Trap: The Fraught Fatherhood Of M Night Shyamalan

This is #CineFile, where our critic Rahul Desai goes beyond the obvious takes, to dissect movies and shows that are in the news

Last Updated: 02.06 PM, Aug 04, 2024

THE TRAILER OF Trap is a neat social experiment. The hook is clear: A serial killer realises that the concert he’s attending with his teen daughter is a trap set to nab him. It’s an M Night Shyamalan film, so your first thought is: Surely, the trailer can’t have given everything away? Surely, there’s a Shyamalan twist ending. So watching Trap becomes a mind-game. As a long-time follower of the storyteller, you might conclude that the trailer was a smokescreen. Maybe the twist is that this man is actually not the serial killer; maybe the conceit is that he too wants to find the killer, which is why he looks so suspicious. Maybe he is the trap. Exciting. Then you watch the film through the lens of this theory, looking for signs and clues and red herrings. You see how far Shyamalan can stretch the illusion. You anticipate the revelation, but what you’re really doing is trying to win bragging rights. There are no words in the English language more satisfying to use than “I guessed it in the first 10 minutes”.

But the twist of Trap is that there is no twist. It really is just that — a cat-and-mouse game between a serial killer and his fate. So in a weird way, the director does win. You’re so busy expecting out-of-syllabus questions that you fumble the easy one. Or perhaps nobody wins. That’s the thing about Shyamalan today. His biggest trap is himself. He is such a prisoner to his own legacy that every subsequent movie feels like a parole hearing. Every original story becomes a battle with his past — and a war for newer identity. Trap, like last year’s Knock at the Cabin, is Shyamalan trying to convince us that he’s ‘reformed’. The result is nearly too simple: Look, no twist. Look, inner conflict and no cheap parlour tricks. Look, conventional suspense. Look, Josh Hartnett is acting badly on purpose because his character is pretending to be human.

Some old habits die hard. At some points, Trap seems to exist in the Unbreakable universe. The man, Cooper (Hartnett), feels like a descendent of The Horde (James McAvoy) from Split — a broad-daylight supervillain whose double-life and disparate personalities are manifestations of childhood trauma. The Philadelphia venue is shot and staged in a way that brings to mind David “The Overseer” Dunn (Bruce Willis) as a security guard at the concert in Unbreakable; one touch and he’d have visualised everything Cooper has done. The psychology of Trap, too, ties into the “they walk among us” and “the broken are the more evolved” vibe of the superhero trilogy. The camerawork is precise and methodical; some of the sound design (and door-banging) brings to mind the alien invasion from Signs.

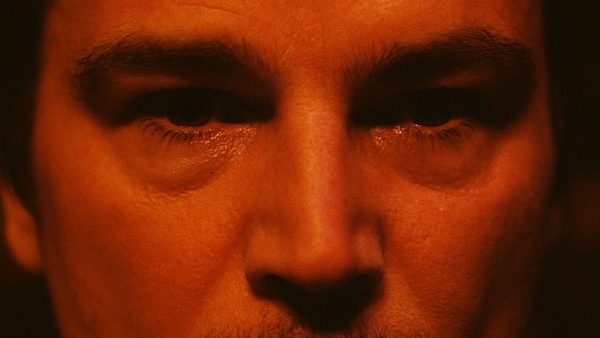

This is to suggest that Trap, in isolation, is not a mind-bending thriller. It’s consistently anti-climactic, especially when the story moves away from the concert hall. Some of the creative decisions — like the camera showing half of Cooper’s face to convey an alter-ego — are film-school gimmicks. But a slight shift in perspective can alter your viewing experience. Understanding where this movie comes from — not so much narratively as emotionally — makes it more rewarding. It’s not a stretch to say that Shyamalan’s filmography reflects his own journey as a father. If you peel back the layers of genre guile and craft, his movies are auto-fictional markers of this evolution.

Most of his early titles — The Sixth Sense, Unbreakable, Signs, Lady In The Water, The Village and The Happening — feature young parents grappling with their duties as nurturers and guardians. (The Village could even be seen as a portrait of stifling South Asian childcare). His next phase of titles like The Last Airbender, After Earth, The Visit, Split and Old feature an inevitable transfer of agency — those kids are growing up, defending themselves and saving the day. For Shyamalan, this is the cinema of letting go. Knock at the Cabin, where one dad ‘sacrifices’ another for the sake of his daughter, felt like a last hurrah — a final shot of paternal rage against the dying of light.

In that sense, Trap is Shyamalan’s most self-critical film. It’s as if he is now objective enough to step back and recognise his own flaws. It revolves around a man whose personal and professional lives ultimately collide — and explode. As odd as it sounds, the serial killer feels like a twisted surrogate for Shyamalan. At first, Cooper is arrogant and skillful at his ‘job’; he is a master of deception. Nobody has figured him out yet. He thinks he’s invincible, a trait that’s embodied by the entire film unfolding from his vantage point. Slowly but surely, this arrogance becomes his weakness. His aura begins to crumble; his family isn’t as oblivious as he imagined. The film spirals out of his control, transitioning from a father-daughter story (the names are a clue: Cooper, as in the famous dad from Interstellar; Riley, as in the famous daughter from Inside Out) to a killer-hostage drama to a marriage story. Each segment looks like a different movie, evoking Cooper’s ability to coldly compartmentalise different parts of his life.

It’s no coincidence that the pop-star is played by the director’s eldest daughter, singer-songwriter Saleka. She proves to be a surprising challenge for the seasoned killer. Which is fitting, because at some level, Trap is an ode to Shyamalan’s own family — and the modern generation — for teaching him a lesson or three. Cooper is undone by things that men of his intellect are conditioned to trivialise: Gen Z girls, social media, fan culture, mothers and the sixth sense of women. By putting a feisty brown girl and Asian boy in this fray, Shyamalan also manages to address another blind spot. As an Indian-American director, his movies have been rooted in his desire to belong: the characters and families are almost always American, and despite the spirituality of his storytelling, his film-making itself is ‘Western’. In fact, his signature cameos often frame first-generation immigrants as mysterious and murky people.

But Trap reclaims some of that cultural physicality. And it’s not performative. The ethnic elements of the film feel organic to the America it arraigns. Cooper’s subtle racism is Shyamalan owning up to his complicity and atoning for his colour blindness. (A Black fan of the killer even survives his own comic-relief arc.) Cooper struggling to thwart the ‘kids’ is M Night Shyamalan admitting that he isn’t unbreakable; he’s matured into glass, flitting between reflections and brittleness. For him, this is the cinema of moving on. It doesn’t fully add up, but confessions tend to be clunky. The truth tends to be plain. After all, how many South Asian parents swallow their ego and say sorry?