through the clouds of his own innocence. The ghost of Colm’s absence haunts him into the shadows. Padraic lets the friendship live on — manufacturing lofty tales of revenge, estrangement and redemption to aid his own emotional evolution. The story is in the subtext: The death of Colm breaks down the old Padraic and rebuilds him as a more complicated man. The trauma has changed him. He sheds that layer of foolish goodness.

I know I’m projecting. But that’s the smokescreen between life and storytelling. It’s the reason I look for answers in a medium where I can make my own questions. At this moment, I want to reimagine the rift in the film as a forced separation. It helps me make sense of my own change. We never had a spat in our 20 years of friendship. So this phase — where I pick up the phone and remember that he isn’t speaking to me anymore — is the closest we’ve come to one. It’s too painful to acknowledge that Colm is actually around and cutting off ties with Padraic; I’d rather believe he’s gone. I’d also rather be in denial and visualise my friend around, and create our own little world of drama and disagreements. My dreams lately have starred him in various situations; I try to sleep longer to expand the feeling of his company. In the most surreal of them, he is by my side even as a stranger offers condolences for my loss. He is gone but he is there. He is watching me while I ponder over the prospect of missing him.

It brings to mind our shared love for a Scrubs episode starring Brendan Fraser. It’s called “My Screw Up,” and in it, the caustic Dr Cox (John C McGinley) is handling the treatment of his brother-in-law and best friend, Ben (Fraser). Cox isn’t worried about Ben’s relapse; the two spend the days joking around and bantering in the corridors of the hospital. It’s the only time we see Cox truly genuine and joyful in the presence of someone. However, the climax reveals that Ben is a figment of Cox’s imagination — and the children’s party Cox plans to attend on the weekend is none other than Ben’s funeral. Ben died in the hospital. And Cox’s processing of the trauma makes for one of the most poignant instances of ‘sitcom’ television.

I suppose the element that stands out is not the The Sixth Sense-style twist so much as the emotional subterfuge. Cox is upset with protagonist JD (Zach Braff) throughout the episode, because an old patient seemingly dies under his watch. It’s Ben who playfully convinces Cox to forgive JD, and to embrace that it wasn’t the younger doctor’s fault. Later we discover that the patient who died was Ben himself — Cox was only blaming JD to make sense of his best friend’s passing. In the end, Cox is too tired to fight the reality of the funeral anymore. He snaps out of it; all his colleagues, including JD, stand by his side. He is a broken man, but also a better one. The sight of Ben virtually guiding Cox through his grief — urging him to make peace with JD; to stop being angry; to be the bigger person — is something I’m starting to fathom. This is the progression of grief I’m learning to embrace. I may have mutated into a bitter Padraic for a month, but I can now sense the calm after the storm.

Those dreams I’ve been having about him aren’t disorienting. They convey the essence of the Scrubs episode — his favourite episode — in which, despite being gone, one friend pushes another to see the light. One friend’s parting gift to another is the humility to bleed and be human. Cox is heartbroken but not deluded. Subconsciously, this is how he always saw Ben: positive, spirited and an enabler of wisdom. Lately, every time I lose my patience, I think of how my (late) friend might react. I feel him gently urging me to accept people for who they are. And to be modest about my little triumphs. He practiced equanimity in his everyday life, and it’s this equanimity that I hope to make my parachute. My first instinct now is to check my instincts — of judging, ranting or being disappointed — because he’s still around. If a nihilist like Dr Cox went from caustic to vulnerable, there’s no reason I cannot.

As a result, I now feel like an internal self-help book. I don’t feel like dwelling on a setback at work. I don’t feel like being opinionated on social media anymore. I don’t feel like blaming others for being caught up in their own lives. I find myself looking at two sides of every situation. The friend who called me ungrateful at my lowest moment — I can see where he came from. I get that he was in a bad space himself. Perhaps his own grief and trauma got sick of being subsumed by mine. But I’ll always appreciate the fact that he was with me when we received the news. I send happy emoticons on WhatsApp groups I was earlier passive-aggressive in. I don’t snap if someone cancels a plan. I dilute my sense of entitlement and expectations. I thank anyone who takes the time out to text or check on me. Some of them are his friends who share their experiences and feelings, which never ceases to move me, because it feels like he’s still creating bonds after he’s gone. I’m speaking with more people, too, inspired by his ability to sustain friendships — big, small, casual, serious — across the globe. I’m not being pretend-nice either; it’s just that my Ben has convinced me to stop being petty and widen my horizons. To be grateful for whoever and whatever I have. To trust in myself and my capacity to improve.

Most of all, I’ve stopped escaping the void. After his funeral, I travelled to new cities for three consecutive weekends. I didn’t want to face myself in my bedroom. I was seeking solace in places and friends who felt differently than I did. I was looking for a release in a strange and distant scenery, because that’s what movies had taught me to do. I thought I could run away, forge perspective out of thin air, and return as an enlightened man. Ultimately, however, it took me one reality check to realise that home is my only healing. Family — my mother’s care, my partner’s empathy, my father’s phone calls — is my only constant. I wonder why I didn’t see it earlier. When I returned, battered and bruised from all the flights and the sleepless nights in other beds, it just felt right. All those displacements felt like ancient history. It’s a fitting tribute to him, because his family was his top priority, especially in his final months. His beaming smile in family photographs is the epitome of gratitude. I do feel a little kinder, a little at ease with the fictions of humanity. The edginess is almost gone. The angst has melted. He’d approve of my epiphany, but he’d also chuckle at the irony that he had to depart for me to grow a more balanced brain.

So I will retire to a quaint hilltown with my partner. We will spend the days reading, cooking and taking long walks around our cottage. But we won’t be alone in this town. My best friend — someone I miss a lot; someone I’ve seen the world with — lives a few doors down. We meet at the local bar for two beers every evening. We play cards. We listen to music. We reminisce about our families and late parents. We laugh about the time I burnt down his cottage because he stopped speaking to me. We joke about the eulogy I gave at his funeral — a funeral I had programmed myself to believe was a birthday party — all those decades ago. Then I go back home, tipsy and satisfied with the surety of our bond. Come hell or high water, this one hour at the bar is non-negotiable. I’ve earned the muscle memory of this grief; I’ve lived long enough to reframe memory as the medicine of familiarity. It doesn’t need a text message or a phone call. It’s like strolling into the same basement pub in a faraway country without even planning it.