Wuthering Heights: The Most Expensive Instagram Story In The World

Think The Great Gatsby and Romeo+Juliet had a radioactive offspring who learnt about the birds and the bees by rereading 50 Shades of Grey in a crusty basement library.

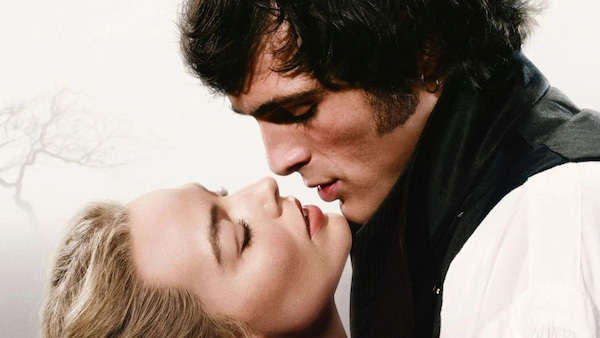

Promo poster for Wuthering Heights

Last Updated: 06.27 PM, Feb 12, 2026

OUR RELATIONSHIP with literature — especially the classics — can be complicated. You may read a book young, fall madly in love with it, imagine and reimagine its moments, but then grow up to temper your feelings. With adulthood comes a strange sense of artistic subservience. You’re wired to disown those adolescent first-love notions of the book; you try to understand it in the context of how others read it, what the general legacy of the story is, or the various themes it spawns. In a way, it’s no longer your relationship alone. Suddenly, those words belong to everyone. Meaning is shared. It’s almost impossible to retain that tunnel-vision age of innocence; it’s the great expectations that take it all away. When filmmakers choose to adapt these books, fidelity becomes an extension of this syndrome. Replicating the author’s voice is seen as imperative to the exercise. A good ‘cover’ is perceived as a successful film; anything less is treated as an act of treason.

This is where one can’t help but admire the existence of Emerald Fennell. With Wuthering Heights, she’s not concerned with being faithful to the Emily Brontë novel. She’s concerned with being faithful to herself: her personality, her adolescent memories of a sprawling story, her feral version of love and obsession, her retrospective mist of digital-era lust, her female gaze as an antithesis-but-sibling of the male gaze, the irreverent wish-fulfilment fantasies of girlhood. This is very much an Emerald Fennell movie; Wuthering Heights is just the medium. Its pages are a blank canvas on which every greedy brush stroke is whatever it wants to be on that day: giggly visual innuendo, a swooning sunset, a foggy cliff, a smoky loft, masturbation on the rocks, a gothic estate, a flesh-coloured wall, a twisted BDSM subplot, a non-existent third act, lust as a function of digital-era desire. It’s a freestyle rendition of whatever Fennell imagines the revered fiction as — more in the excessive vein of Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo+Juliet and The Great Gatsby than Alfonso Cuaron’s Great Expectations.

The problem with Fennell’s vision isn’t that it’s audacious. It’s that it is consumed by this audacity; the storytelling is an empty-calorie diet that’s all sensory indulgence rather than emotional heft. Individualism becomes more of a branded aesthetic that will stop at nothing to incite unrest. Instagram eroticism is the most accessible punchline: a slug on a window that looks like sperm, the suggestive kneading of dough, a finger piercing the mouth of a dead fish in jelly, a blank-screen hanging that sounds like an orgasm. Cathy (An Emma Stone-coded Margot Robbie) and Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi) are made to look like overgrown teenagers torn between roleplay kinks and cosplay fetishes. It’s like they’re parodying period pieces that dare to be serious and melodramatic because they don't have the courage to be just that without the crutch of sexual deviance. The sensationalism of feeling is used to offset the inherent lack of depth; they’re toxic and seductive because these are traits that lend themselves to stylisation. Think The Great Gatsby and Romeo+Juliet had a radioactive offspring who learnt about the birds and the bees by rereading 50 Shades of Grey in a crusty basement library.

It doesn’t really matter how Fennell interprets the original source material. What matters is how far she goes to make it her own. Different chunks of the film seem to be directed in wildly contrasting moods. It wants to be campy and playful, but also timeless and torrid. It wants to be naughty and silly, but also intense and unpredictable. If the film were a person, it’d be that popular college girl who thrives on saying whatever’s on her mind without any filters — only to start performing this identity and being scandalous for the heck of it because it gets her the attention she needs. The film commits to every moment in isolation, but seldom bothers with continuity as a whole. Even if the protagonists are unlikable and self-destructive — which they are, in the most traditional sense — the rule here is that they cannot stop being attractive to the audience (not to each other).

I’m usually a sucker for movies that swing for the fences and defy any single definition, but there’s something so calibrated about the tonal chaos of Wuthering Heights that even its distance feels like a blood-red latex suit recycled as a red carpet. Towards the end, the two lovers switch from perverse mind games to tender tragedy, almost as if they got bored provoking jealousy and angry-lust vibes out of each other and suddenly decided to act like a YA thesis on old literature. There is no real transformation, and even the character of Nelly unfolds as an unconvincing foil to keep them apart. At some point, you suspect that the childhood un-sweethearts have taken a risky postmodern sex game too far, and they’re stuck with the over-lyrical consequences with no way back.

In short, the film is defined almost entirely by its urge to evoke responses in an age of instant gratification. It’s striking to look at in reel-sized bites, but a sweeping tale of wrecked love can’t feel like a series of Charlie XCX-scored trailers stitched together. I’m all for invention and reinvention, creating instead of recreating, but reactionary filmmaking is perhaps just as hollow as derivative storytelling. That said, I heard the collective gasp of an entire cinema hall when Heathcliff returns after years and punctures the fog with a clean-shaven face and Jacob Elordi-sized sideburns. It’s the kind of sound you normally hear when someone dies, or someone drops their towel, or a ghost appears out of nowhere. It’s a shock to the gut (or slightly below the gut), and it’s almost as if Fennell heard it while writing the scene and decided to keep framing Heathcliff as an ovary-melting brute and handsome pervert. It worked, even when he takes a submissive wife and collars her and makes her bark at the sight of visitors. It worked, even when he rode a horse for what seemed like days, only to reach too late after 5 short miles. I wouldn’t say it’s a Bridgerton-gen film, because it’s a withering representation of our relationship with thirst-trap cinema. People can get away with anything — including unwitting satire — if they’re hot enough. Classic literature can take a haughty hike.