Sinners: Ryan Coogler Summons The Cinema Gods

Coogler compresses centuries' worth of the Black experience into a beautifully pulpy and poignant 137-minute motion picture about one wild night at a barrelhouse, bloodthirsty vampires — and music.

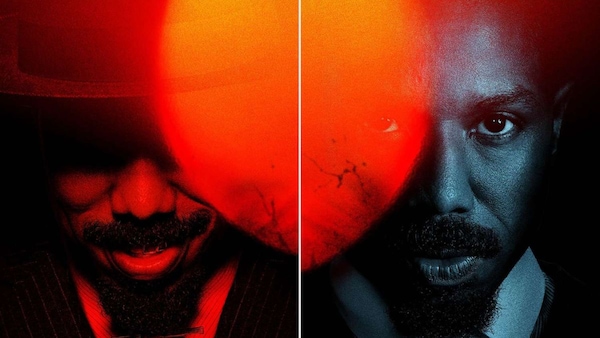

Promo poster for Sinners.

Last Updated: 11.10 AM, Apr 21, 2025

SINNERS stars Michael B Jordan as identical Black twins Smoke and Stack, who return to their hometown in 1930s Mississippi. It’s been 7 years, and their loaded backstory — a troubled childhood with a violent father; a World War I stint and plenty of PTSD; a brief return only to have their lives upended by tragedy; an escape to big city Chicago and an entry into the Al Capone gangster universe — bleeds into this film. None of it is shown, but every moment bristles with the unresolved baggage of history. Smoke’s reunion with his estranged wife, and occult ritualist Annie. Stack’s reunion with his white ex-girlfriend Mary. The brothers using their Chicago “blood money” to buy an abandoned sawmill from a former Klansman; their ‘recruitment’ of old friends to turn the sawmill into a rocking juke joint. A fleeting argument where Stack accuses Smoke of letting Annie “again” come between the brothers.

This backstory has enough meat to be a living, breathing film of its own. An unseen prequel of sorts. But the past is reduced to a series of passing mentions and expository hints. This ties into the profound core of Sinners: the invisible tangibility of a culture — and its edited influence on the archives of American living. Writer-director Ryan Coogler somehow compresses centuries' worth of the Black experience into a beautifully pulpy and poignant 137-minute motion picture about one wild night at a barrelhouse, bloodthirsty vampires, and most of all, music.

The lore of Sinners goes thus: great music has the power to rupture the space between life and death, but it also attracts the danger of those who want to usurp it. That gifted character in the film is the twins’ young cousin, Sammie (Miles Caton), an aspiring musician hired to perform on the opening night of the joint. His talent is so transcendental that — in perhaps the most spellbinding instance of cinema as an act of feeling and resistance — it stirs the spirits of the past and the future. This scene sounds so unfilmable that to see it is to believe in the immortal sanctity of art.

But Sammie’s genius is also so pure and mythical that it attracts the attention of three very white vampires: a Twilight-coded Irish-American immigrant and two crony Klansmen. Once all hell breaks loose, the twins and their motley gang set out to protect — to preserve — Sammie. The stakes are staged so ingeniously by Coogler’s genre poem that it projects a fight to preserve a people, not a person. Sammie’s fate comes to represent something far less generic than the continuity of humankind in a zombie survival thriller. If he dies (or worse, puts down that guitar), the voice of an entire culture dies. The future of the blues — soulful race music signifying the resilience and depth of African-American identity — faces extinction; the past, too, will be erased.

It takes some doing to go beyond the conventions of a racial drama and expose the language of white microaggression through the rhapsody of one night, but Coogler does it like nobody else. He remains the most inventive, direct and quietly necessary storyteller of a generation whose moviegoers are too often confronted with revisions of history and fetishisations of truth. In his case, what you don’t see is what you get. Vampirism and the infecting of patrons become cheeky allegories for not only the suppression of Black identity but also long-term colonisation through pop-cultural and artistic imposition. One of the many symbolic moments features the Irish vampire belting out a traditional bonfire anthem while newly ‘bitten’ Black guests sway to his performance. The way they move exudes a kind of subconscious compliance that reflects a modern landscape, one where generations of native-American and coloured artists have had to conform to — and create within the confines of — mainstream systems. He targets Sammie because he wants to homologize his talent and make it accessible. It’s the story of America in a nutshell: white immigrants reach the top of the food chain and feign belonging by ‘adapting’ the ways and preying on the trauma of marginalised locals.

Which brings us to the tagline of the film: “We are all sinners”. It’s more than just the provocative gimmick of the lead star playing indistinguishable men (with distinguishable personalities); the tempo and transitions of the film feed our notions of casual racism by blurring our ability to tell one brother from the other. The complicity extends to our broader role as connoisseurs and consumers of storytelling. Cinephiles and empaths like us, we fawn over directors like Quentin Tarantino and Damien Chazelle and their impassioned redraftings of Black history (Django Unchained) and the democratisation of their music (Whiplash, La La Land). They’re visionaries in their own right, but the reason their vision is so employable is because it isn’t burdened by a sense of ownership and inheritance. At the end of the day, they’re still white men making movies for white people about their relationship with Black society. Their solidarity underlines their art.

At some point, however, it’s hard not to think of how the whitewashing of jazz in a film like La La Land might be the very vampirism and blood-sucking — the cultural gentrification — that Sinners alludes to. “Give me your words and songs,” the vampires repeat, hinting at an endless existence of co-opted art. Modern classics like Chazelle’s anti-fairytale are inadvertent symptoms of the bite inflicted by the ‘white travellers’; John Legend’s character (with his modified-jazz band), for instance, is more of a massacre survivor who goes populist on his own terms. Chazelle is one of my favourite contemporary directors (his freakishly pale skin is a coincidence), but there are inverted echoes of the famous La La Land ending in the mid-credits and post-credits sequences of Sinners: a couple walking into a blues club, a melancholic owner, a back-to-youth performance, a last glance at the door. In doing so, Ryan Coogler reclaims the context and agency of Black storytelling — of Black artistes owning the mortality and morality of Black art — from the simplified romanticism of the white gaze. Ironically, he does it through a film that has the narrative scale and ambition of Chazelle’s Babylon. Just as Babylon internalised the chaos of Hollywood’s silent-to-talkies transition in the 1920s, Sinners treads the holy line between the musicality of film and the cinema of music. Action sequences, conflicts and resolutions unfold with the sort of foot-tapping and chest-heaving rhythms that have more in common with the blues. The IMAX aspect ratios play a key role in the mythologisation of the juke-joint parts — the night plays out as if it’s being remembered and lived through at once: the gravity of a memory marries the nowness of a crisis.

It says something that the twins, as well as Sammie, become a surrogate for Coogler himself: he navigates an onslaught, returns to his roots and shoots on 65mm after making it big with franchise hits (“blood money”) like Black Panther and Creed. He’s both the juke-joint and the people who survived it. It also says something that Coogler’s stance on the appropriation of Black art isn’t absolute. He leaves room for reciprocation by collaborating, once again, with Swedish composer Ludwig Göransson for the film’s distinctly bluesy album. As if to imply that not all white folks are folk-vampires — they can be a student of the form rather than an inspired or predatory outsider. It’s kind of lyrical that, with his authentic score, Göransson remains in service to a community without ‘staking’ a claim through their heart. It’s the only way to sin: his work exudes Black tradition, creative freedom and the freedom of tradition. After all, pages can be torn and images distorted, but nothing is quite as supernatural as the heritage of sound.