The Mother Is No Longer The Nation

Vikram Phukan explores how Indian cinema moved from mythic mothers of sons to flawed mothers of daughters, shifting its gaze from nationhood to nuance.

Last Updated: 04.42 PM, May 11, 2025

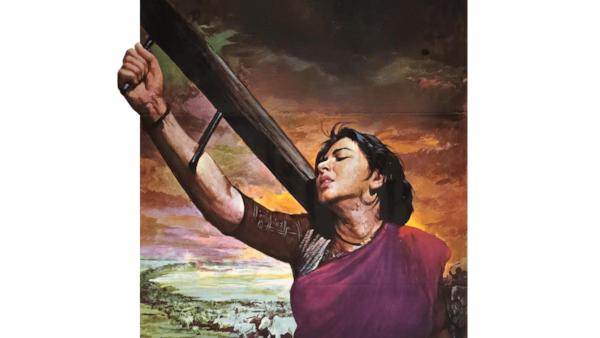

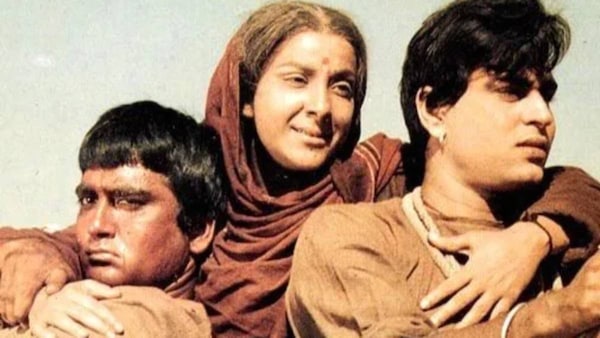

IN MAINSTREAM CINEMA, the image of the mother has long served as a loaded symbol, and most potently, a stand-in for the nation itself. In portrayals that almost exclusively revolve around mother-son relationships — from Nargis in Mother India to Rohini Hattangadi in Agneepath — the mother isn’t merely a nurturer or caregiver, but the moral axis around which male protagonists orbit.

This was never more exemplified than by Nirupa Roy in Deewar as a monument to maternal suffering, caught between sons-as-ideologies. Rakhee’s roles in Falak and Ram Lakhan follow in the same vein: she is not afforded interiority, only symbolism. The mother’s suffering grants her sons legitimacy; her endurance lends their quests meaning. In songs like “Teri Bachpan Ko Jawani” (Mujhe Jeene Do) and “Tu Mere Saath Rahega Munne” (Trishul), both featuring Waheeda Rehman, motherhood is framed as a site of sacrifice and survival. These Lata Mangeshkar melodies are steeped not just in love for sons, but in the burden of safeguarding their future against impossible odds.

By contrast, the emotional stakes in mother-daughter relationships in cinema seem to unfold within the contexts of family, identity, and generational shifts, steering clear of grand allegories. These are quiet, more interior stories in which the mother is no longer the nation and the daughter is never its inheritor. Instead, the mother is often fallible, emotionally opaque, or slipping into irrelevance, while the daughter becomes the one to bear witness, to question, to cope. These films linger in discomfort and emotional disrepair.

Take Puratawn (2025), a recent and quietly devastating film directed by Suman Ghosh. Sharmila Tagore returns to the screen as an Alzheimer’s-afflicted woman whose past is riddled with suppressed memory and buried complicities. Her daughter, played by Rituparna Sengupta, must now care for a mother who is no longer fully present, in a reversal of roles. The daughter’s task is not merely caregiving — it is interpretation. She is both custodian and mourner, trying to salvage not just memories but meaning.

While Tagore’s performance, marked by gravitas and bolstered by her star allure, suggests a larger-than-life presence, her character remains a slowly fading enigma, stripped of the grand moral authority typical of mythic mothers (unlike what she might have essayed in Aradhana, more than 50 years ago). While the script takes Sengupta through several meanderings that often feel unfocused, she is at her sharpest in her interactions with her mother.

This portrayal feels like a natural extension of Sengupta’s earlier role in Paromitar Ek Din (2000), where she finds kinship not with her biological mother but with her mother-in-law, played by Aparna Sen. In that film, directed by Sen herself, the emotional lives of women are afforded some precedence over family structure. The men are distant, emotionally unavailable, and products of the same toxic patriarchy that has stunted both women in various ways. The bond they form becomes an act of quiet rebellion — two women recognising their mutual oppression and, for a time, offering each other dignity. This depiction is all the more striking given Indian cinema’s long-standing tendency to position the mother-in-law as a virago, and a keeper of patriarchal law. In Paromitar Ek Din, the mother-in-law marks a shift from enforcer to empath, from antagonist to companion.

Sen had earlier acted in Unishe April (1994), directed by Rituparno Ghosh — a film often considered a Bengali interpretation of Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata. Sen plays a classical dancer who ostensibly left her daughter, Aditi (Debashree Roy in a National Award-winning turn), behind to pursue her art. The confrontation between them is not staged as melodrama but as emotional excavation — grievances excavated with restraint and fatigue. Here again, it is the daughter who demands answers, who seeks coherence from a mother who is composed more of absence than presence (and not due to Alzheimer’s). The title refers to the anniversary of Aditi’s father’s death, which her mother seems to have forgotten.

This mother-as-absence takes a louder, messier shape in Tehzeeb (2003), Khalid Mohammed’s Hindi-language reimagining of the same Bergman classic. Here, Shabana Azmi plays the glamorous, emotionally distant singer-mother, and Urmila Matondkar is the daughter who has spent her life sifting through the rubble of abandonment, even resenting her mother for her father’s suicide. Theirs is a relationship defined not by tragedy but by long-term erosion. When the confrontation comes, it offers no redemption. It is a filial messiness that is echoed in films like Shakuntala Devi (2020), where Vidya Balan (in the title role) and Sanya Malhotra portray a mother and daughter caught in their own complicated bond.

Even so, Hindi cinema has also given us several mothers who champion their daughters’ aspirations, despite being bound by the structures of patriarchy. In Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Farida Jalal’s iconic character quietly supports her daughter’s love while navigating a controlling marriage. In Nil Battey Sannata (2015), Swara Bhaskar’s domestic worker relentlessly pushes her daughter toward a better future, while in Secret Superstar (2017), the mother becomes the enabler of her daughter’s dreams in the face of domestic abuse. In Darlings (2022), Shefali Chhaya and Alia Bhatt share a dynamic built on camaraderie and mutual support, as they navigate their troubled lives together. These mothers are neither revolutionary figures nor overt rebels, but their quiet acts of resistance suggest an evolving emotional script for women in cinema. Unlike the mother-son films that elevate motherhood into allegory, these mother-daughter films resist abstraction.

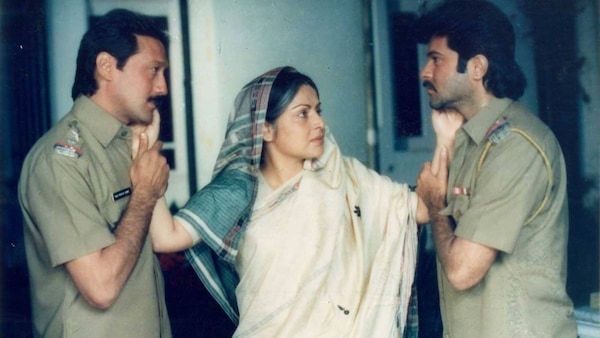

There are exceptions, of course: Fiza (2000), again directed by Mohammed, offers a partial inversion. Karisma Kapoor’s Fiza is the moral centre of the film, trying to retrieve her lost brother from political radicalism. Jaya Bachchan plays the grieving mother, but it is Fiza who confronts the world, and becomes the film’s emotional and political protagonist. The mother-daughter bond here is one of mutual devastation rather than metaphor. However, Kapoor’s character slips into the trope of the ‘good Muslim’ — the patriotic, secular woman reclaiming her brother — becoming a vessel for national rehabilitation.

Similarly, Sujata (1959) explores the delicate relationship between an upper-caste woman, Charumati (Sulochana Latkar), and an orphan (Nutan’s eponymous character) whom she takes in and raises. While providing Sujata with care and a place in her home, Charumati never fully embraces her as a daughter due to Sujata's ‘low birth’. It is only when Sujata, in an act of personal sacrifice, gives blood to save her ‘mother figure’ in a climactic scene that Charumati’s attitude shifts. The metaphor here is blunt, yet it underlines the limits of maternal acceptance when confronted with deeply entrenched social hierarchies.

And then there’s Taqdeer (1943), an odd and compelling anomaly. In the throes of a mental breakdown, a mother (Jilloobai) comes to believe that a rescued boy is actually her lost daughter. The entire household sustains this illusion as the boy grows into adulthood. This is not a film about gender fluidity in any modern sense, with gender being overwritten by grief, and the ‘son’ inhabiting a role that is more fantasy than identity. While the film doesn’t explore a typical mother-child bond, it uses maternal longing to distort the rigid structures of gender and filial relationships. Interestingly, Taqdeer was directed by Mehboob Khan, who would later revisit and solidify the mythic mother-son framework in Mother India, itself a reworking of his earlier film Aurat with Sardar Akhtar. The shift from the illusion-haunted domestic space of Taqdeer to the symbolic battlefield of Mother India marks a telling evolution: from the mother as emotional engine (via an illusory mother-daughter pairing) to the mother as national monument.

Of course, a new generation of cinema is beginning to offer more layered and contemporary interpretations. Girls Will Be Girls (2024), directed by Shuchi Talati, is a coming-of-age story that centres on a teenage girl named Mira at a Himalayan boarding school and her emotionally complicated relationship with her mother, Anila (Kani Kusruti). Mira is going through her first flush of sexual and emotional self-discovery — an experience her mother never had. The mother sees in her daughter a self she never got to be, while the daughter sees in her mother a kind of bitterness she doesn’t yet understand. These women are not metaphors. They are simply people — flawed, frightened, and trying.

Interestingly, the film’s central conceit shares a faint thematic resonance with Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Phagun (1973), another film focused on a complex mother-daughter dynamic, but one that also echoes a more direct rivalry between women, as embodied by Rehman and Bachchan. In Phagun, the mother, having lost her husband due to a marital conflict, projects unfulfilled desires onto her daughter’s relationship. In Girls Will Be Girls, Kusruti’s character — lacking her own romantic experiences — develops a bond with her daughter’s boyfriend, subtly competing for his attention. This mirrors the dynamics of desire found in Saaz (1997), where Azmi and Ayesha Dharkar play a mother-daughter pair vying for the same man. These films highlight the emotional undercurrents that arise when women’s relationships with men intersect.

In the end, what unites several of these films — Puratawn, Paromitar Ek Din, Unishe April, Girls Will Be Girls — is their refusal to mythologise the mother-daughter relationship. These films resist framing mothers or daughters as unshakable moral archetypes, focusing instead on the emotional complexities and struggles that define these bonds. And in these shifts — from myth to interiority, from nation to nuance — Indian cinema begins to tell a different kind of story, one that is more human and rooted in the real work of emotional reconciliation.