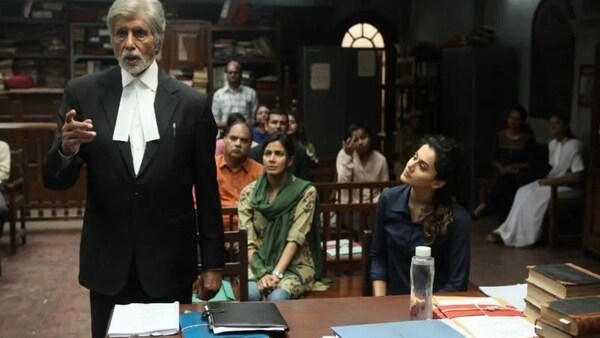

As Pink turns 5, investigating how the Amitabh Bachchan, Taapsee Pannu film kickstarted the discourse around consent

Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury’s courtroom drama Pink, which released in 2016, wasn’t just another social film. For the first time, a mainstream Bollywood film was addressing consent.

Last Updated: 07.54 PM, Sep 16, 2021

It took an Amitabh Bachchan to declare “no means no” for Bollywood to sit up and take notice of their blatantly patriarchal conditioning. Sure, Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury’s 2016 legal film Pink had the male saviour complex play out like many other ostensibly women-centric films such as Padman (2018) or Mission Mangal (2019), but for the first time, a mainstream Hindi film with A-list actors explored the idea of consent without blatantly vilifying the men.

But cinema does not exist in a vacuum. It is created within a socio-political context that dictates its perspective. The pre-2000s mainstream films, especially comedies and romances, vehemently normalised male predatory behaviour. Take for example, Mani Ratnam's sweeping 1998 romantic drama Dil Se. Shah Rukh Khan’s Amarkant Verma stalks, intimidates, ambushes and slaps Meghna (Manisha Koirala) in an attempt to convey what he feels is adoration. He also sneaks a look into the bathroom while she is inside - an act a 21st century viewer would instantly recognise as violating and voyeuristic.

A blockbuster of 1990, Madhuri Dixit and Aamir Khan's Dil starts off as a breezy college romance, only Madhuri is told in jest, “Aj Na Chorenge Tujhe”. This banter continues outside of songs too, and most often, sees the woman being ridiculed. In one scene, Raja (Khan) abducts and threatens Madhu (Madhuri) with sexual assault to prove a point. He indicates he can violate a woman if he chooses to, but he won't because not doing so gives him a moral high ground. (Yes, sarcasm!) But instead of being enraged at his audacity, Madhu falls in love with Raja. Later in the film, the two elope together and after a few road bumps, live happily ever after.

Debuted one decade later, Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein (2001), is perhaps the most fitting example of endorsement of a misplaced sense of masculinity. A post #MeToo reading would prove Madhavan's character to be a serial harasser. He lies about his identity to a woman to attract her, and those frequent bouts of anger he projects on his friends, enemies, beloved and father, are justified as passion.

Despite its overarching theme of friendship, Mujhse Dosti Karogi (2002) saw a similar pattern being repeated. After a mistaken identity shtick, the hero and heroine finally find their way back to each other. But two and a half crises later, the heroine is rid with guilt and pity, and refuses to pursue her relationship. But respecting boundaries isn't a sign of all-consuming love (again, sarcasm!). Thus, the hero proceeds to arm-twist (yes, literally) the heroine into confessing her love for the hero. But obviously, all's well when 'miya biwin raazi' to tolerate and foster toxic behaviour.

On instances where predatory behaviour was not valourised, it was othered. Only a man who can scour open his chest with a sharp blade, gape at pictures taken surreptitiously on a projector screen, and gate-crash a party to eliminate competition can exhibit misogynistic behaviour. It was either Shah Rukh Khan in Darr (1993) and Anjaam (1994), or Nana Patekar in Agni Sakshi (1996), or nothing. That the same man lay down on a woman's lap without her consent, or tore her clothes in Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jaayenge (1996) blithely escaped from under the patriarchy-tinted glasses.

On instances where predatory behaviour was not valourised, it was othered. Only a man who can scour open his chest with a sharp blade, gape at pictures taken surreptitiously on a projector screen, and gate-crash a party to eliminate competition can exhibit misogynistic behaviour. It was either Shah Rukh Khan in Darr (1993) and Anjaam (1994), or Nana Patekar in Agni Sakshi (1996), or nothing. That the same man lay down on a woman's lap without her consent, or tore her clothes in Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jaayenge (1996) blithely escaped from under the patriarchy-tinted glasses.

The post 2010 cinema witnessed a shift in the depiction of male protagonists, as hyper-masculinity started being replaced with compassion. Despite a film centering around sperms, Khurrana's portrayal of Vicky as a sensitive, un-macho man ushered in a new era. Curiously, the film also featured persistent pursuing/stalking as an acceptable mode of communicating love. What Anu Kapoor’s Dr Chadda did with Vicky, Vicky did with Ashima (Yami Gautam). Yet, while the former was evidently ridiculed, the latter was - you guessed it right - accepted with open arms.

Films like Raanjhanaa (2013) and Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016), while recognising problematic behaviour of their male protagonists, proceeds to imbue them with heroic characteristics, and most often, by the end absolve them of their deeds. Kabir Singh (2019) may have suffered the brunt of cancel culture by hailing an abusive man-child as desirable, but Ae Dil Hai Mushkil killed off its female protagonist, almost to indicate that she is relevant to the narrative only until she is relevant in the hero’s life. Her only fate, after scorning the hero, is death.

Before Pink spelt out those words – no is no – with razor-sharp precision and emphasis, Sudhir Mishra’s Inkaar (2013) (meaning refusal) squarely addressed the complexities of gender politics in a workplace dominated by men. It veered into ambiguous territories, like having former romantic associations with one’s perpetrator, the ramifications of speaking up against a system designed to benefit the powerful, and dealing with labels such as “difficult to work with” and “bitter.” It also explained why one cannot assume consent, once given, is a free-pass to be used as per convenience.

Ekk Main Aur Ekk Tu (2012) touched upon consent briefly at the wee end of the film, when Imran Khan’s Rahul mistakes Riana’s (Kareena Kapoor Khan) friendliness for love, and darts forward to kiss her. When Riana is taken aback, Rahul is scorned. Later, after a pep-talk session about misreading signals, Riana and Rahul resolve their differences. But the story sees Riana apologising to Rahul for “leading him on,” thereby ultimately placing the blame on the woman by questioning her conduct.

The post-Pink era has seen several films and shows that addressed casual and overt sexism. Thappad (2020) was heralded for bringing to fore multiple stories of microaggression inside a household. Soni (2018) saw two women bond over a shared sense of alienness in a male-dominated profession. Delhi Crime reconstructed the 2012 gang-rape case with nuance, sensitivity and empathy.

But commercial Hindi filmmakers don’t always get it right. In Section 375 (2019), a man laments about false accusations and how often women resort to lies to exact revenge from past lovers. False accusations aren’t unheard of, but it leads one to question why a movie about a woman executing her mammoth revenge against a man would not narrate the story from the woman’s perspective. Too many logical loopholes tend to prove that a story is written with a decisive conclusion in mind. Thus, despite an intriguing premise, the film seems all too eager to establish the wrongdoer and the wronged with scales always seemed to be tipped in one’s favour.

Hence, when Liar is adapted in Hindi as Marzi (2020), the show seems unsure about navigating victim-blaming, bullying, slut-shaming, gaslighting or social stigma, instead turning it into a twist-heavy revenge drama. Netflix’s Guilty (2020) mcharted similar waters, as a woman’s account of sexual harassment is dismissed by her peers because of her closeness to the perpetrator. But the film’s superficial and synthetic treatment never let the audience sink their teeth deep enough into the story or the individual characters’ journeys.

Nonetheless, it is a start. However faulty they might be, a Guilty is a step forward from breaking into “Haseena Maan Jaayegi”. These new breeds of films are reflective of our collective reckoning of misogyny perpetuated since the beginning of time.

Premium

Premium