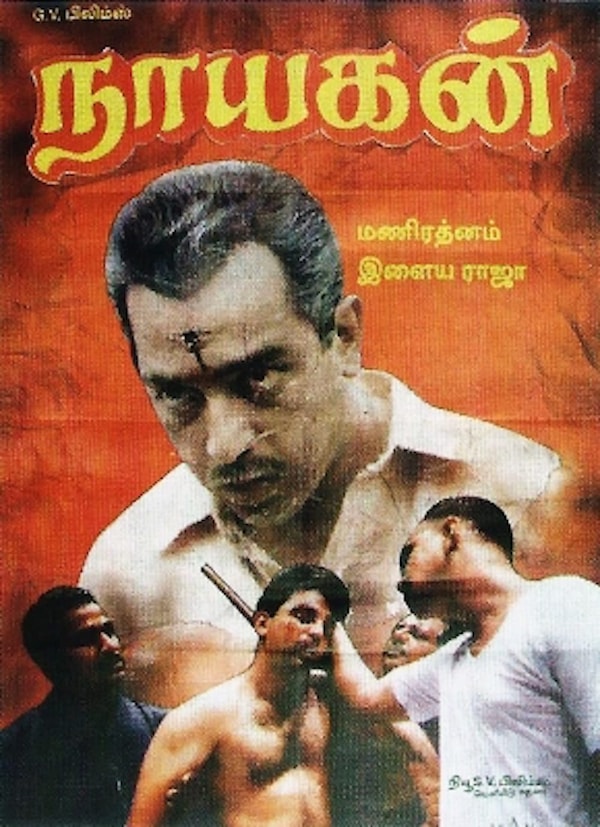

35 years of Nayakan: How the Mani Ratnam-Kamal Haasan film changed Tamil cinema for the better?

Nayakan was a Deepavali release in 1987 (October 21). The Kamal Haasan-starrer elevated Mani Ratnam's stature, as a filmmaker.

Last Updated: 08.35 PM, Oct 22, 2022

When Pa Ranjith's 2018 film Kaala came out, it was compared to Mani Ratnam's Nayakan (1987). Given that both of the stories were set in Dharavi (Mumbai), besides many other similarities, this was natural. Additionally, since the 1980s, Kamal Haasan and Rajinikanth, two rival actors, have consistently been compared in their respective careers.

Kaala is a revolutionary film with a Superstar front and centre. You will be startled and perhaps, even let down if you watch the movie, anticipating the typical Rajinikanth hoopla. In Dharavi's densely-crowded slum, Kaala's backdrop chiefly highlights Tamil immigrants from decades before surviving in unclean, unsafe, and inadequate living conditions. Karikalan, known as Kaala, resides there with his family and has long been regarded by the slum inmates as their saviour, leader, and supporter. The movie is about the protagonist's and his people's struggle for land with the adversary and the consequences they endure.

Like all epics, Nayakan begins and ends in tragedy. The Kamal Haasan movie scores high on storytelling, scripting, and cinematography while also having a strong recall value. What makes it a classic, though? You just need to see one Mani Ratnam movie to recognise his brilliance or at the very least, to empirically gauge the magnitude of his lasting influence on Indian cinema. And, Nayakan could be THAT film.

Young Velu Naicker mistakenly leads the police to his father and witnesses his death at their hands. Naicker, who is filled with remorse and rage, stabs the police officer in self-defence before fleeing to Mumbai, where he is fostered in Dharavi by the benevolent small-time smuggler Hussain.

In Nayakan, Kamal Haasan's character develops into a full-blooded 'don', although he still adheres to his father's principles of serving others. I saw The Godfather before I saw Nayakan. Therefore, the latter had a greater effect.

Velu Naicker is empowered by a forced maturity that has been placed upon him after killing someone at such a young age. Even in a brutal environment, he recognises the possibility of decent behaviour. He is detained and subject to torture by the police after he requests better money for a modest task he completes on Hussain's behalf. The unabashed clash of languages and cultures is on display as Naicker receives criticism for being an outsider. Anything carried out for the benefit of others is right. Velu Naicker and Karikalan adhere to the same philosophy.

One can never judge if Kamal Haasan's character is good or bad. Naicker becomes Nayakan (Hero). And, Karikalan is the Velu Naicker in Kaala.

Kaala could reasonably be referred to as Rajinikanth's Nayakan. But, the more one looks beneath the surface of both of these films, the more we see how opposite they are.

Kaala shows a real struggle against oppression, one that Dharavi slum residents endure against fascists. The result is inspiring; the portrayal of oppression is authentic and the acting by the majority of actors is faithful to the characters. The music by Santhosh Narayanan enhances the charm of Rajinikanth and complements the story, but what I liked the most was how completely direct the story is, with no soft touches, which is again typical of Pa Ranjith. Yes, I did appreciate the film since a victory over fascism is a victory for all of us. The movie's ability to weave all of this into a contentious story, though, is truly astounding.

One of Kamal Haasan's best performances is in Nayakan. Don't forget about PC Sreeram's fantastic shots, either. Each of them is a frame inside a frame. But if you pay close attention to those, you'll notice that the movie is a collection of shots. You can tell that these people were still being crushed by their circumstances, fate, or whatever else.

Every change in Velu Naicker's life is followed by an actual incident, which makes Nayakan more realistic than Kaala. After the father dies, Velu moves to Mumbai. A man evolves better once he decides on the ideology that will guide his life. Every stage that Kamal Haasan's character goes through is perfectly captured by Mani Ratnam; be it his wife's passing or his daughter's separation.

One of the first movies to show that a star need not always be the focus of a movie was Nayakan. The Mani Ratnam film avoids using cliches, but finds ways to reinvent the old, giving it new meaning and purpose as well as, more significantly, a new identity, much like its hero. Kaala pans out the same way, too.

Rajinikanth plays his age; he is even a grandfather in the film as he is in real life. Lenin is the name of Karikalan's younger son; the subtext is infinite. Even Huma Qureshi, a Muslim from Pathamadai, has a complicated past that most people in Tamil Nadu will be familiar with. And a brilliantly-planned masala tale has everything. What is there to dislike? The tension that the movie builds up over the majority of its running length, together with a deft utilisation of Rajinikanth's aura, keeps the movie cohesive.

But, Kaala has problems and is occasionally inconsistent. It might have benefited greatly from a thorough overhaul. It is brave and timely at the same time, putting a star at the centre of its narrative, posing all the appropriate questions, and smashing innumerable preconceptions. In the end, Karikalan returns in a riot of colour.

Kaala has a lot of theatrical moments: Rajinikanth dismounts his bike. His cheeks clench, his muscles tense, and his brows twitch with danger. When he is about to engage the approaching villains, reinforcements unexpectedly encircle him.

To depict the stories of actual individuals who fight daily battles for survival, Kaala recreates one of our last larger-than-life superheroes on screen. And, is it possible to conclude that Rajinikanth himself was attempting to spread the message not to muddle his politics with his films? I don’t know.

Karikalan doesn't engage in a significant fight in Kaala until almost the end of the first half. Naicker, again, isn't your typical don, mind you! However, better scripting would have taken Kaala to remarkable heights.

The narrative of Karikalan and Zareena (Huma Qureshi) seems hurried and awkward. Those scenes involving both fail to gel with the screenplay and come out as a cheap attempt to appease the masses. Here, Nayakan scores better. Even now, 35 years later, you may still smile to yourself when you watch the romantic scenes involving Neela and Velu Naicker.

Ranjith utilises Rajinikanth as a prop to convey the story of Dharavi and its residents, much as how Mani Ratnam used Dharavi in Nayakan to tell the life of a single hero, Velu Naicker. The other two heroes of Kaala are cameraman Murali G, who specialised in the colourful climax, and art director T Ramalingam, who replicated Dharavi in Chennai.

Ranjith does, however, make an important point in Kaala when he shows how his protagonist is the exact opposite of Nayakan. Am I good or bad is the existential dilemma that the protagonist of Nayakan struggles with. Mani Ratnam forces the main character's grandson to ask him this question in the climax. Ranjith, on the other hand, acknowledges that Kaala is a democratic leader of the radical people, who doesn't engage in criminal activity to help people, unlike Naicker.

Although, Rajinikanth wasn't the only Kaala, there is only one Nayakan. Every face in the terrifying maze known as Dharavi appeared to be a Kaala as they went about their subhuman lives. The Pa Ranjith movie scored quite a lot here.

The aforementioned contrast is not the end of it. Ranjith even flips a scene from Nayakan to start his finale sequence. In Nayakan, a small child enters the frame and dabs colour over Velu Naicker's face as he approaches a group of people eager to celebrate Holi. In Kaala, a small girl throws black coloured powder over Hair dada’s face to start the superbly planned, vibrant climax. Ranjith does everything possible to oppose Mani Ratnam's Nayakan and declares, “Unga hero, ennoda villain!”

The way Ranjith flips the conventional good/bad paradigm is what makes it interesting. Hari dada (Nana Patekar) swears by the Ramayana; wears white and has a Ram statue conspicuously displayed in his living room; even has a white sofa set in his home. (Hari, which is another name for Lord Vishnu, clearly reflects some consideration.) In contrast, Hari dada refers to Kaala as Raavan because he always wears black. Hari dada, who thinks he is Ram, is defeated by Kaala, who also refers to himself as Yama and who is this Yama—an abstract Karikalan—in this story.

The story of the Dharavi slumdog hero doesn't often mesh well with Rajinikanth's brash language. Karikalan rejects Hari dada's notion to make Dharavi more beautiful, but what is Karikalan's suggestion in its place? Kaala supports the right of the public to protest but offers no specific recommendations for how to move forward.

In the meantime, Kaala's producers were sued by Mumbai-based journalist Jawahar Nadar, who sought Rs 100 crore in damages and demanded that his late father, S Thiraviam Nadar, be acknowledged as the film's inspiration in some way. Jawahar asserted that Kaala was based on the life of his father, a revered figure in the Mumbai neighbourhood of Dharavi where the movie was filmed.

So much so that Kala Seth, the nickname given to the late Thiraviam Nadar by the Dharavi community after he became successful in the jaggery industry, is directly referenced in the name of Rajinikanth's character in the movie, Kaala.

Tamil cinema continues to celebrate this kind of movie and may do so in the future. New directors are likely to enter the industry and create more cult classics.

Mani Ratnam probably had no idea that he was paving a difficult path to fame when he made Nayakan in 1987. The film completely changed Kamal Haasan's career trajectory. Movie buffs were treated to a never-before-seen experience that chronicled a gangster's life. The business gained access to a wider market; as a result, the 'Nayakan' effectively transformed into 'Ulaganayagan'.

The rest of India was impacted by the Nayakan model. Every other industry tried it and found success with it. Every superstar, including the ones in Bollywood, wanted to be the don who ruled Mumbai. Then, Suresh Krissna's Baassha happened.

Now that the heroes of Tamil cinema had two options for getting to and controlling Mumbai, the never-ending Bombay-ka-Baassha narrative from Kollywood began. Nayakan served as an inspiration for many other filmmakers to create underdog narratives, including Ajith's Jana, Billa 2, Mankatha, Vedalam, Dhanush's Vada Chennai, KGF: Chapter 2, Pushpa and Simbu's Vendhu Thanindhathu Kaadu.

Even Thalapathy Vijay wasn't spared from the 'don'-driven films. Thalaivaa (2013) was a spiritual sequel to Nayakan. To save, indeed, the Tamil community, Vijay assumed the role of Vishwa Bhai and rose to prominence in Dharavi. In the middle of these, Suriya experimented with Anjaan's Baashha template (2014), too.

The genre of gangster movies is not new to Tamil cinema, and the films' critical and financial successes have shown that audiences are still interested in them when the plot is compelling and the acting is top-notch. The path of the anti-hero/protagonist is distinct in each film that has ever been created, and the surroundings vary each time, which is what makes this genre of Tamil films interesting.

Consider the Vikram Vedha of Pushkar-Gayatri. The good-looking cop, Vikram (Madhavan), seeks to apprehend the gangster, Vedha (Vijay Sethupathi), who is perceived as “evil”. We wonder if good can be evil and vice versa as a result of their interactions and the kind of relationship they form. The movie was remade in Hindi with Saif Ali Khan as Vikram and Hrithik Roshan as Vedha.

Here’s an important question: Is it true that Tamil viewers prefer to see their favourite actors in villainous roles? The majority of the gangster characters that have been written for films in Tamil are not all black or completely bad, but rather come in a range of grey colours. Due to external factors, they become worse, take tremendous measures to safeguard their family and perform nice things for those who are less fortunate or in need.

In many cases, the gangster changes in the end and accepts responsibility for his deeds. The crowd seems to prefer the redemption concept, even though this may be truly cinematic. Movies also contain an inherent love tale or romance in which the anti-hero falls in love with a woman who may be harmed as a result of the adversary and then seeks retribution. The audience is greatly moved by the emotional theme of fighting for someone you love in these movies.

Aaranya Kaandam, Jigarthanda, Jagame Thanthiram and other gangster movies have all been recognised as landmarks in Kollywood. This not only demonstrates the calibre of Tamil cinema's directors but also how gangster movies can adapt to the times while maintaining a strong sense of place.

Every movie is a visual story, and any tale with a common topic can appeal to people all across the world. However, the quality of the production is equally crucial. Making movies sometimes requires making huge investments, therefore producers must be willing to take big risks. In contrast to Bollywood, producers all over the south lack substantial pockets and easy access to significant funding.

With the release and popularity of South films in Hindi across North India over the last two years, doors for south cinema have opened up; thanks to the phenomenal expansion of OTT platforms and the seemingly-insatiable desire for material for the digital realm. At the end of the day, movies need to be entertaining, and as long as they are, audiences will visit theatres, whether they are in Hindi or another language. It's time for moviegoers to take charge and broaden their horizons by watching a variety of films rather than relying just on well-known actors.

Tamil Nadu, like every other state in India, is rife with tales waiting to be told, and the differences in the state's culture, vocabulary, and traditions only add to the excitement of the movies to come, as fresh anti-heroes redefine good and evil along the road.