Signalling the Shift: Decoding a Front-Page Salaam to Superstar Rajinikanth

Smruti Koppikar on when, and why, the revered front page as celebration is welcome.

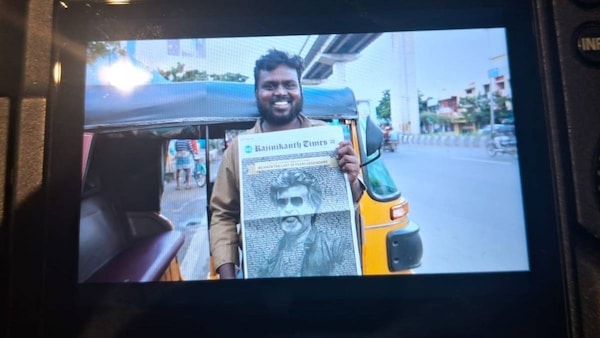

A Rajinikanth fan in Chennai is snapped with the 19 November 2025 edition of Hindustan Times.

Last Updated: 08.08 PM, Dec 12, 2025

EDITOR’S NOTE: As superstar Rajinikanth turns 75 today, it felt like the right moment to revisit a cultural gesture that unfolded just weeks ago — one that has continued to spark conversation inside and outside the media world.

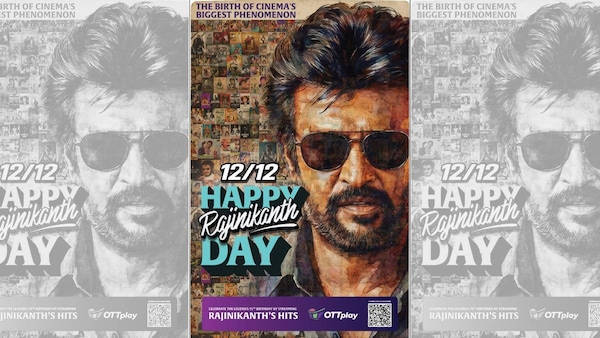

On 19 November 2025, Hindustan Times, in partnership with OTTplay, reimagined its front page as Rajinikanth Times, a one-day tribute marking the actor’s 50 years in cinema. The takeover went beyond a branded moment; it was a rare instance of a legacy masthead bending, briefly, to honour a cultural force whose influence transcends geography, language and genre.

To understand what such a gesture signifies today — in an era of personalised feeds, algorithmic newsflows and vanishing print rituals — we invited media scholars to examine its deeper meaning.

In the essay that follows, journalist and editor Smruti Koppikar examines the front page as a site of power, ethics and myth-making.

Also read the companion column to this op-ed: Who Owns the Front Page? Rajinikanth & the Power of Tribute in Modern Media.

***

THE CODE WAS ALWAYS CLEAR. The front page of a newspaper was the most prized of the real estate always sought after in newsrooms by reporters with their stories and editors with their headlines. To the outside world, the front page communicated many things all at once – a unique selection of news stories, the editorial policy of the newspaper that guided the selection, the importance of stories in a hierarchy, the news organisation’s approach to using different elements such as data and visuals besides text, and the signal to not only its readers but to society at large of what the newspaper considered significant and relevant that morning. The front page was the newspaper’s showcase, a place of self-assertion and identity.

That was when news television was another world, digital news had yet to make its debut, and social media was a mere idea. Since then, everyone and his uncle has written the obituary of the newspaper. But in the transformed multimedia universe, neither has the value of the printed newspaper shrunk nor the import of its front page. Younger readers may not buy a copy of the newspaper but this does not diminish all that the front page stands for – they simply see it on their devices. Decades ago, small parcels of this real estate began to be hawked to the highest bidder among advertisers and the sanctity of the front page was proportionately dented. News was shape-shifted for commerce. As neoliberal economics and consumerism expanded their footprint, full-page advertisements crowded out the front page in many Indian newspapers; it was effectively Page 5 or 7.

Turning the front page of Hindustan Times into ‘Rajinikanth Times’ to hail one of the biggest superstars and icons of India’s film industry on his remarkable and sociologically-stirring 50-year journey signals another shift – from advertisements to acclaim, from commerce to celebration. It’s a stunning page with several elements layered into the image, from names of Rajinikanth’s films to the awards he has won along his journey, his unmistakable visage in grey relief against the black background, some of the text mysteriously subsumed into his jacket. A definitive portrait in close-up but not too intimate either. For Rajini’s fans — or the Thalaivar cosmos, as it were — the front page is one for the family treasure box, to be stored and cherished, to return to and share with grandchildren someday. It is, to borrow a descriptor from the page, legendary as front page non-paid tributes go.

Rajinikanth is not a mere cinema superstar; he is a one-man cultural industry owning swag and the rags-to-riches story like few actors have, spawning fan and fan clubs that call themselves ‘fanatiks’, somehow merging the on-screen dialectics of angry rebel and romantic hero in ways that Hindi films stars have not, staying away from the filmy glam and glitz but watching every release of his turn into a calendar event, seeing temples built in his honour and his real-life legend travel far and wide across linguistic and geographical borders. Why, it has even traversed the age barrier. Generation gap empties out of its meaning when it comes to the Thalaivar cosmos. Even the digitally-reared and social media-influenced young lap up Rajinikanth memorabilia. The ‘Rajinikanth Times’ front page is that. It breaks the classic front page mould to perpetuate his long-running myth.

But Rajinikanth did not need the specially-crafted front page of the country’s second largest or second most-read newspaper; Hindustan Times did itself and its readers a good turn — an indulgence, even — in choosing to devote it to the Thalaivar. It’s public acknowledgement that the man, who went from bus conductor Shivajirao Gaikwad to the Thalaivar in the movies of south India before bringing his signature swag to the Hindi screen, matters beyond all commerce and deserves to occupy the prized real estate that the front page is.

Encoded in this is the French essayist, literary critic, and philosopher Roland Barthes’ famous postulations, also the title of one of his essays: ‘the death of the author” which suggests that the creator is ‘dead’ after the creation. The front page of ‘Rajinikanth Times’ now belongs to the icon and his cultural cosmos, not to the Hindustan Times or OTTplay that are its creators. If we ask whether the gesture of turning over its front page to Rajinikanth will make Rajini fans revere the newspaper more, the question would be misplaced. It will make them revere their Thalaivar a few notches more that a ‘northie newspaper’ like Hindustan Times crafted the valued front page around his cult-like status. The encoding-decoding, the basis of cultural studies, is complete.

In this figurative doffing of the hat, twirled and flipped like Rajini does his guns, in this salaam to a deity, the newspaper exemplified the process of myth-making. The media, to use Barthes’ lens again, does not merely reflect reality but actively shapes people’s understanding of it, and, in the process, helps create or deepen powerful myths in popular culture. In the case of this front page, both the literal and direct meaning (denotation for Barthes) and the cultural or ideological meaning (connotation, according to Barthes) are constructed which add a swig or two to the timeless myth of Rajinikanth. The signification is clear; the newspaper is happy to take part in the myth-making (or myth-deepening) process.

It's known that the media creates meanings all the time, even unintentionally. The very act of making news, selecting some and discarding others based on a broad understanding of what is significant to the dominant society and what would pass internally, is the construction of meaning. Jean Baudrillard termed it as the “simulation of reality” in his work Simulacra and Simulation where he argued that contemporary society has replaced reality and its meaning with signs and symbols that construct the perceived reality. First, Rajinikanth simulated reality on screen, even bent reality with his fantastical reel prowess, then the media constructed another layer atop it into his persona. The ‘Rajinikanth Times’ is a part of this on-going process.

The occasion of the superstar’s 50 years in cinema is incidental. The tribute could have been like any other special in a newspaper — a few inside pages of text and visuals that traced his unbelievable life and stardom — but it was the front page. The front page is an outcome of complicated processes within a news organisation, many external and a few internal, signifying to the readers the most important news stories of the day. To leave the news aside and to eschew advertising in order to create ‘Rajinikanth Times’ meant neither the editor nor the business head was happy. Perhaps, the marketing and design chiefs were.

To fiddle around with the front page this way would have mattered a great deal till the 1990s when the commercialisation of news was yet to go full throttle, or even till the mid-2000s when the algorithm-driven platformisation of news had not taken hold. In the hyper-digital platformised media ecosystem of today, the front page presumably does not carry the same gravitas. Wrong. The value of the front page is no less than it used to be; may be marginally fewer people see it but its integrity is no less. It continues to be closely tied to the newspaper’s ability to show spine on issues, to hold power accountable. Front page headlines still matter – even the social media handles run on them – in fact, headlines have become a comment when comment as dissent have no longer found space in newspapers.

In the propagandised media, when newspapers baulk at the suggestion of front-paging corruption stories of governments and shy away from asking difficult questions of those in power, the front page can easily turn into an unpaid advertisement for the nation’s ‘power elite’ — the select few with awesome political, economic and social power, to borrow a phrase from Herman-Chomsky’s ‘Manufacturing Consent’. Large sections of the mainstream media, including the once-revered “quality press” or the “legacy media” that Hindustan Times belongs to, have become propaganda sheets for the powerful. In such a media environment, the front page celebrating a film star is less pretentious and considerably more honest that the run-of-the-mill one with ‘news’ or advertisements.

We need courageous journalism on the front page, more than ever. If that cannot be, then distraction like ‘Rajinikanth Times’ is preferable to propaganda on the front page. This went down well because it was a one-off; repeated often, it could lose its charm. The medium is, to invoke Marshall McLuhan, the message after all.

Smruti Koppikar, a Mumbai-based journalist, editor, and urban chronicler, is presently Founder-Editor of Question of Cities, India’s only online journal dedicated to cities, ecology and social equity. An editorial consultant and columnist on urban issues, she spent more than three decades in some of the leading newsrooms in Indian in a gamut of roles from reporting to editing, including as Senior Editor of Hindustan Times in Mumbai. She teaches journalism, multimedia fundamentals, and gender.

(Disclaimer: The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of OTTplay. The author is solely responsible for any claims arising out of the content of this column.)