Manto: Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s nuanced depiction of the pained author stands the test of time

Before Saadat Hasan Manto’s 67th death anniversary, a revisit to Nandita Das’ film and its inspired portrayal of the author’s life.

Last Updated: 08.28 PM, Jan 18, 2022

As Nandita Das ventured into her sophomore directorial following 2008’s award-winning Firaaq, the ones aware of the subject, waited with bated breath. A determined undertaking to highlight the life and times of noted author and poet Saadat Hasan Manto, Das’ film explored the birthing pains of two nations after the scathing event of Partition.

Simply titled Manto, this film is a beautifully developed prestige piece that keenly follows Manto through his years of creative glory and a consequent, hard fall into oblivion.

A brief look into Manto’s life will instantly prove that Das had a rich bank of cinematic complexity to fall back on. A thoroughly troubled writer, the mercurial author was tried for obscenity on six instances, thrice in British India, and the remaining in Pakistan.

A brutal upholder of truth, Manto was both addicted to and frustrated with his times, always hopeful that the two nations would never separate, and he could still be a part of his beloved Bombay (now Mumbai).

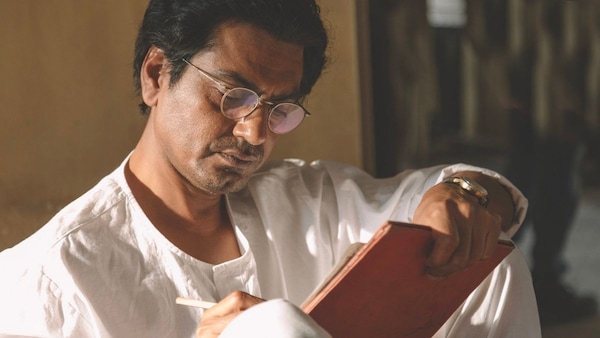

The film opens precisely on this optimistic note where Manto is seen enjoying a throbbing literary scene in the bustling city. A brilliant Nawazuddin Siddiqui embodies the writer as he produces personal work over and above his tryst with Bollywood scriptwriting.

Manto argues with tone-deaf producers and indulges in impassioned debates about censorship with fellow poet and writer Ismat Chughtai. His personal life is with wife Safia (played by the inimitable Rasika Dugal) and their beloved daughter.

Yet, Das is mindful of underscoring every moment with Manto’s continual restlessness – as a citizen, a dissatisfied author trying to prove his relevance and a steadfast rebel. In one of the court trials, Faiz Ahmed Faiz says that he would never consider Manto’s works as ‘obscene’ but immediately follows it up by saying he’d not consider them elevated literature either.

The camera is quick to pan on Siddiqui’s face, as a hush of pain crosses his countenance. He winces for a second and the camera pans back to the courtroom. Multiple scenes later Das brings a callback to this instance when the viewers understand that Manto was still nursing this hurt.

Such intimate moments of vulnerability succeed in building a genuinely lived-in character. A rounded depiction of an eccentric artiste is a rather difficult task to achieve, but Das seems to have aced this one.

Manto’s incessant anger; his anguish despite his pride and ego; his inability to accept his work as inferior and at constant war to prove thus; his guilt at not being more present for his family; his contempt of bigots and his adoration of children – all take up significant places in Das' narrative.

A fond collector of pens, Manto wrote with a pencil.

Siddiqui, who had till then been part of films like Raman Raghav 2.0 and Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox, and the much-celebrated Netflix series Sacred Games, took up a completely different avatar with this feature.

Stepping away from playing wacky antagonists, Siddiqui donned Manto’s garb, astonishingly transforming his physicality as well. Siddiqui’s Manto was ruminative, considerate, hurt, and cynical.

The one main aspect about Manto’s life that Das ably captures is the author’s most prized possession that he never got to indulge in – his undying love for the city of Bombay. A beautiful muse that is ever-elusive to the yearning lover, Bombay decks up in all its glory under Das’ lens, whether it be the hustling main centres or the dingy, congested alleyways of Manto’s world.

During a particularly touching moment in the film, Manto says about Bombay, “Yeh sheher sawaal nahi karta,” (the city never asks you questions), harking back to his personal battles to uphold his works. He even declares that the only way he would ever move to Pakistan would be if Bombay were to shift there.

In fact, audiences even see a Manto, soaked in despair as he hallucinates about asking Chughtai to fulfil his wish to return to Bombay at least once. Calling himself a "chalta phirta Bombay" (a walking talking Bombay), he simply confesses “Mera sab kuchh wahin to hai (all that I have is there)”.

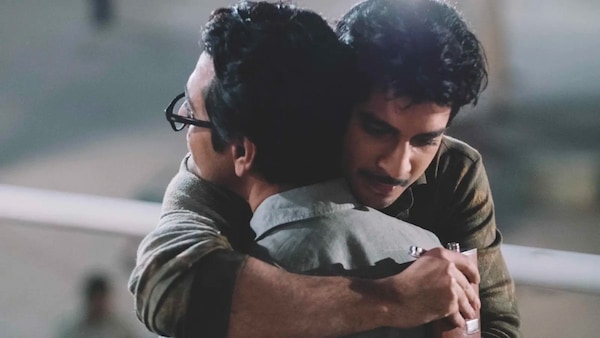

Hence, the sudden decision to move from the city is not only impactful, but evocative of the author’s excruciating pain in having to make this decision. In a scene with his longtime friend and associate, actor Shyam (played by the menacingly charming Tahir Raj Bhasin), Manto realises the hatred brewing in his friend's heart for Muslims post the bloody riots.

Shyam’s reticence and curtness unnerve Manto and he plainly says Shyam one day might want to kill him too. Shyam retorts with a “you’re not Muslim enough.” And Manto replies saying, “Itna to hoon ki maara jaa sakoon (I am Muslim enough to get murdered),”

Das achieves with Manto, a skilful depiction of the author and the gleaming ray of hope he lived with, till his last. She stitches a realistic, endearing account of the author and his works that were not only prevalent for its times, but a forewarning for the future years when nations would still crumble under the subjects of religion and freedom. Manto, thus, is a cinematic mouthpiece for resistance and standing up against unjustified entitlement.

Watch the film here .