The Boy And The Heron: Hayao Miyazaki Bows Out With A Tour De Force (And Not A Footnote)

A decade after The Wind Rises, the master animator arrives with The Boy and the Heron, a hallucinatory fable about closure, acceptance and legacy among other things.

Last Updated: 01.46 PM, May 11, 2024

A YOUNG BOY journeys into a magical realm where encounters with a talking heron, a wizardly great granduncle, flesh-eating parakeets and soul-eating pelicans challenge him to grapple with the trauma of losing his mother.

Thank all the kami, all the Totoros, all the river, forest and radish spirits, that Hayao Miyazaki reversed his decision to retire for the second time. A decade after The Wind Rises, the master animator arrives with The Boy and the Heron, a hallucinatory fable about closure, acceptance and legacy among other things. If this latest from Studio Ghibli did turn out to be his final film (though we sure hope not), it would be in so many ways a fitting one. Because it draws its power as always from the compassionate details and spellbinding rhythms of his hand-drawn animation. Because it possesses a certain calm and clarity which allows him to draw a direct line from his fixations to us, his mesmerised viewers. Because it embodies the idea of hard-won optimism settling over a potentially last testament, making it all the more poignant. Above all because it is not so much a panoramic rehash of his life’s work as a supreme refraction of the elements he has pencilled, coloured and honed over the years — while pointing the medium towards a bolder future.

Leave it to Miyazaki to bow out with a tour de force instead of a footnote. The opening sequence of his 12th feature grabs us and plunges us straight into the inferno of the Pacific War. To animate the chaos of the streets in Tokyo 1943, he departs from the softer, cuddlier style towards a rougher, grislier one. Awakened by loud sirens announcing an imminent attack, 11-year-old Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki in Japanese and Luca Padovan in English) races through a city engulfed in flames in search of his mother. As he shoves through paralysed crowds to reach the burning hospital where she is trapped, the people melt and warp out of shape like ghouls. Everything around him deforms, animating his helplessness and disorientation. It’s as if we are watching a child’s world fracture forever in a single moment, his belief in goodness shaken irreparably.

The emotional gravity of the sequence suggests an artist processing a formative memory from his own childhood. To tell the story of Mahito, Miyazaki draws from his own lived experiences as a child of WWII. Although the director didn’t lose his mother to the war, as his protagonist does, the film is charged with grief and deep regret over things left unsaid. Not long after his mother dies in the Tokyo firebombing, Mahito is forced to retreat to the countryside, where his father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura/ Christian Bale) runs an air munitions factory. Shoichi has gone on to marry his late wife’s younger sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura/Gemma Chan). If Mahito wasn’t already upset, being bullied at school makes it all the more difficult to adjust to the relocation. Reality makes way for fantasy when he meets a talking grey heron (Masaki Suda/Robert Pattinson) who convinces him that his mother is still alive. Is the bird-man a friend or foe? What is certain is he may not be what he seems.

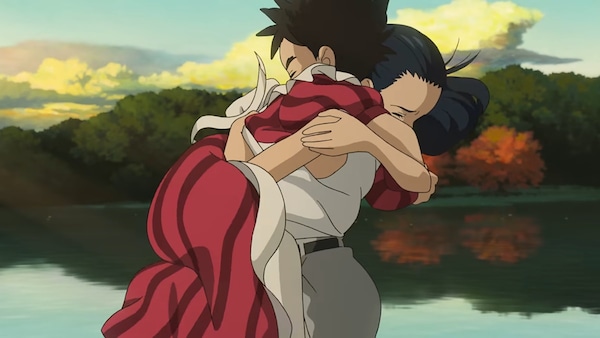

Dangling the carrot of a reunion, the heron lures Mahito into a dreamlike dimension that exists beyond time and space and shared between the living and the dead. On his journey, he encounters faces old and young: his great granduncle (Shohei Hino, Mark Hamill) who is the architect of a mysterious tower that acts as a portal to parallel realms; Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki/Florence Pugh), an old housekeeper who can assume multiple avatars; Lady Himi (Aimyon/Karen Fukuhara), a fire maiden who may be a younger version of his mother; and the warawara, unborn human souls who float to the surface to be born in the real world. Not all the warawara make it to their destination. For many, their journey is cut short by pelicans waiting to gobble them up as food. Such enchanting details and moments accumulate and lead to a devastating yet hopeful finale. Will Mahito stay in a fantasy world or accept the real world, pain, suffering, faults and all?

For Miyazaki, the power of animation comes from how the medium can be used as a springboard for visual poetry and a study in building character through a combination of action and stasis. We learn everything there is to know about Mahito, who he is, how he feels, what he fears and what he wishes, often from the world he navigates, a world carefully built by the director and his team. As with all his previous features, The Boy and the Heron too relies on Joe Hisaishi’s evocative soundscape to convey the inner journey of its young protagonist. A haunting but gorgeous piano motif serves as an emotional through line as Mahito accepts the peaks and troughs of growing up, moving on and all that they mean.

Which is why the original Japanese title of the film — Kimitachi wa dô ikiru ka (lit. How Do You Live?) — is more becoming. Miyazaki borrowed the title from Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel of the same name, a book which appears in the film as a gift to Mahito from his mother. Not only is the film shaped by the director’s childhood memories but also his love for said novel, in which an uncle teaches a teenage boy how to build a meaningful life. While watching the film, it is tempting to think of Mahito’s great grand-uncle as an analogue of Miyazaki, an artist who has spent his whole life animating stories about grief, pain and destruction, while urging us to not lose our childlike wonder, imagination and hope for a better tomorrow. We grow up, we grow old, but a part of our childhood never leaves us. It is to that part of us that Miyazaki makes a passionate plea for acceptance.