Parasakthi: The Revolution Has A Face, Not A Character

Sudha Kongara gives her revolutionary a powerful outline — but withholds a complete shape, choosing symbolism and safety over political complication.

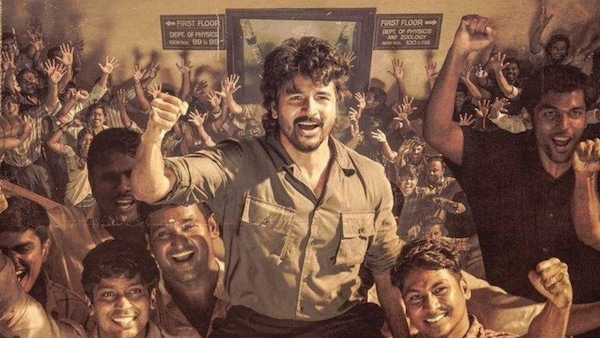

Promo poster for Parasakthi.

Last Updated: 03.19 PM, Jan 11, 2026

IN Parasakthi — the 2026 version, not the seminal 1952 Krishnan-Panju film written by M Karunanidhi — Sudha Kongara often films Sivakarthikeyan in silhouettes. We meet Chezhiyan (helpfully working as a Tamizh name as well as a call to a revolutionary like Che) in 1959, and what we first see is his outline amidst darkness as he holds an effigy (the language of Hindi anthropomorphised) and threatens to stop a train. It is an immersive entry for a hero in a film based on the anti-Hindi agitations of 1965 in the Madras state. We see him as a student leader, an activist and a revolutionary. And the silhouette gives him shape and form, but not characteristics. It centres the movement and students as its ultimate progenitors.

But as far as Kongara’s screenplay (co-written with Arjun Nadesan) is concerned, it also restricts giving Chezhiyan something whole. Chezhiyan’s friend dies in the train fire, and almost in an instant, he gives it all up and puts an end to the Purananooru Squad (named after the Sangam anthology of poems that translates to four hundred poems in the puram genre), a shadow group of student leaders. We get the mechanics of this. We can see that the film wants us to briefly disengage with him and focus on the larger politics outside, and it will make for great dramatic tension if fate forces Chezhiyan back into his activism. That’s largely what happens in Parasakthi. We segue to 1964 to learn about his younger brother, Chinnadurai (Atharvaa), another loose cannon of an activist who is unaware of his elder brother’s past, and a brief romantic sidetrack with Ratnamala, played by Sreeleela. The expected narrative trampoline act transpires just before the intermission. Once again, we see Chezhiyan in silhouette, this time in broad daylight and therefore against the blinding rays of the sun (make of that image what you will!).

The predictability is not the problem. We could perfectly imagine the whole film if we knew even the basic facts of the 1965 anti-Hindi agitations. It’s mainstream cinema’s compulsions that seem to dilute Parasakthi from what it could have been. After the spirited opening sequence, the story travels and stays in Madurai, where Chezhiyan works in the railways and lives with his grandmother. Ratnamala, their Telugu neighbour, is also part of Chinnadurai’s student politics and Chezhiyan today is a pale reflection of the man that he once was. He looks the other way from all irritation, asks Chinnadurai to only focus on education and even extracts a promise from his brother that he won’t go about setting fire to things. What's more, he is even ready to learn Hindi almost unflinchingly while always repeating that it’s Hindi imposition that Tamil people are against and not Hindi.

Parasakthi is a film that doesn’t want to be messy; it wants to be that front bencher who is always trying to impress the teachers. It wants to be inclusive while being fictitious, co-opt all other language protests and display a more perfectly united face. It wants to insert a needless romance track that will seemingly appeal to the masses, studios and producers. It won’t make sense in the film and will remain inconsequential. But the film will play along. The sequence before the intermission, when students protest the Chief Minister’s inauguration of the Hindi week, is when things heat up again. We get why Chezhiyan will rise again, but if he was really an intelligent student as everyone claims, wouldn’t he have seen this coming? That thought swims in our heads throughout the film’s first half, all the way till the pre-interval sequence. Even here, the action leaves much to be desired. Kongara cuts quickly, the crowd shots are almost blink and miss, and even though the majestic presence of Chezhiyan ramps up the temperature, he doesn’t get a standout set piece.

It takes well into the second half for Parasakthi to learn the art of foreplay. What lacked uniform rhythm in the first half gets some sustained build-up towards action as we go from custodial torture to a Delhi episode in the middle of the road with Indira Gandhi (a bit of anachronism to up the stakes as Lal Bahadur Shastri was Prime Minister in 1965) to a climax that moves from Pollachi to Coimbatore in a train. The action is more streamlined here; we learn about the large wingspan of the Purananooru Squad, the Delhi episode, even if corny, works for its theatrical staging, and some of the quieter bits with other student leaders (the cameos are fun) and Kaali Venkat are fun.

The train in the opening sequence also had Thiru (Ravi Mohan), a menacing state actor who's also KGB-trained and harbours fresh hatred for Tamil and every Tamizhan agitating against Hindi. He takes it upon himself to put an end to the menace, and Mohan is the surprise of Parasakthi. He is a man of action, one who wouldn’t flinch from adopting the violent methods that the British incorporated just over two decades before the events in this film. Mohan here is unlike any role he’s been in, sufficiently contorting his face at the Tamil language, permanently agitated at all that stands for it. Sivakarthikeyan, after a lacklustre Madharaasi, finds half a part in Chezhiyan and sinks his teeth into it. The results are mostly to his credit.

This is a curious film. It wants to piggyback on its title (its original title, Purananooru, would have made a great one!), recalling a past work that the leaders of the Dravidian movement expressly created to propagate their progressive ideology. But it also wants to be the mainstream commercial Tamil film with its share of romantic track, songs and a melodramatic bone that turns towards personal tragedy for motivation. It has some tiny deft touches. Like the brothers pilfering the lighter from each other with arson as their preferred mode of agitation. Or Ratna’s stuttering in front of the radio mic giving way to a most graceful address in the end. A railway engine blowback becomes a Chekhov’s gun with two trains bookending the film itself. But like Chezhiyan’s characterisation, they don’t all amount to a satisfying whole.