Staging Desire: Queer Cinema, Fragile Spaces, & The Hope Of Visibility

From pop-up screenings to Kashish Pride Film Festival, queer cinema made space for desire and defiance — but still faced silences where it most sought to be seen. Vikram Phukan writes.

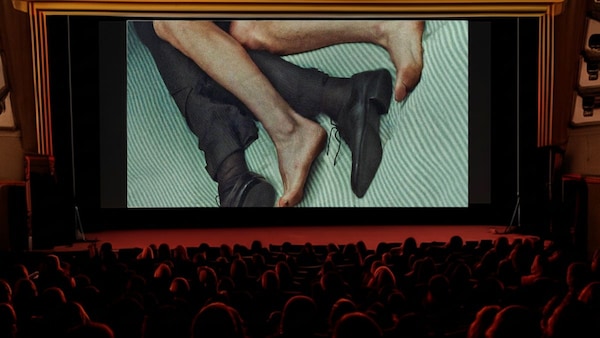

Tender, defiant, and sometimes unseen—queer films this Pride reminded us that visibility isn’t arrival | Representational Image.

Last Updated: 05.02 AM, Jun 30, 2025

THIS PRIDE MONTH, a flurry of queer film screenings unfolded across Indian cities via a smattering of pop-up festivals. At unexpected venues — living rooms, plush salons, gallery spaces — the programming ranged from Badnaam Basti (1971), the little-seen film with a ‘found queer’ subplot; to Joyland (2022), the tender, subversive Pakistani drama with a devastating denouement; to Bomgay (1996), eternally dubbed ‘India’s first gay film’. There were risqué shorts from the Kinky Collective, and even The Children’s Hour (1961), where Audrey Hepburn and Shirley Maclaine famously didn’t realise they were playing women in the throes of conflicted love. The diversity was thrilling, the settings intimate but also precarious. Yet, amid this sprawl of screenings, Mumbai’s Kashish Pride Film Festival remains the country’s preeminent queer cinema event, proudly citing its 150-odd films from nearly 50 countries. That number included a Palestinian film that ultimately didn’t receive screening clearance — a quiet reminder that for all the celebration, queer cinema still encounters invisible borders, especially when it brushes against the sensitivities of the state.

This year, Kashish moved from the period elegance of Liberty Cinema’s art deco interiors to a suburban multiplex, a space with far less character. But once its queer denizens arrived, with their mix of reserve and flamboyance, the place began to take on a different mood. Even so, the shift wasn’t immediate; it was only the weekend screenings that drew larger crowds. That’s why Luca Guadagnino’s Queer (2024), dubbed the ‘opening film’ of the festival on a Thursday, began on a subdued note, with a turnout thinner than the occasion deserved. The film, though, more than made up for the muted energy in the hall. Its moodiness and depth of palette came alive with sheer vibrancy on the big screen, where it belonged. For those who’d watched it earlier on MUBI, the difference was palpable, not least because they were watching it in assembly, within a queer community space, as Kashish inevitably transforms any cinema hall into, regardless of its provenance.

With an opening act set in 1950s Mexico City, Queer is wonderfully atmospheric; one could feel the sultry heat in the folds of the costumes, the way they clung to actors’ bodies, and the way their hair was tousled under the tropical humidity. With locales that engulf the characters like living, breathing postcards, Guadagnino evoked a sense of visual lyricism and fraught sensuality reminiscent of Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice (1971). And Daniel Craig’s William Lee, a tequila-swilling, heroin-addicted American expat, appears in crisp, pale tones that echo, in no small measure, his great predecessor Dirk Bogarde’s fragile, yearning elegance in the Visconti classic, while tracing a similarly slow, unravelling descent.

But in Queer, the fixation on unattainable desire is not a death sentence. It unfolds into something more layered. Though a period film, the film refreshingly avoids the usual archetypes of doomed repression or redemptive awakening. Eugene Allerton, a young drifter played with remarkable restraint by Drew Starkey, is handsome, watchful, and emotionally hard to read, never fully disarmed or defined by the queerness others try to ascribe to him. There’s no unspoken ache that quietly extracts its toll, as in Brokeback Mountain (2004). Instead, what emerges is a kind of calibrated aloofness, without a trace of cynicism. When he gives in to a drug-induced night in Colombia that devastates and liberates, his guardedness remains. What he chooses to reveal, and when, feels like its own form of agency.

By contrast, Lee is impulsive, needy, and driven by a hunger for the much younger Allerton, a desire that barely masks itself. But his neediness and lack of gravitas (even in the impossibly charismatic Craig) aren’t just about age; it’s about choosing volatility without apology. His self-destruction and drug use aren’t pathologised; the film lets him be without judgement. His self-loathing surfaces as disdain for “those queers,” the furtively flamboyant clientele of a secret gay club. It’s a judgement the film neither corrects nor condemns. Queer resists imposing a moral framework on its characters and this detachment becomes all the more compelling because neither Starkey nor Craig overplay. Their performances are muted and precise, allowing us to glimpse the emotional truth of people behaving, withdrawing, reaching out in fumbling, inconsistent ways.

The film registers queerness in its everyday textures — the unspoken claims, shifting dynamics, and momentary frictions that shape intimacy. It allows queerness to appear messy and lived, where desire, beauty, and power remain in flux. Allerton trades on his beauty, but this isn’t as much a fall from grace as simply survival. And through it all, there is Craig: craving, hallucinating, undone by longing. The meta-text is unmistakable, especially when he staggers on to the beach in a direct nod to Casino Royale (2006). But this time, he’s not in command. He’s exposed and vulnerable, and the film doesn’t flinch. Such textured, ambiguous portrayals are now almost de rigueur at Kashish, which still features its share of affirmative, coming-into-the-light stories, but can also venture into darker, more unresolved emotional terrain.

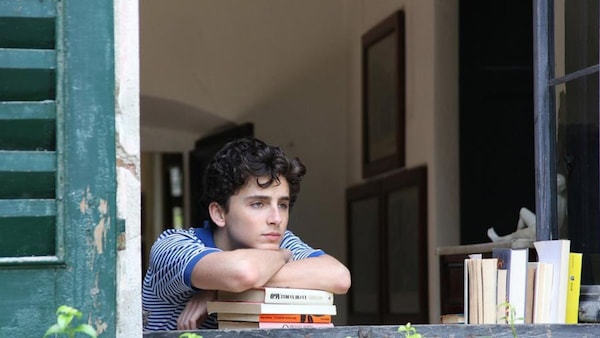

Still, despite being a masterwork in its own right, Queer’s modest outing at Kashish hinted at a deeper truth: queer film festivals, especially in India, don’t necessarily draw in the wider cinema-loving public — not even when the films are this accomplished. Not in the way that a film like Guadagnino’s own contemporary classic Call Me by Your Name (2017), equally unabashed in its queerness, was all the rage when it was screened at the resolutely mainstream MAMI Film Festival years ago. That was a sun-dappled bildungsroman (anchored by Timothée Chalamet’s revelatory performance as Elio, a boy on the cusp of adulthood), while Queer is a starker meditation on longing and self-destruction — which might partly explain the difference in receipts.

In Postcards from Colaba, a promenade production conceived by this writer and performed along a culturally resonant trail through Colaba, there is a scene outside Regal Cinema, where three fictional characters reminisce about a surprise encounter with Call Me by Your Name during its MAMI screening at the very same venue. The hall had been packed to the rafters, with barely any standing room, for a film that none of them had heard much about. It unfolded slowly, delicately, revealing itself as a gay love story, and in that slow emergence was a kind of grace. What began as an unremarkable afternoon screening became, for these characters, quietly transformative. Even the purportedly straight audiences around them seemed to give the film its due: not with overt enthusiasm, but with a kind of respectful attentiveness. In that darkened hall, their own lives, emotions, and private selves felt not just reflected but momentarily dignified, permitted to exist without explanation or apology. At one point, they even vie for Chalamet’s attention — a shared fantasy, of course. It’s a moment of levity that only makes the memory feel more communal and real. It’s exactly the kind of feeling Kashish strives to evoke, and often does, for its audiences each year. In Postcards…, these characters speak lines pieced together from real memories, overheard confessions, and private reflections, all fragments of queer viewership that theatre, like cinema, sometimes allows us to hold in the open.

And yet, as those overlapping memories suggest, there’s a question that queer film programming in India must still reckon with: should the aim be to place queer films on mainstream platforms, or to bring mainstream audiences into queer spaces? The two goals aren’t mutually exclusive, but they remain unequally realised. What happened at Regal during MAMI was memorable, but also accidental. Kashish, by contrast, builds its queers-first space with care and consistency, year after year. The trouble is, the onus still falls on queer cinema to make itself visible.

Later in the play, the scene folds back into another festival-programming coup from 2015, when the prestigious opening film for MAMI at Regal, was Aligarh (2015), Hansal Mehta’s searing portrait of a discreet professor outed through a sting operation and publicly shamed. That Aligarh could open a mainstream festival nearly a decade ago, while Kashish still struggles to access certain premieres, is telling. In recent years, though, it has managed notable exceptions — Badhaai Do (2022), for instance, albeit screened after its theatrical run. This year brought both Elliot Page’s Close to You (2023) and, of course, Queer. Still, there’s an irony in the fact that a coveted title like Rohan Kanawade’s Sundance-feted Sabar Bonda (2025) did not screen at Kashish pending its national premiere, even though Kashish was the platform where Kanawade’s early shorts first found an audience. Of course, for independent queer films, a mainstream berth can offer reach and visibility that even the most loyal queer festivals can’t always match. There is always a trade-off between community and exposure, affirmation and acclaim.

In the end, queer festivals like Kashish do more than screen films. Not every title makes its way here, and not every audience shows up. But when they do, something shifts; even as a film simply finds the room to breathe. These festivals honour the past while holding space for what’s still emerging. As a case in point, just around the corner from Regal stood the first film office of Merchant Ivory Productions. James Ivory and Ismail Merchant, who created the longest-running film collaboration in cinema history, were also life partners, a fact that remained largely unspoken in public discourse. Years later, Ivory would become the oldest person ever to win a competitive Oscar, for his adapted screenplay for Call Me by Your Name, a film that, like his and Merchant’s Maurice (1987) from decades earlier, dared to take queer desire seriously. At the ceremony, Ivory wore a shirt printed with an image of Chalamet as Elio — a quiet, personal flourish that seemed to carry a world of meaning. Directors like Guadagnino, whose films have graced both Kashish and MAMI, remind us that queer cinema is no longer confined to one world or the other. The most luminous works often move between spaces. They find intimacy in queer festivals, and visibility in the mainstream. This does not dilute their charge, but deepens it.