The Smashing Machine: Thriving Between A Rock & A Hard Place

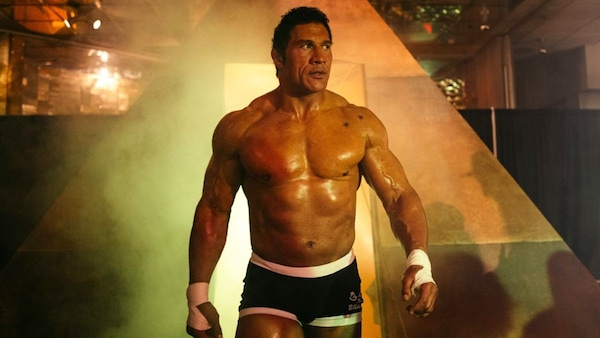

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson finally plays the role he was born to play — that of a champion wrestler and near-invincible strongman — only to challenge his stardom with a painfully human(e) performance.

Still from The Smashing Machine,

Last Updated: 02.22 PM, Oct 11, 2025

AS AN INDIAN CRITIC pummelled into submission by the hagiographic reverence and sanitised beats of homegrown biopics over the years, a film like The Smashing Machine is always a bit of a culture shock. What do you mean the hero is not really a hero? What do you mean he’s willing to be emotionally naked, broken, vulnerable, ugly, difficult and unreasonable on screen? What do you mean he’s a victim of his own decisions and not wronged by the world? What do you mean he’s not an inspirational story with a message? Benny Safdie’s sports biopic has a mixed-martial-arts protagonist who’s a serial winner with a drug addiction problem, a mansplaining habit, a toxic relationship that weakens him, a punctured comeback arc, and, eventually, he’s barely even the protagonist. It has Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson finally playing the role he was born to play — that of a champion wrestler and near-invincible strongman — only to challenge his stardom with a painfully human(e) performance.

Based on the life and career of MMA fighter Mark Kerr, The Smashing Machine takes some getting used to. It is defined by its confessional language. What’s fascinating is the paradoxical relationship between the subject and the storytelling. The Rock’s Kerr has the aura and physicality of a future legend, yet the film treats him as a striver and journeyman with everyday frailties. The camera shadows him inside the eye of the hype-storm, where it’s so still and ‘normal’ that he’s a self-styled underdog. You can never tell that he’s a big deal; that he’s an American pioneer of the sport; that he’s a monster in the ring who’s so intellectual and introspective with his words that it almost feels like a coping mechanism to justify the pain and abuse. The actor portrays Kerr as an imposter of sorts: his purism for his craft becomes a front for working-class desires. For all his self-help-coded reactions, his commitment wavers more than he’d like to admit. He’s a difficult partner, a bit of a narcissist, a hard athlete to manage, and a man who’s convinced that the onus is perpetually on him to be better. Some of the most striking moments feature Kerr breaking down like a baby once the performative veneer — the pressure of masculinity and mental fortitude — is dropped.

Speaking of veneers, the film only poses as a conventional sports biopic. Regular biopics package life in neat boxes of fiction, but this one uses fiction to keep hitting us with life. Every time it seems to be settling into a familiar rhythm, it teases our conditioning and eschews the excesses of the genre. Kerr’s return refuses to be “satisfying”; his relationship has no beginning or end; his fall, too, isn’t absolute. There are junctures when the following questions pop into our head: Will the girlfriend die? Will the best friend/coach die? Will Mark break his neck? There are shades of Rocky, Warrior (an imminent final between two ‘friends’ in a big tournament), The Wrestler and even Foxcatcher. But then the film stops short of being any of them, constantly reminding us that the truth of storytelling is different from the truth of living. Every trope is interrupted by a relapse of reality, as if to say: No, that’s not how it actually goes. No, it’s not so simple. No, it’s not so convenient. The anticlimactic nature is great — but only in hindsight; it’s difficult to process in the moment. It’s hard to engage with while it’s happening.

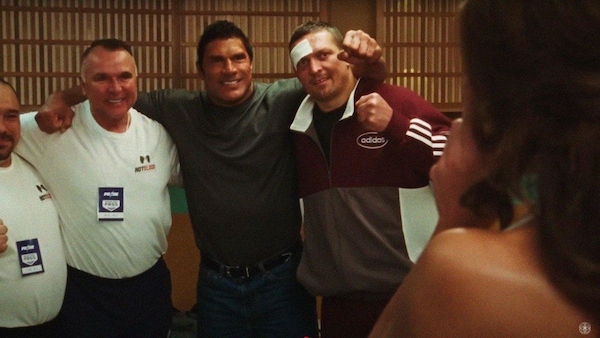

Given that we’re so wired to expect conflicts to be followed by resolutions, lows to be followed by highs, and sadness to be followed by redemption, certain aspects of the film sneak up on us. Like Kerr’s girlfriend and live-in partner, Dawn (a terrific Emily Blunt), who, for the most part, seems to be the one tolerating his main-character energy and addictive personality. We empathise with her when his team conspires to keep her away, or when he conveniently ignores her during fight weeks after enjoying her company in between. We feel for her when she travels to Japan for his matches, only to be stonewalled there. Similarly, Kerr’s friend-cum-manager Mark Coleman (Ryan Bader) remains by his side through thick and thin: on the periphery, worrying and working and hustling as Kerr’s biggest supporter. But then the film suddenly starts to see Dawn and Coleman as more than just supporting characters in someone else’s journey. We are reminded that they’re protagonists of parallel-running stories, ones we don’t notice because Kerr is so busy consuming the spotlight.

For instance, Dawn turns out to be the more complicated partner (“I miss when I could take care of him,” she tells her friend after he completes rehab and defies her control) and a troubled person. It dawns on us that we only saw her from Kerr’s perspective until this point — as a mercurial lover and an enabler — which isn’t a very curious or informed perspective. To the film’s credit, it ‘reveals’ her without antagonising her or sympathising with him. Around the same time, the camera begins to spot Coleman more than usual. We see more of his life: he un-retires and rises the ranks as a veteran fighter in his second innings, he wins against the odds, and he acquires the agency of someone more than a friend and onlooker in the background. He is essentially the family-holding older brother from Warrior or Foxcatcher, except he isn’t afforded the screentime of one.

By doing so, the film reflects the agonising almost-ness of Kerr’s stature. The others slowly go from concepts to humans jostling for narrative space: an eye-opener for a man who fought and moved like it was all about him. He cedes the limelight the same way he cedes immortality in a sport that keeps moving on from him. It’s as if he’s paying for not being able to look beyond himself and his struggles. It’s also as if Kerr is made to realise that he’s just another guy trying to figure it out; the camera was on him, but that didn’t mean he was more visible. The zoom-out aligns with the title of the anti-biopic, The Smashing Machine, a term that could’ve applied to either one of them. It also aligns with the fact that those like Mark Kerr didn’t exactly go into obscurity; they were stars who dared to reach for the ground. You remember him because his most fearsome opponent is his own story — a story that suggests it’s natural to forget him.