What Sitaare Zameen Par Gets Right About On-Screen Representation

The Aamir Khan film nudges Hindi cinema towards a more inclusive portrayal of caste, religion and disability — without tokenism, writes OTTplay's guest columnist Lagan Mangla.

Last Updated: 03.29 PM, Jul 02, 2025

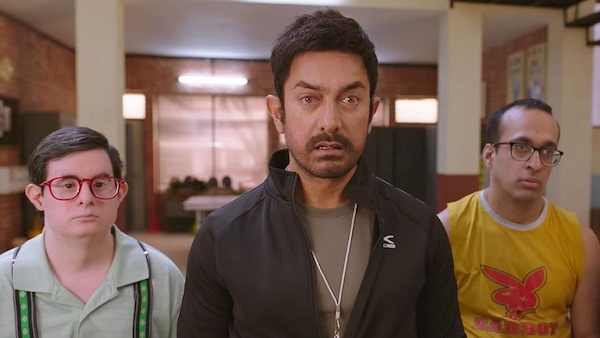

THE RECENT AAMIR KHAN-STARRER Sitaare Zameen Par has received a positive response from both audiences and critics ever since its release, which has also helped turn around the dry spell the actor has been experiencing at the box office. However, the release of the film, directed by RS Prasanna, was not entirely smooth sailing, as the CBFC refused to certify the film without some specific changes, including the addition of a disclaimer quotation by PM Narendra Modi at the start of the film, to secure a UA certification.

Sitaare Zameen Par is an official remake of the 2018 Spanish-language film Champions, which tells the story of a suspended basketball coach sentenced to community service by helping a team of players with intellectual disabilities as they prepare for a tournament. The well-intentioned film uses humour at will to strive for a kinder, accepting and more inclusive world for persons with disabilities, challenging various stigmas. The cast which makes up the basketball team are actually individuals with intellectual disabilities, which was not the case for its spiritual predecessor Taare Zameen Par (2007). Beyond this choice, the film also makes creative choices which allow for a visible presence of characters from non-dominant castes as well as representing minority religions.

An overwhelming criticism of the Hindi film industry has come from a section which has argued that Hindi films showcase a homogenised worldview, representing stories of only the upper-caste Hindu imagination. It has been argued that other subcultures of India have been co-opted by this broad cultural production reflected in wedding practices, celebration of festivals and even food practices as seen on the silver screen. A research study ‘Lights, Camera and Time for Action: Recasting a Gender Equality Compliant Hindi Cinema’ (2023) by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences found that of the 25 highest-grossing Hindi films from 2019, 79 percent of the characters were shown to be following the Hindu religion, whereas about 92 percent of the characters in these films were depicted as belonging to dominant castes.

In an interesting turn, Sitaare Zameen Par comes off as a film which pushes the envelope in terms of representation of characters from non-dominant castes as well as religious minorities. While the protagonist, Gulshan Arora, played by Aamir Khan, follows the norms of Hindi cinema as an upper-caste Hindu, many characters around him in critical roles reflect a different picture. The Delhi-NCR setting of the film allows for a cross-section of individuals from North India to be part of the basketball team being trained by Arora. For the most part, the team members are referred to by their first names, with the visible exception of the two Muslim team members – Karim Qureshi (Samvit Desai) and Golu Khan (Simran Mangeshkar), and another who is just called Sharmaji (Rishi Shahani). At least two other Sikh characters form a part of the team, while the character with the name Lotus (Aayush Bhansali) makes it difficult to understand his religious or caste background. Kartar Singh (Gurpal Singh), who looks after the team members, plays a crucial role in bridging Gulshan’s understanding of intellectual disability.

Prasanna opts for a largely Punjabi milieu for the film, a commonly used setting especially for comedy films. However, Prasanna challenges the stereotypes by sprinkling characters from non-dominant castes through the film. So, the head coach of the Delhi Men’s Basketball team is Paswanji (Deepraj Rana), who gets in conflict with Gulshan and manages to get him suspended. Judge Anupama Mandal (Tarana Raja), as her name reads in the courtroom, orders Gulshan to serve his term in community service.

This goes against the traditional wisdom of Hindi cinema, where a character from the non-dominant caste would only be shown if it is a story about them succeeding against all odds and barriers created by their caste identity. Sitaare Zameen Par does not indulge in any of that. In fact, the film gives them the authority to make their decision without falling into the trap of making it about them fighting against various forms of discrimination. In this way, the caste identity is merely incidental to the characters who are otherwise depicted as respectable professionals who significantly influence the life of the protagonist.

Now, a film must not be given the responsibility to solve all the evils in society and lead to the creation of a picture-perfect world. However, being an influential medium, cinema leads to a cultural production which can lead to meaningful conversations about important matters which require greater attention. It is in this light that Sitaare Zameen Par comes off as a significant step forward in the ever-evolving landscape of Hindi cinema, where questions of inclusion, representation, and narrative responsibility are increasingly coming to the fore. While the film follows many conventions of mainstream storytelling, including anchoring itself around a familiar, upper-caste protagonist, it simultaneously manages to subvert expectations by weaving in characters from non-dominant castes, religious minorities, and persons with intellectual disabilities without reducing them to mere symbols of struggle or pity. By allowing these characters to occupy positions of authority, agency, and nuance, the film challenges the industry's long-standing tendency to either invisibilise or stereotype marginalised identities.

WATCH NOW | Loved Aamir Khan's Sitaare Zameen Par character, Gulshan Arora? Stream more films with unusual teachers whose lessons made a mark: Iqbal (Z5); Jhund (Z5); Ghoomer (Z5); Saala Khadoos (Sony LIV)

Yet, it must also be noted that Sitaare Zameen Par’s progressive gestures operate within the framework of a commercial film that still centres the transformative journey of a lead from a privileged background. As such, while it may not be a radical departure from Hindi cinema’s status quo, it signals a slow but meaningful shift towards a more pluralistic and empathetic cinematic imagination. This worldview recognises the everyday presence and dignity of those historically kept at the margins of the silver screen. In doing so, the film does not just aim to entertain, but also to reflect a more inclusive vision of India, albeit imperfectly.