The Sinner-Alcaraz Rivalry: When Revolution Meets Evolution

Rahul Desai chronicles two prodigies, one court, and a contest that rewrites the rules of tennis greatness.

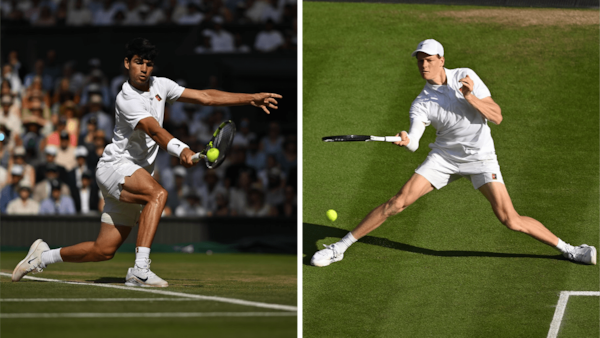

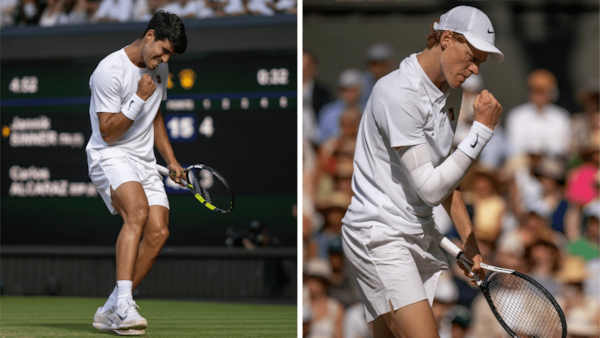

Carlos Alcaraz fights back against Jannik Sinner at the Wimbledon 2025 Men's Final.

Last Updated: 05.20 PM, Jul 16, 2025

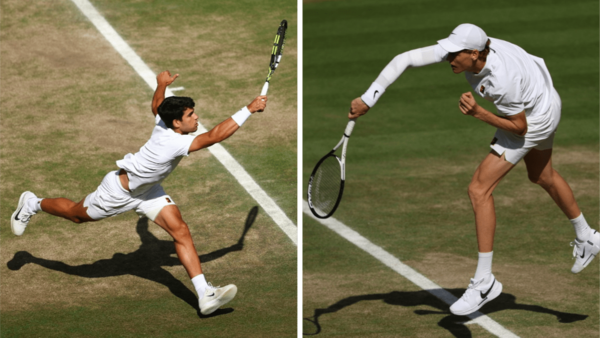

IT IS WIDELY BELIEVED that the only player capable of defeating Carlos Alcaraz is Carlos Alcaraz. This would imply he's a mercurial genius — Federer and Nadal by day, Marat Safin by night. This would also imply that triumph and tragedy co-exist on his racket as a symphony of conflict. He decides his own fate: those mid-game brain fades, those agent-of-chaos grins, those heart-in-mouth-timed drop shots, the Rishabh Pant-coded recklessness against the run of play (and logic). It's like watching two timelines — a child discovering tennis and an adult grappling with its consequences — jostling for ownership of one 22-year-old body. The shot he ends up making unfolds like a decision in a candy store. Winning the point feels incidental; playing it is the whole point.

Maybe we've romanticised the innocence of his style, but it's not untrue. The reason it always seems as if Alcaraz controls the flow is because, at his best, the sport looks like a game again. Out of nowhere, he shows us glimpses of what is possible: transcendental strokes of joy and (e)motion that puncture the anti-spontaneity of pro-tennis. The micro-suspense is not for the lily-livered: nobody knows what's coming, because neither does he. Out of nowhere, he also shows us shades of what is probable: strange dips in intensity and engagement with the ball, not the opponent or the scoreline. When he's down two sets to one, it never quite appears like he's down; he's just greasing his own gears and exploring the elasticity of his flair. The comebacks are nice, but the magic is in the inevitability rather than the resilience.

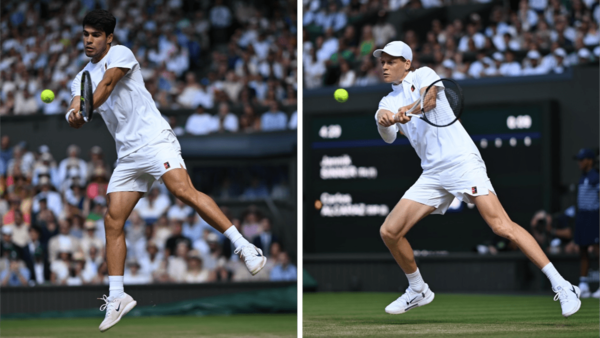

On Sunday evening, however, Carlos Alcaraz lost more than just the 2025 Wimbledon final. He lost the freedom to flirt with invincibility on his own terms. He lost the agency to be defeated by Carlos Alcaraz. He lost the choice to lose. Because on Sunday evening, it was Jannik Sinner who won, not Alcaraz who lost. In the third and fourth set, you could tell that Alcaraz's joy was forced to grow up. He gestured to his box. He berated the air. He asked the gods. He wondered and wallowed. Sinner exhibited such mechanical speed, precision and power that he robbed Alcaraz of the power to toy with his own destiny. He snatched away his superpower to be human. Alcaraz's patented inconsistency was flattened by the inability to do better.

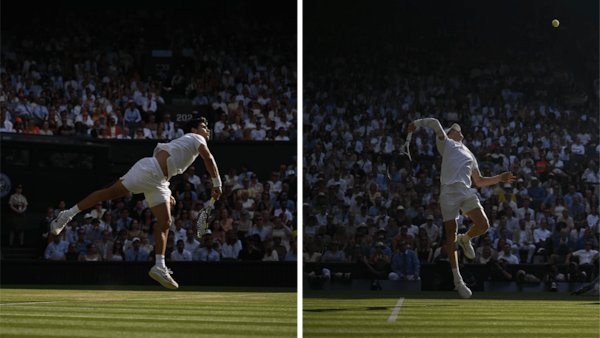

Alcaraz could only react, not act — he became predictable from the baseline, cautious at the net, hesitant in his calibrations of rhythm and direction. The child was gone, only the adult remained. There were times when Sinner forced his errors, but more painful for Alcaraz were the times when Sinner outplayed him at his own game. Like the scarcely believable final rally of the second set, when Sinner countered spontaneity with spontaneity; a cross-court forehand slap made time stand still on a clock that was designed to tick for Alcaraz. Suddenly, it felt like the Spaniard's language had been co-opted. His whimsy had been punished.

It didn't come out of the blue. When Carlos Alcaraz (and the rest of the world) celebrated the five-and-a-half-hour Roland Garros miracle in early June, it felt similar to Federer celebrating his 2007 Wimbledon final win over a gritty Nadal. The moment expanded, but the threat was imminent. Alcaraz was hailed, of course, not least because it was one of the finest men's Grand Slam finals ever played. But there was also the inescapable sense of the bigger picture. Sinner had not only caught up, he had almost gatecrashed Alcaraz's clay-court dominance. He went toe to toe on the red dirt of Paris, arriving within a single point of dethroning the defending champion and deflating his free-flowing aura. The Italian was no longer a hard-court machine; he was on the brink of nullifying the change of surface. It didn't matter where he played anymore; the timing and agility and angles were beginning to create their own rules. His early loss at Halle on grass gave him the bandwidth to process the trophy that got away. There was the prophetic stroke of “luck” against Grigor Dimitrov in the fourth round of Wimbledon — where the 34-year-old's misfortune gave Sinner the chance to erase the narrative of fortune. The symptoms of the future were difficult to ignore.

We all sensed it, perhaps that's why Alcaraz's jailbreak on clay felt even more poignant. It wasn't a revolution of spirit or skill, it was a last-gasp resistance against evolution itself. Usually, it's older champions like Djokovic who become underdogs by virtue of the younger generations they vanquish — and the upgraded sport they keep adapting to. The greats lord over an era, but the legends find a way to evolve and lord over multiple eras; the 1990s generation of no-hopers and strivers — Zverev, Tsitsipas, Rublev, Medvedev (to an extent) — are a testament to Djokovic's history-spanning rule. Nadal and Djokovic themselves emerged to thwart Federer's pre-eminence after he had claimed the generation of Roddick, Hewitt, Nalbandian, Davydenko and others. He managed to quell around one-and-a-half eras before the two baseliners revised the physicality and default modes of tennis.

But despite being more or less the same age, Carlos Alcaraz was the one having to defy time against Jannik Sinner. Within the same match, he was compelled to go from favourite to underdog to antique to mental monster. He did pull a rabbit out of the hat in Paris, but at Wimbledon, the same tricks were relegated to the dusty loft of a bygone age. Magic became his last resort; he went for broke with the muted flair of someone who kept breaking. Alcaraz's spectacle was subdued by Sinner's sight. Just like that, the chaos of Carlos Alcaraz was reduced to the order of inferiority — he was the weaker player, even when he wasn't.

It's easy to suggest that, in retrospect, Sinner was one point away from holding all four Slams together. It doesn't work like that, though. If he had won at Roland Garros, there's no guarantee that he'd have the hunger and drive to 'avenge' the loss and take Wimbledon. I'm not sure elite athletes — especially those at the dizzying levels of Sinner and Alcaraz — think in the rhetoric of numbers and records. Those are often stories we tell ourselves to make sense of their majesty. Naturally, Alcaraz is too shapeless a player — and too big a tennis nut — to feel like a runner-up for too long. He's now entering uncharted territory in a career that has contained generations within years: a space where he can no longer afford to be consumed by the whims of wizardry. His results may no longer be in his own hands, but his identity is. He may not be the one serving anymore, but he can still decide the nature of his returns: keep the ball in play or go for an audacious down-the-line winner?

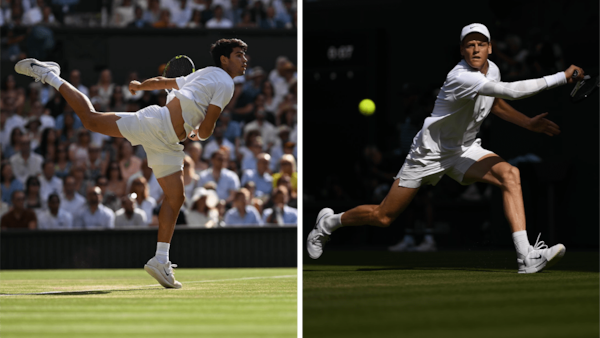

I suspect we know the answer to that. The degree of method is determined by his commitment to mayhem. Darwinism is as much his opponent as Sinner is. Perhaps the best part of this rivalry is that Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz not only complete each other, they extend the linearity of tennis. It is moving forward, and ahead, even for nostalgic Federer fans like myself. When I watch them hit the chalk and drag each other from one corner to another, it's the normalisation of brilliance — not just stray sparks of it — that gets me. It's the contest between tempered volatility and violent durability that's so alluring.

As someone wired to read sport through the lens of following, it feels a bit strange to do so in this case. Initially, I thought that being “neutral” would help me appreciate the nuances of tennis without the burden of bias. The mind is clearer when the heart is lighter. Supporting neither was the only way to maybe spot the game within the sport. But it's hard not to root for Sinner the second he leans into the ball, as if he's bending not just his knees but also the laws of perception. It's equally hard to not root for Alcaraz the second he alters the trajectory of a rally, as if he's disrupting the defense-to-offense continuum. Supporting both, and therefore neither, is the most natural impulse. To do otherwise would be to imagine only half of tennis. To do so — and most of us are already in the throes of impassioned centrism without realising it — would be to reimagine the tennis experience. It doubles the intensity of investment.

Every rally features a shifting of alliance the moment the ball passes over the net; our loyalties are volleyed, dinked, smashed down the line, served into the body and lobbed over the head. Jannik Sinner is stronger, Carlos Alcaraz is craftier, but it's the art of following that is primed to evolve. Somehow, the binaries of fandom are fading. When Alcaraz smiles and Sinner grimaces at once, we are suspended between the transience of feeling and subsumed by the permanence of participating. Resistance is futile — the modern tennis lover is a higher being.