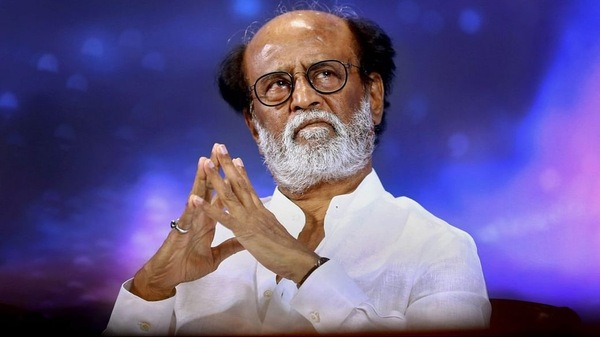

Rajnikanth Returns: Will his new movie be India’s Black Panther moment?

- Sudhish Kamath

LiveMint

Last Updated: 01.30 PM, Feb 14, 2022

Some 93 minutes, 30 seconds into K. Balachander’s love quadrangle Aboorva Raagangal (1975), an unkempt-looking man in a loose tie, untucked shirt and worn-out jacket dramatically pushes open the gate and makes his first onscreen appearance.

The film, divided into chapters, kicked off a new one with that shot. The entry was announced by a title card, “Sruthi Bedham” (scale change). Indeed, the scale had changed.

For with that low-angle long shot, a former bus conductor made the most important entry in the history of Tamil cinema. Someone who would go on to sell billions of tickets.

A dark-skinned outcast of an anti-hero had sneaked into a world of showbiz that had been reserved for the fair-skinned because the good old movie camera preferred it that way.

Though he started off playing variations of grey and all-out dark roles—an alcoholic in Aboorva Raagangal, a village bully who attempts rape in 16 Vayathanile, a rapist in Moondru Mudichu—Rajinikanth cemented his position as a serious actor with complex character roles in movies such as Bhuvana Oru Kelvikkuri, Avargal, Aarilirindhu Aruvathu Varai and Netrikkan before he starred in remakes of Amitabh Bachchan films. Billa, for instance, was a remake of Don, Velaikkaaran of Namak Halaal, Thee of Deewaar, and Panakkaran of Laawaris, to name a few. All these films channelled the rage of the angry young man in the southern context.

Towards the end of the 1980s and all through the 1990s, Rajinikanth evolved into the quintessential south Indian chauvinist hero who wore the uniform of the working classes (taxi driver in Padikkathavan, auto-driver in Baasha, milkman in Annamalai, factory worker in Uzhaippali) and rose to become the undisputed “superstar”, influential enough to change governments. His famous, “Even God cannot save Tamil Nadu”, is said to have cost the late J. Jayalalithaa the election in 1996. NextMAds

Political attacks on his smoking and drinking onscreen meant he had to take responsibility for setting right the wrongs of his cinematic career—he gave up the very cigarette that defined his style and persona on screen. Over the last decade and a half, we have seen the evolution of a family-friendly superstar. Like a James Bond you wouldn’t mind introducing your sister to. The cigarette was replaced by a biscuit. But the style remained—the way he would flip his sunglasses, the swagger, the way he would run his hands through his hair.

Any rare attempt to move away from what people expected bombed. Case in point, Baba (2002), a masala-meets-spirituality film he had written himself.

After the twin box-office failures of the animated mythological Kochadaiiyaan and the generic revenge drama Lingaa (both in 2014), Pa. Ranjith, a Generation Next writer-director of the highly acclaimed sociopolitical drama Madras (2014), was given charge of reinventing the Rajinikanth brand. thirdMAds

Until Kabali (2016), Rajinikanth, now 67, had fought shy of playing his age. He had played older characters earlier in his career, including saint Sree Raaghavendar in his 100th film of the same name in 1985, but the trappings of superstardom—and market forces—compelled him into an image trap over the later, post-1985, part of his career.

With Kabali, Rajinikanth employed style as a weapon of empowerment.

In the film, the director’s voice rings loud and clear: He makes his hero read Y.B. Satyanarayana’s My Father Baliah (a book on what it means to be a Dalit in India) and drops enough clues through the film about Kabali’s Dalit identity. For this champion of the masses defies the bad guys by wearing their uniform—the “coat-suit”. fourthMAds

The dark-skinned hero had come a long way from the time he wore the uniforms of auto-drivers, milk vendors, factory workers and taxi drivers.

The film’s punchline, translated, goes somewhat like this: “If you think my prosperity is a problem, I will prosper, da. I will wear coat-suit, da. Will put one leg over the other, and sit in style, in front of you. If you can’t deal with it, die.”

Despite mixed reviews, Ranjith ensured a somewhat smooth transition, enabling the superstar to embrace his “greys” in the movies—almost two decades after Bachchan had made that transition on screen.

Critics and the masses loved the fact that Rajinikanth was now ageing gracefully. Kabali was the superstar’s first hit in six years, since director Shankar’s 2010 sci-fi action bilingual Enthiran (Robot).

This may explain why Ranjith got a second shot at directing the actor in the forthcoming Kaala. It’s another sociopolitical drama, this one is set in the slums of Dharavi in Mumbai.

Rajinikanth signed Kaala well before he announced his entry into politics, but fans are keen to see if the film reflects his cinema of the early 1990s, with punchlines alluding to a possible entry into politics. They may not translate well and you might have to read them with a straight face: “Nobody knows how I’ll come, when I’ll come but when I have to come, I’ll come” (Muthu, 1995); or “My way, unique way” (Padaiyappa, 1999); or “Or God ordains, Arunachalam completes” (Arunachalam, 1999).sixthMAds

Ranjith, a Chennai-based Dalit film-maker, has sympathy for the marginalized but sociopolitical films don’t always translate into box-office success. Understandably, then, the film-maker is under pressure to measure every word he puts out there. When contacted for this story, he preferred to have the questions sent to him so that he could take his time with the answers.

Rajnikanth started his career with Tamil cinema’s Billy Wilder, K. Balachander, but went on to work with film-maker S.P. Muthuraman for almost half his career before he began working with Suresh Krissna, P. Vasu, K.S. Ravikumar, and, ultimately, Shankar, who delivered a superhit with Sivaji (2007). Shankar signed the actor for Enthiran (Robot). Critics observed that if Sivaji was Shankar doing a Rajinikanth film, Enthiran (Robot) was Rajinikanth doing a Shankar film.

I ask Ranjith if he had managed to get the superstar to do a Pa. Ranjith film. The response is diplomatic: “It is amazing how these thoughts or discussions never came up in the conversations between Rajini Sir and me,” he wrote on WhatsApp.

“He saw my work in Madras and called me. From my debut feature, all the films I have made so far are story-specific. So, when Rajini Sir and I met, we knew exactly what to expect of each other. That’s how we delivered Kabali. After Kabali, Kaala became possible also for the same reasons. He liked my work and believed that I can deliver something interesting yet again.

“When we first met to speak about Kaala, Sir was keen on making a commercial film.

“When I went back to him with the story of Kaala, the commercial element and the sociopolitical aspect in the story excited him,” writes Ranjith.

On 31 December (Kaala was still in the making), Rajinikanth announced that he would enter politics and contest all 234 seats in the 2021 elections, finally setting to rest all the speculation.

Was the script changed or tweaked keeping in mind Rajinikanth’s political ambitions? “When we were shooting Kaala, his political entry was not final,” clarifies Ranjith. “Nothing in my stories changed and Rajini Sir is also a person who does not expect these things. He does not in any way interfere in the story or ask for things to be changed.”

While Ranjith’s anti-caste cinema bats for the downtrodden, Rajinikanth’s politics has a hint of spirituality. His faith in God (and religion) is well-documented and part of his political rhetoric. I’m curious about how the twain meet.

Ranjith explains: “Rajini Sir is a superhuman to the audience. My stories have protagonists who are superhuman in day-to-day life because of the conviction, goodwill and sense of justice they exhibit. When these two elements combine on screen, it makes for magic. We have tried creating that in Kaala. People will relate to the character Kaala and his journey of conviction, and that is the only influence this film wants to have on its audience.”

As the teaser indicates, Rajinikanth plays Karikaalan from Tirunelveli, the protector who fights for the poor (Tamils in Dharavi in this case, as opposed to Tamils in Malaysia in Kabali). He celebrates all things black—he is dressed in black, with matching dark shades. When a white shirt-sporting Nana Patekar, presumably a politician, says,“I want to make this country clean…and pure,” the superstar shoots back: “Black…is the colour of hard work. Come to my chawl and you will see dirt turn into colour.” If most mainstream cinema has been about good versus evil, depicted in white versus black, respectively, Kaala’s teaser tries to make a case for black as the colour of the hard-working poor and white as schemingly evil.

This isn’t the first film where Rajinikanth is playing the protector of the poor in Mumbai. One of the most iconic Rajinikanth films, Baasha (1995), a loose reworking of Mukul Anand’s Hum (1991), featured Rajinikanth playing a godfather-figure, posing with a Great Dane for the posters.

Twenty-three years later, Rajinikanth is back in Mumbai. This time, not in rich man’s clothes (as he did in Kabali or Baasha), or posing with a foreign- pedigree canine. He’s in a black kurta and black lungi, with a stray for company.

Ranjith insists the subversion wasn’t intentional. The stray in Kaala’s poster is a character in the film. “I wanted the character Kaala to have a stray as a companion in the film. I did not intend it as a comparison or as a tribute in any way,” the director clarifies.

It’s only fitting, though, that the cinema of Ranjith celebrates the stray rather than conforming to conventional notions of pedigree or race.

It’s easy to see why Rajinikanth the superstar would say yes to Kaala. He has owned the black identity, and has associated the colour with style. There’s a whole sequence in Shankar’s Sivaji that celebrates black skin, including the song Oru Koodai Sunlight, where the visual effects team creates a white Rajinikanth to prove why it just wouldn’t be the same.

It’s a colour he was chosen to play in his debut film, as an abusive alcoholic. Today, it’s the colour of a champion. A hero.

On 7 June, we will find out if Kaala does for Dalits what Marvel’s Black Panther—the third-highest grossing blockbuster and the highest-grossing superhero movie of all time in the US—did for black people. Become a milestone film celebrating the Dalit identity.

The writer has been a film critic for 21 years and is working on a biography of Rajinikanth, forthcoming from HarperCollins.