His Perfect Days: A Conversation With Wim Wenders

The acclaimed 78-year-old director speaks with Ishita Sengupta about the reasons for making his latest film, Perfect Days, the lessons he took back from the experience, and his relationship with time

Last Updated: 07.36 PM, Apr 28, 2024

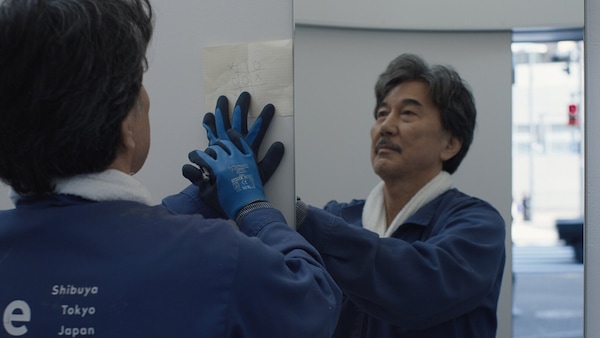

IN WIM WENDERS’ Perfect Days, the protagonist has a perfect day, every day. Hirayama (Kōji Yakusho) is a toilet cleaner in an upscale neighbourhood in Tokyo. Every morning he wakes up at the crack of dawn, cleans his room, wears his uniform and leaves for work. But there is a decorum to this tedium, a commitment to this pattern that elevates it from the folds of monotony. Hirayama likes what he does. He likes cleaning his room, watering his plant, having his morning coffee on the way, and listening to Lou Reed as the sun shines on his face. There is a rigour to this likeness, reflected even when he cleans toilets. His vehicle is filled with an arsenal of cleaning equipment which he uses to scrub and toil; this attentiveness is only interrupted by efficiency as he pauses midway to pull out a magnifying glass and check if he has cleaned well.

Hirayama’s striving to not leave a mark qualifies for work ethic and doubles up as the purpose of his existence. He is a man of few words. He does his work, takes lunch breaks in the park, clicks pictures of trees with his film camera, and goes home. Hirayama keeps to himself with such intent like he is bent on not exerting his presence. Yet, there is something timeless about him. The protagonist in Wenders’ new film represents a way of life, simple but not simplistic, that feels anachronistic. His desire to take pleasures in little things in a world imbued with maximalism feels rebellious.

Perfect Days is a hypnotic film that emerged from a series of circumstances with the dramatic arc of a film. In 2022 Wenders was invited to Tokyo to take a look at the city’s public toilets designed by renowned architects like Tadao Ando and Kengo Kuma, and hopefully make a film on them. The filmmaker used this as the starting point to reimagine days in the life of a man who cleaned toilets for a living and preserved solitude for sustenance.

Wenders co-wrote the film with Japanese novelist Takuma Takasaki and shot it in 16 days. In 2023 it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and the next year it was Japan’s official entry for the Oscars (the first by a non-Japanese director). Perfect Days dropped on MUBI India on April 12. On that occasion, the 78-year-old director spoke to this correspondent about his reasons for making this film, the lessons he took back from it, and his relationship with time. Edited excerpts from the conversation.

Perfect Days centres on a man who is a toilet cleaner and is attuned to the little joys in life. He listens to music from audio cassettes and reads physical books. Hirayama occupies an analogue existence in a digital world. What does making a film like this mean to you at this stage in your life?

Perfect Days was a real gift because it took me back to my beginnings. Hirayama is a man of reduction and leads a simple life. I knew I could not make a fancy film on him. So I decided to go ahead with the most simple way possible: with a cameraman and a camera on his shoulders. There was no tripod, no steady cam. The process had to correspond to his simple life. The relationship to the main character dictated the rhythm and the ideas and eventually, he became the film.

Making the film in the oldest tradition was very healthy for me. It was healing and simple and it turned out that simplicity is not always easy but it is good for the soul. And it was good for the relationship with the actor and myself. Kōji, Franz Lustig (the cinematographer) and I became very close. After a few days we felt that Hirayama, a fictional character, had become a real person and we were just following him around. Like we are making a documentary.

For the first couple of days we were rehearsing but I thought that if I could just record the rehearsal. So after a while I proposed that to Kōji and he was amazed. “Well if you think so,” he said. We then went to this mode where we never shot for more than one take because it felt so real. We were making a simple film with simple creative decisions. His philosophy became our philosophy.

You have a thriving career as a non-fiction filmmaker — Anselm, the 3D documentary on German sculptor Anselm Kiefer also premiered at Cannes last year — which, in my mind, ties to the way the routine in Hirayama’s life is shot. It feels like a ritual.

Ritual is the key word because it is ritual. When we were writing the script we realised that our film is very much about the routine of this man. When you are a public servant you have a routine. But it is so often considered a negative word. Routine is not something one aspires to have; it is something you want to get behind you.

But Hirayama approaches his life — wakes up, goes out, looks up at the sky — like it is the first time. He does his work in a ritualistic way… that is why I liked that you used the word. He is like a craftsman who makes every object, and each time it is anew. Hirayama cleans toilets like each time it is a new task. There is a routine but there is also immense freedom, something we realised the more days we lived with him. We started to enjoy his life and almost became a little jealous. That jealousy remained with me and that is the biggest lesson of the film that there is something that can rub off from Hirayama to your own life.

Hirayama is a man of few words but the authors he reads (Patti Smith, Aya Koda) and the musicians he listens to (The Velvet Underground, Lou Reed) lend a rich inner life. Can you talk me through the process of choosing them?

When I was writing the script with Takuma Takasaki, without whom I couldn’t have done it, I sensed that we have a man who does not talk much. He talks to people he likes, like his niece, but generally he doesn’t do small talk. For a man like him, the books he reads and the music he listens to can be very telling.

At first I was very shy about using my own musical taste. But Takuma reassured me that they listen to the same music in Japan as we do in Germany. Much like us, they too are living with a substitute American culture right over them. Then I wrote all the songs which felt right and it became a big part of the storytelling process.

Male characters in your films are often tortured beings. Even the angels are not spared the misery. In comparison, Hirayama’s contentment feels almost defiant.

In a strange way he is a counter-culturalist. He lives on his own terms. He probably did live a different life before he became a toilet cleaner. You sense that when his sister appears. Hirayama was probably wealthy but he was also dissatisfied. And that is what compelled him to make a radical change in his life. When we see him, he is living that change and realising how good that is for him. He is no longer living a life that is determined by anyone else, which probably was the case when he was rich. The entire crew, especially me and my cameraman, felt happy to be in the presence of such freedom. We felt freer than ever making this movie even if it was just 16 days.

This is your first fiction film in Japan.

Japan has always been close to my heart. The first time I was here was in 1977, an eternity ago, felt like homecoming. Over the years I stopped counting the many times I have come here. When I got the letter of invitation to visit Tokyo and discuss the project, I realised I was homesick. It was so nice. They said if I don’t like it, I don’t have to do it. But I was inspired in a different way and was moved by the respect with which the people here treated the parks and the toilets during the lockdown. The common good was more precious than the personal good. Sadly, this was not the case in my city, Berlin.

You are 78 years old and in the sixth decade of your career. What is your relationship with time?

My relationship with time is that it is not worth spending on routine. It feels short and useless if I do something only because I know how to do it. But time becomes long when there is something challenging to do. Like, making Perfect Days was challenging to do, so was Anselm. Time is relative to the amount of curiosity one has for that time.

Wim Wenders' Perfect Days is now streaming on MUBI.

Subscribe to our newsletter for top content, delivered fast.