How Malayalam Cinema Navigates Devotion, Desire, & Defiance

From the moral entanglements of the 80s to contemporary self-destruction and queer defiance, Malayalam cinema has resisted ornamental romance for something far more elemental.

Last Updated: 02.37 PM, Feb 14, 2026

HISTORICALLY, Malayalam cinema has rarely indulged its lovers in grand fantasy. It has always thrived at two emotional extremes: either love is uncomplicated and seasoned into the quiet comfort of old-age contentment, or love dares to risk everything. We have shown little patience for decorative romance and gone for love that has either lived-in and gently weathered or been flung into the fire of social defiance and personal upheaval. And we have seldom lingered in the in-between, what they call the safe, ornamental middle.

The Defiant, and Fate-Driven 80s

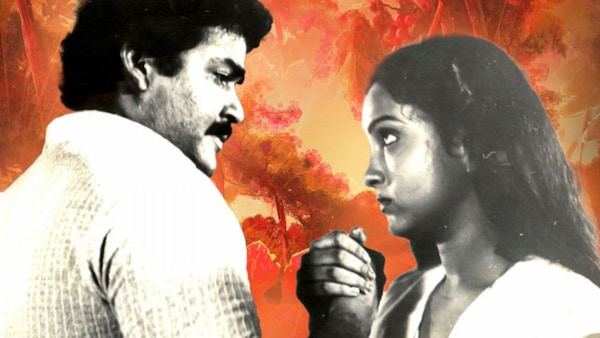

There is a reason why Padmarajan’s Thoovanathumbikal (1987) continues to be eulogised, and it is not because the romance is poignant. In fact, the film unsettles more than it soothes as it stretches itself between defiance, no-strings attachment and emotional unconventionality. When Jayakrishnan (Mohanlal) meets the charmingly aloof Clara (Sumalatha), he is still smarting from Radha’s rejection (Parvathy). What follows is more a moral entanglement than a love triangle. If Radha gestures toward stability and permanence, Clara hovers like an intoxicating guilt, desire dressed up as inevitability. And when one woman ultimately removes herself to make way for the other, the resolution feels suspiciously convenient, almost indulgent of a distinctly male fantasy. Padmarajan, ever the stylist, softens this convenience with rain-drenched frames and trippy music, lending the choice a romantic veneer. Perhaps that is why it still resonates, not because it is ideal, but because it taps into something unspoken: the quiet allure of having love bend itself around male indecision.

But his Namukku Parkaan Munthirithoppukal (1986) moved in the opposite moral direction. When Solomon (Mohanlal) realises that Sophia (Shari) has been sexually abused by her stepfather, he refuses to let the societal apathy or the corrosive obsession with “purity” dictate the terms of his love. So instead of recoiling, he seeks her out. He doesn’t internalise the stigma but offers her reassurance. At a time when purity was often lazily equated with chastity, the film made a radical gesture: it separated violation from worth. That is perhaps why this romance still endures. It is not tempestuous or indulgent but steadfast. And in its quiet insistence that love need not be policed by patriarchal shame, their romance achieves something far more lasting than spectacle; it offers dignity.

Though in the same director’s Innale (1990), love attains an altogether different register, one of renunciation. When Dr Narendran (Suresh Gopi) finally comes face-to-face with his wife (Shobana), now living with amnesia and having built a new life with another man (Jayaram), the expected cinematic crescendo never arrives. There is no confrontation or insistence on marital rights; instead, all you witness is recognition and withdrawal. When he sees that she is happy, he chooses to walk away. In that moment, he lets go of possession and ego, surrendering not because he loves less, but because he loves without entitlement. That is what makes the climax of Innale linger like an unhealed wound. It denies us closure, denies him victory, and in doing so, elevates love to something almost sublime, a quiet grace that hurts precisely because it is so selfless.

In Yathra (1985), directed by Balu Mahendra, love is measured not in intensity but in endurance. When Unnikrishnan (Mammootty) finally reunites with Thulasi after years of wrongful imprisonment, and we see her waiting, tearful, grey-haired, lamps lit in trembling hope, the moment carries the weight of time itself. This is not tempestuous romance or indulgent fantasy but love that has survived absence, stigma, and the slow erosion of years. That is why the final image lingers not as a spectacle, but as a proof that patience, too, can be a form of passion.

In Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Mathilukal, love is stripped to its barest elements. A jail inmate (Mammootty) falls in love with a woman he never sees and only hears on the other side of a prison wall separating the male and female wards. What begins as a fragile respite from loneliness gradually deepens into intimacy sustained entirely through conversation. There are no exchanged glances, no shared spaces, not even a touch. And yet, the romance feels profoundly embodied. In transcending the usual grammar of love (proximity, possession, physicality), Mathilukal reveals something more elemental: two solitary humans reaching for each other across a barrier, finding poignancy in voice alone.

The Tender Yet Turbulent 2000s

What MT Vasudevan Nair achieves through Oru Cheru Punchiri is a romance that feels at once ordinary and sublime, functional yet profoundly poignant. At the heart of this love story is an elderly couple who have weathered the turbulent highs and lows of life and have now arrived at a space of such unadulterated peace that it almost feels sacrilegious, as a viewer, to intrude upon their quiet joy. Living in a village, immersed in life’s smallest pleasures, they seem to exist in a realm where the world’s anxieties momentarily fall silent. It is a love that has outlived desire and settled into devotion, where companionship itself becomes the highest form of romance.

There is a similar form of companionship in Pranayam (2011), in the relationship between Mathew (Mohanlal), confined to a wheelchair, and Grace (Jayaprada). They are not young, yet not quite elderly either, and within that in-between space, desire still flickers unmistakably. Despite physical constraints, passion lingers: in the way he glances at her, in the faint tremor in her voice when she speaks to him. Pranayam is, at its core, a film about second chances. It persuades you that love, when anchored in something enduring and sincere, can weather any storm, not by avoiding it, but by surviving it together.

When the married Deepthi (Meera Jasmine) falls in love with Economics Professor Nathan (Mammootty) in Shyamaprasad’s Ore Kadal, what lends this ostensibly forbidden affair its rare poignancy is the film’s carefully non-judgmental gaze. If Deepthi feels newly alive after years of emotional abandonment within her marriage, Nathan, too, after an initial resistance, finds himself swept away by the relationship’s almost destructive intensity. Their relationship is neither glorified nor condemned and is allowed to exist in all its fragility and contradiction. So when Deepthi reaches out to Nathan in the end, what one feels is not moralistic disapproval, but a lingering, complicated empathy, for loneliness and the human desire to feel seen.

The volatile intensity of Contemporary classics

It is difficult to think of a romance as inherently melancholic, stirring, and self-destructive as the one between Mathan (Tovino Thomas) and Appu (Aishwarya Lakshmy) in Mayaanadhi. If Mathan has always operated on the wrong side of the law, Appu has, over the years, endured and forgiven him in cycles. Each time he strayed, she would detach; each time he returned seeking absolution, she would allow herself to be won over again. Even amid the everyday humdrum of their separate pursuits, they kept circling back to one another, through snubs, arguments, bruised egos, and silences. In Mayaanadhi, it is a tragedy that ultimately immortalises them. And yet, strangely, one is left with the feeling that theirs is a love too restless to end, as though it might seek reunion in another lifetime.

When the mute Ameer first lays eyes on Akbar as he flagellates himself during the ritual of Kuthu Ratheeb, Moothon stages a moment that feels at once spiritual, earthly, and quietly seismic. Thus born is a love story marked by defiance, a romance that is already conscious of the boundaries it will be forced to confront. If Ameer’s silence makes his longing more luminous, Akbar, who is caught between faith, fear, and desire, gradually finds himself disarmed by a connection he can neither name nor resist. The film grants it the same emotional legitimacy as any other romance, shaped by vulnerability, yearning, hesitation, and surrender. And perhaps that is why, when the story bends toward tragedy, it wounds with such quiet force. We are not mourning an act of rebellion; we are mourning a love that felt deeply, irrevocably human.