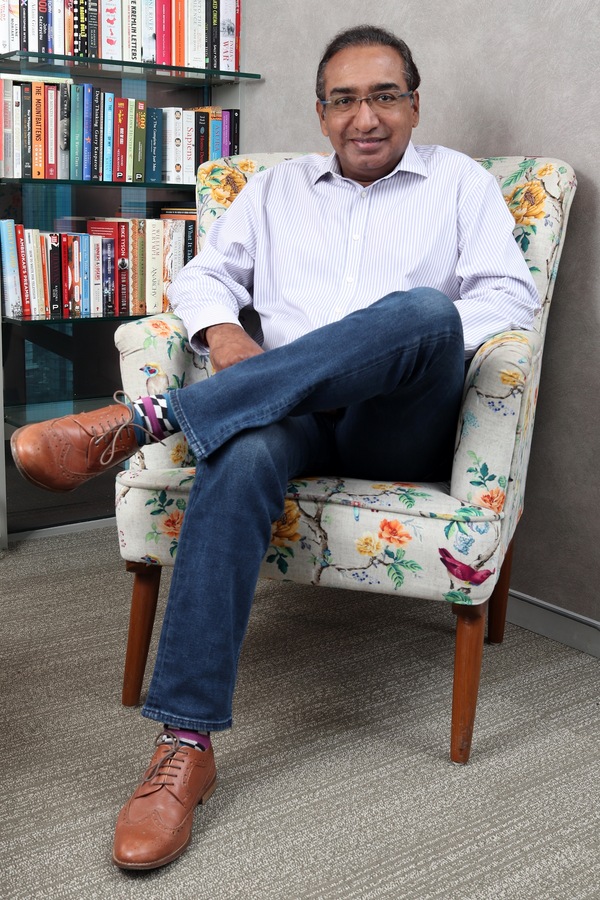

Exclusive! Applause Entertainment head honcho Sameer Nair on OTT: It's an amazing moment in technology, I don't think people appreciate enough

Sameer Nair also said that the world will be fully streamed in the coming decade.

Last Updated: 02.00 PM, Aug 17, 2022

Media and entertainment industry veteran Sameer Nair has held important leadership positions at top media companies throughout his three decades of expertise. He was a key contributor to the development of India's Star TV Network. He was in charge of developing several of India's most popular TV shows, including Sarabhai vs. Sarabhai, Koffee With Karan, Kahaani Ghar Ghar Ki, and Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi. But it was the venerable KBC (Kaun Banega Crorepati) that revolutionised celebrity hosts and prime-time reality television. It also signalled Amitabh Bachchan's transformation.

In August 2017, Sameer started a new professional chapter by founding Applause Entertainment, a studio for creating media, content, and intellectual property.

Scam 1992: The Harshad Mehta Story, Rudra: The Edge of Darkness (starring Ajay Devgn), Bloody Brothers, Criminal Justice, Bhaukaal, Hasmukh, Mithya, Avrodh, Undekhi, and Your Honour are just a few of the premium drama series that Applause has produced over the past five years. These series are currently streaming on India's top platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ Hotstar. Additionally, it has created its first batch of movies, including Aparna Sen's Busan Award-winning The Rapist, as well as an agreement with Amar Chitra Katha (ACK) to adapt all of its comic book back issues into animated series.

In an exclusive interview with OTTplay, Sameer Nair spoke at length about the completion of Applause Entertainment, his transition from TV to OTT as a content creator, adapting international content, and more.

Excerpts...

Applause Entertainment has completed five years, so congratulations. Having been a part of the entertainment industry for more than 20 years, how does it feel to be among the pioneers of a new medium of OTT altogether?

Well, I don't know who the pioneers of the medium are, but it feels good. We had been talking about this in 2011 and 2012. We worked and ALT Balaji was launched then. Meanwhile, Netflix and Amazon had gotten started, while Hotstar and others were there. So, the last ten years have been the nascent period of this, and in the last four or five years, things have really accelerated, essentially after the launch of Jio. So after Jio happened, data charges dropped, then phone connectivity and device connectivity increased. Then, almost on cue, the pandemic arrived.

So, the combination of 2016, the data charges dropping, 2019, the pandemic arriving, and here we are in 2022, with a pretty exciting and expanded market, we've had a good run. The last five years have been good for us. I think we launched in August 2017. So now we are coming up to five years. We've released 37 series so far across platforms. We've got another 10 or 15 series in production, soon to be released. We've also produced eight movies of a smaller, higher-concept kind of movie. We've been foraying into animation and documentaries. So pleased that things are progressing in the direction we anticipated.

When you started producing content for OTT, it had a niche audience. But within a year, the boom of the new medium was something else, and it was unstoppable. Did you anticipate something like this?

Well, I can't say we anticipated it. But definitely, I mean, that's the way the technology is, that is what the global streamer is. The global streamer offers you the ability to take your content to a worldwide audience. It's language and geography agnostic, and it's not like linear television that requires you to be at a certain time slot. So the internet is forever. Once it's on the internet, it's there, and it can reach anyone. They can recall it at any time. Basically, the new streaming technology is highly distinctive from what TV was. I spent my career in TV. It was always limited by geography, by linearity, which is the time-bound part of it, and then by language, as in your Hindi channel. Streaming eliminates all those three. One is that you're there forever and it's like a giant mall that you have or a library; you can do it in any language; different languages can rest next to each other; you have subtitles; and it goes across the world. If there's internet and if the service is available, you're there. Discoverability is different from having people have to discover, find, and watch you. That's tough. It requires a lot more marketing and a lot more effort to cut through, but the distribution is solved.

I suppose what we are happy about is that, obviously, whenever you look at any new technological change, and when you join the dots, when you say that, here's how the telephone is growing, here's how streaming is growing, here's how content is growing, and here's what's happening to TV. Logically, they should end up here. That's why now when I am here today, coming up to our fifth anniversary, I'm more excited about the next five years. The last five years were good, but I think the next five years are going to be great for the industry as a whole, not just us. In general, it is going to be great. Connectivity will only grow; currently, streamers in India have reached a good authentic number of 20 million paying subscriptions, not counting telco distribution and all of that. This number can reach 100 million in the next five years, and television has reached 200 million homes, which means OTT can reach 200 million homes. That's because, you know, if TVs are reached there, they're already consumer-sitting and consuming content. So they would logically consume the new content that's coming there.

India is a very rich film market. We've been watching films for the last 100 years. We are not essentially averse to content consumption. It's just about getting it to us, giving it to us in the local milieu context and with no sort of our language and feel, and making it viable. No, it's got to be cost-effective, it's got to be value for money. I think the most exciting part, rather than the last five years, is going to be the next five years. That's what really wakes me up every morning with excitement.

When you were a part of the television industry, a new set of audiences came about in 2000, the millennium, and now you witness an entire set of new audiences with OTT. As a producer, how do you keep up with the content and know what might work in today's times and what might not?

In many ways, this period, the last five or seven years, is very reminiscent of when I first joined Star TV. So I joined Star TV in 1994, which is six years before we did KBC. At that time, it was the early days of satellite television. So satellite TV was just growing. There were two million homes that were connected to satellite television, and then the scope was that this market was going to grow. If at that time you had asked anyone if you thought there would be 200 million homes connected to the TV, people would have laughed at you, saying that's impossible. But it did happen eventually. So I think it's a question of growing and growing along with the medium. What I'm grateful for is that I was on TV at that time when it was at its nascent stage and growing. Then I moved to this whole streaming business around 2012-2013, and it was nascent and growing. I got a chance to be in a nascent but growing business. At the end of the day, while technology changes, consumers, in a sense, remain the same. In a way, content consumption and content creation also remain the same. It's the format that changed. Before we did Kaun Banega Crorepati and Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi, Indian television was filled with weekly soap operas and it had small homegrown game shows. With KBC and Kyunki.., came the daily soap opera produced on a large scale and the big game show, the International Game Show, with a superstar host.

It was changed in format, but consumers were still there, still sitting in front of TVs and still watching content. Then a new format came along and changed the world. When streaming came along, consumers were still there; they were still sitting in front of their screens watching. What we're doing is instead of doing daily soaps, we're doing 10 episodes, we're doing it in seasons, we are doing more diverse kinds of content, it's not a one-size-fits-all. We can do this in multiple languages, and consumers are also open to it. A lot of credit must go to consumers for being open-minded and welcoming of new content. When you hear that a large number of North Indian audiences are liking The Great Indian Kitchen, it's a good thing. Ten or fifteen years back, that wouldn't have happened, because the technology wasn't there to get it to them. Therefore, they had no exposure to it.

When they happily watch Money Heist, Narcos, or Squid Game, it's a good thing, because the more consumers consume, the different opportunities it makes for creators like us to create different types of content. India is a very large market. So when you talk about it, even when you take a population size of a billion and suppose you say your addressable market here is 500 million, that's a lot of pockets. 500 million is the size of Europe in a sense, like it's full. Marathi is one language, Tamil is one language, and Telugu is one language. I think what we are doing now, all of us, is looking to cater to a content creation strategy that is built for this new consumption manner. People are still watching.

So at the end of the day, RRR goes on to Netflix and becomes the most watched Indian movie on Netflix globally. So it's still RRR and it's still a movie. It's still released in theatres, and we all saw it in theatres. It's not like RRR was made especially for Netflix; the consumer watching is the same. The content being created is the same, the technology is different, and then there are different tweaks to it. What the daily soap opera did to TV, I think a lot of the new series that we are making now are fueling streaming. It's storytelling of a different type.

How and when did this thirst for content creation and the backing of interesting projects start?

Well, honestly, I grew up and I've seen, I think in the 70s, every single Hindi movie that has been released. I grew up in Bombay. My mom and I are both movie freaks, so we both loved watching that; my father, not so much. He preferred the more arthouse kind of cinema, but my mother and I were real Hindi movie buffs. When I grew up, originally, I thought I'd be a scientist, and I said, "Okay, I want to get into advertising because that was a cool thing to do." in the early 80s. I tried to get into advertising, but I had to go through a few hoops before I could do that. Then I landed a job at Goldwire Communications in Chennai, which was the lead agency for MRF. But even there, I landed a TV job in the sense that we started acquiring and putting programmes on Doordarshan. So I got an early exposure to this, to essentially putting programmes on television and understanding the broadcast medium. I was doing that. I became an ad filmmaker. I was doing those kinds of things.

Then I got a break on Star TV in 1994, and then I arrived. I enjoyed Star TV, and then I've been on TV since then. I spent the better part of the next 20-odd years in TV. When I left NDTV Imagine, my first sense was that I think the next big thing is going to be streaming, so I don't want to go back to TV. I've also done a lot of TV, so I didn't want to go back to doing more TV. So I got started on this.

At the end of the day, I'm naturally a storyteller and I like to put things together. I'd like to be a producer. I'd like to know about our business, as they say, that it takes a village to make a movie. It's about managing a large number of people; no different collaborators, different creators, a variety of egos, tantrums, economics, financial dynamics, hits and flops, managing men, material, and resources; you have to manage all of those things, which I enjoy doing. I like telling stories; it becomes a happy combination for me. I was really fortunate when I met Mr. Birla five years ago, and I proposed this idea to him. He is a patron of the arts himself. He really loves art in all its forms, and he really wanted this idea of creating a content studio that would make content and then sort of licence it to the platforms. Both of us, sort of novices, were in sync about anticipating the needs that were going to arise. We were able to create a solution to fill that needed gap. So there were two risk factors here. One is identifying the need gap and saying, "Okay, there is going to be one." Also saying let's set up a studio that is going to create content to feed that need. All credit goes to him because he really sort of backed this idea and has been a really fantastic patron, to say the least.

You have been contributing to the best content on OTT. How did you decide on which project to back? Do your instincts come into play for this?

The thing about data is that data is a collection of information about something that's happened in the past. That's always data. So when you say, "No, let's look at the data," it means you're looking at something that's happened in the past. You're going to now use that data to make something for the future. So that's how the relationship works. What I think is that all of us, you, me, everyone, are products of our own data. You have spent your life in a business, and I've spent my life in a business. I've been creating content for many years, and I've had many hits and misses. It's not only been hits, but a lot of misses as well. In all of that, there is learning that occurs. So when people talk about data, I think of all human beings and every decision we take is a database decision. We are already doing that, right? People are just making a big deal about it. A lot of my decisions are based on experience. which is data, which is based on gut, which is data, which is based on insight, which is data, which is based on listening to consumer signals, which is data, and then a lot of common sense, which is also data.

Now, let's say somebody comes in and pitches an idea to me, and I don't know. I'd heard of an idea like this before, and it was terrible and flopped. I don't know whether we're ready to do it again; that's a data decision. So I think, in many ways, the creative industry likes to romanticise instinct and tries to romanticise gut. But actually, for all great creators, great filmmakers, and great storytellers, a lot of it comes out even when they talk about stories. When we discuss Leo Tolstoy or Charles Dickens, we are talking about very authentic stories that are often based on lived experiences, and lived experiences are data. I've been poor, and I've written a story about this. You can feel my pathos and angst with data. It's not that you're not imagining this stuff. A rich man cannot write a poem or a story because he does not have the necessary data sets to do it. I'm a great believer in data. I love to listen to who's doing what, what's happening, what the new trend is, all of that, and then use all of that to try and anticipate what I think is going to work. I've been fortunate. God has been trying to get it right more often than I get it wrong.

When Scam 1992 was released, it created a new benchmark in OTT. Is there that much pressure or excitement on you as a producer to deliver what you've created?

No, we don't. We don't take the pressure at all. I mean, it's nothing like that, it's not a competition. One for us with ourselves, one for us with anyone else. It shouldn't be a competition for anyone else with us because, finally, at the end of the day, we make a show, we release it out on a Friday, it's a big hit, it blows the world apart, all of that happens. But then, like all great explosions and great starbursts, if you will, it dies down, the halo dies down, and the explosion sort of subsides. And then the next thing comes along. That's how movies work. So a big movie comes in, it's a big smash hit, it turns the world on fire, and then the next one comes along. It's good because when things do well, they help raise the benchmark, they help raise consumer tastes, and they help raise consumer expectations, so that's good for the industry. However, to say that the next one must be better than the previous one is never true. Things are also unique; Scam 1992 was a one-of-a-kind event. So when you take something like Criminal Justice, you can't compare it to a Scam. It would be wrong to compare because it's got nothing to do with all these different kinds of shows. What we enjoy doing is to look at focusing on consistently high quality, consistently different storytelling, and consistently trying to raise the bar. So that's our approach. It's a big idea that will have a global impact.

We are going to show Mahatma Gandhi as a world-famous figure. We are going to use this as an opening to tell the story of the Indian independence struggle. This is going to be a sweeping series across three seasons. We bought Ramachandra Guha's books and we've cast Pratik Gandhi. But there's no pressure in that sense. It's not that. This has got to be better than that. It's got to be a story that when you see it, you should be captivated. And if you are captivated, like you, millions are captivated, it's a victory. We don't keep count of that because it's like if you compare it to sport, if you go to ask Sachin Tendulkar which of your centuries is the best century, there is no such thing as that. You want to be a consistently good player, that's all.

How did you come up with the idea of bringing Amar Chitra Katha to OTT?

I grew up reading Amar Chitra Katha. That was the only thing we had. We either had Batman or Superman comics in Bandra or Amar Chitra Katha. I have read those comics a thousand times. As I grew up, the only thing I saw was a lot of foreign animation shows, but I have never, ever seen anything like the way I imagined the Mahabharat was, the way I imagined Shiva's third eye opening and the burning of Kama Deva. Finally, when the shows started coming on TV, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, they were also very worshipful in that sense. And I always imagined the Amar Chitra Katha series, and especially our mythology series, to be very dynamic, like Greek gods and HeMan. In my head, things were moving much faster and had a lot more sound and fury in them. So I've been pursuing ACK for a long time.

I've been trying to do a deal with them since 2005. While I was at Star, we were fortunate that now we've finally gone and managed to do this. We've signed up for the catalogue, and we are looking to animate the entire catalogue. We are starting with ACK Jr.-Panchtantra Tales, Jataka Tales, and we're doing Mahabharat. We're looking to essentially take these stories, especially the epics, and make them available to an international audience at a standard that they are used to, not at a standard that we are used to. We want Marvel to be consumed like how the world consumes the Greek myths. The world should consume Indian myths. That's the plan.

Are you planning to make movies for OTT or theatrical release as well?

It's not about being OTT or theatrical. We started out by taking a few more small steps towards it. We didn't want to go big straight away. We greenlit a whole bunch of very high-concept and thought-provoking movies that really caught our attention. So like Aparna Sen's The Rapist, Tahira Kashyap Khurrana's Sharmaji Ki Beti, Saurabh Shukla is doing Jab Khuli Kitaab, Nandita Das is doing Swiggato with Kapil Sharma. There's another one in Twinkle Khanna's short story, Salaam Noni Appa. There's, of course, a beautiful movie called The Lovers with Vidya Balan, Pratik Gandhi, Sendhil Ramamurthy, and Ileana D'Cruz in it. So this is a bunch of movies that came to us, we really liked them, and we proceeded with them. Some of these will come straight to an OTT platform, some will go to theatres. That really depends on what the market dynamics are.

Now as we're going forward for the next five years, as we look forward, our plans are obviously not to create bigger properties, to try and create new slightly larger franchise movies, to create stronger brands basically. I'm a big believer in the theatrical business. So I think that the theatrical business must be protected. It should not die out. This whole thing about everything being available on OTT platforms and therefore you don't need theaters, is not good for business. It's also not good for the consumer experience because, finally, a theatrical release does create a cultural moment. You have to go on the weekend and see it. What happens with streaming or with TV is that you can always choose to see it later. When a movie is released, you may miss it this week, thinking you can watch it the following week, but you are missing the moment. But theatrical experience creates a cultural moment. I think it's good because there's revenue there, there is a revenue stream out there. People want to go to theatres now after a pandemic. A lot of people want to get out of their homes. They want to get out and go there. That's why, you know, restaurants are full and travel has picked up. Human beings are naturally social animals. We want to be out there meeting with people. This is based on the assumption that now you sit in your house, you don't ever leave your house. You order food from Swiggy and Zomato; you get Netflix and Amazon in the house. I think that's odd, online education. everything online.

Our ambition for movies is to do bigger or to do different, to do multi-languages. We're focusing a lot on creating content in Tamil, Telugu, and Malayalam as well. We've already done the Kannada show with Humble Politiciann Nograj. For the next 5–10 years, the best thing about this business is that the streaming revolution allows us to create any kind of content, in any language, and make it available to audiences everywhere. There is no sort of limitation. If a good idea comes out of Assam, technically speaking, we can make that series or movie, produce it well, and then make it available to a global audience so they can all consume it.

So the question is only about the quality of content. Malayalis, Tamilians, and Hindi speakers are making great content. Much like how the Americans did, or like how the Koreans did, there is no reason why we cannot become a global soft power using Indian content. We look at Korea. It is a tiny country, the size of Kerala or something, and we look at what they've done. They've created a global phenomenon because it's a part of good storytelling at an international standard of quality.

Do you think it might reach a saturation level as well?

Always, it does. But the good thing about stories is that, what is saturation? Saturation is, oh, there are too many stories, right? But then the thing about too many stories, too many series, too many movies is that it creates an automatic Water finds its own level, so it settles down because the saturation is more connected to the audience. As a result, they may become tiresome to the audience. Assume that audiences have grown tired of this and no longer want to watch. So TV has given them 20 years of daily soap operas and KBC season 18 or whatever, and they're still not fatiguing and still watching it. I believe that these types of series that are available on streaming are shorter, with 10 episodes, a lot more variety, and there is so much more now available. Not everyone can see everything, and you shouldn't either. Actually, when you get on to Netflix or Amazon, there is so much global content available. You don't see all of that, right? You see a few things, and you have your taste. What happens is that consumers then end up existing in their own sort of cohort. I love Nordic noir, crime thrillers, or romances; that's what I love to do. Now I watch that and a lot of that gets made. Maybe somebody else might want to watch "Adult Comedy," so you watch that. Everything can exist, and everything can happen. Some genres become more universally popular, some become more niche. I love documentaries; I watch them all the time. Maybe it's an acquired taste, but maybe not everyone else likes to see that. Fatigue is very far away. This is a very early stage for the streaming business. India's content will be fully developed within the next 5–10 years. The world will also be fully streamed. We are finally heading towards Marshall McLuhan's famous Global Village. It's now happening that in front of you, there's a screen, and you click on it, and you can watch content from anywhere, and it's all there next to each other. It's an amazing moment in technology that I don't think people appreciate enough.

You have been adapting books and, of course, international shows from other languages. How do you decide what kind of international content might work for an Indian audience?

The first thing we do, of course, is to select the content that we think will work for India or content that is more universal and that can travel, as compared to being very distinctive. Sometimes you come across shows that are very unique and very special to something happening in a region, and then that becomes harder to translate. You obviously look for more universal themes. Shows like Rudra have a universal theme. Call My Agent is universal, so is Hostages. The Office is universal.

I don't agree that The Office didn't work. I think we put on a fantastic show. I'm so sad because what happens is that the thing with this is that it also requires us as content creators, and I've been a programming head on TV. I know how it works. Sometimes what happens is that it's not just enough to say that, okay, we made a show, we put it out there, we didn't get a good enough response from the audience, so we're not doing it again. TV was not built in this manner; it was built by executives who were passionate about what they were doing and creating. Their initial run of The Office was six episodes in season one, and it was very unsure as to whether this could go forward or not. They proceeded to revive it and did seasons two, three, and four. They made 187 episodes in the US. Seinfeld came on air. It was like, "What on earth is Seinfeld?" Currently, Seinfeld is the most viewed show globally, and Netflix is buying it again and again. I think a lot of this also requires a little bit of faith and belief in things. Otherwise, you make the first shot, and you realise it. Maybe the market was too small, or maybe your audience size was too small. The Office came out two or three years ago. At that time, the streaming market was much smaller. Right now, you can argue the streaming market will become four times its current size. Maybe now data will give you different inputs. I think a lot of content and creativity also require a vision. Many times, consumers don't know what they want, so you've got to give it to them. We don't know if consumers want KBC, so we are doing it. We are making KBC and it was the first adaptation I did. We purchased it in India. We made it a fully Hindi show with Indian questions and mythology and all that, with Amitabh Bachchan speaking perfect English and Hindi, and it blew the market apart. Researchers say that if you do a game show with an aged superstar as rehearsed, it will become a super success. That is more of an instinct, more of a belief, and more of a pushing it forward, saying, "Listen, this is a great show, and it can travel, it can be done in other countries." Who Wants to be a Millionaire? It has gone on to be made in almost 80 countries worldwide. I think the way we look at adaptations is like that. We say that this is a great show. I think it ticks a lot of boxes: themes of the universe, entertainment, appealing to a larger denominator, and it can be adapted into our context. So, like, criminal justice is a show. We've got middle-class people. We've got a criminal system, we've got a justice system, we've got jails. Now it's a question of writing it in that manner, Luther. It's completely adaptable as Rudra because we've got cops, we've got crime, and we've got one Dark Cop living on the edge of darkness. It's not an impossible thing, and then in the writing, what comes out is that it's all the dialogue. So, even if the broader context and the broader plot are the same, it is the dialogue. We turned Fauda into Tanaav, which is set in Kashmir for us. So, for the Israelis, it is Israel versus Palestine. For us, it is not something versus something, it is actually a story set in Kashmir, which is India, and it is about infiltration into India, specifically into Kashmir. It's about, you know, those two sides of the story, so it's an adaptation in that sense, and that's how we do it.

Ditto for books. If you read Scam, the book, it's more of a non-fiction, fact-oriented book. The way Sucheta Dalal has written, it is a very factual book; it's a piece of journalism. What we've done is we've taken that and made it into a piece of fiction to entertain. It's not a journal, so you can't say that Scam is a journalistic piece. It's not a documentary, it's a fiction series. That's how we adapt; we make those tweaks. Even our latest show, Avrodh Season Two, that's come out, is based on a story from Shiv Aroor and Rahul Singh's book, India's Most Fearless. When the series gets made, it is considerably different from the story. There are nuances, there are all sorts of editions, and that's the nature of the audiovisual medium. So, the written word and the word that is formed are a little different.

Subscribe to our newsletter for top content, delivered fast.