Bheed Is A Compelling Archive Of A Human Tragedy

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative over new Hindi films and shows. Today: Bheed.

Last Updated: 06.28 PM, Mar 25, 2023

THERE’S SOMETHING called “an Anubhav Sinha film”. The specification speaks less of the filmmaker’s signature and more of his insistent filmmaking. With Mulk (2018) there was a definite shift in his oeuvre which has only become more defined with time. Sinha’s focus on social malaise is so obdurate that the fixation has evolved into a parameter of its own, hinting at both his limitations and flourishes. His previous outings reveal his blindspots: a tendency to be obtuse (Anek, 2022); prioritise theme over treatment (Thappad, 2020); and more crucially, lean on saviours for intervention (Article 15). In that sense, his latest film is cut from the same cloth and yet unfolds as a departure. People here are not striving to be heroes. Instead, given the times they are in, the attempt is to be less of a villain.

Bheed, as a voiceover by Manoj Bajpayee conveys, is set in the early days of the pandemic. A new virus called COVID-19 is rapidly spreading and the government has mandated a total lockdown overnight. Modes of transport are ceasing to operate and social distancing is becoming the norm. In the midst of this, migrant labourers are making their way to villages. Their citified workplaces have closed doors on them. The trouble is the hasty, uncaring political decision has also distanced them from reaching home. Bheed chronicles one day among the many in the lockdown when migrant labourers were stranded in the middle of nowhere; the inhuman way they were treated reduced them to an inconvenient crowd from a group of helpless people.

Given the way Sinha is prone to tell a story, which often comes across as an informed man talking down to his peers, there was plenty of space for Bheed to become a Twitter thread. Which is to say that his angst to retell the horrors of what happened could have hijacked the need to remind who it happened to. Besides, when recounting something as traumatic as the pandemic, hindsight is not as much of a benefit as it is an impediment. For, things only got progressively worse.

The impressive bit about Bheed is that it unravels with an admixture of confusion and rage that approximates the chaos of that time. One was prescribed to wear masks but it hadn’t become a habit yet. Fever was not yet considered a telling symptom of the virus. Hospital beds were occupied but the cries of help were not pouring in. Orders were changing with every announcement. The government had closed the borders but its apathy towards a certain section of the society was not yet apparent. It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times.

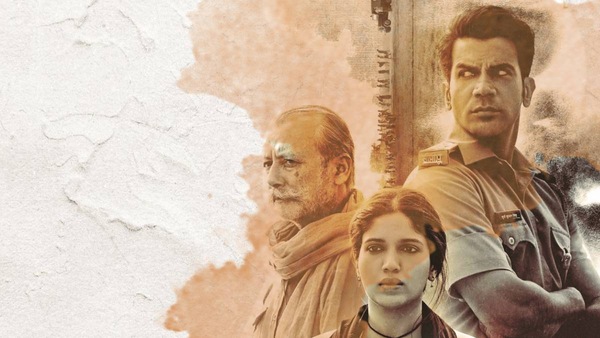

SHOT IN BLACK & WHITE (the style does not become pretentious), Bheed takes place mostly on an afternoon at the check post between two states. In the event of a lockdown the border was sealed. This arrangement, a sudden halt on the road, brings forth people from all stratas. There is a lower-caste police officer Rajat Kumar Singh Tikas (a reliable Rajkummar Rao) who is in charge of maintaining peace. There is Renu Sharma (Bhumi Pednekar), his partner and a doctor, who represents one of the frontline workers. There is a privileged woman (Dia Mirza) who needs to reach her daughter’s hostel before her estranged husband does. There is a journalist (Kritika Kamra) trying to do the right thing. There is an upper-caste Hindu man (a gripping Pankaj Kapur) who worked as a watchman but told people in his village that he was in security. Even Tablighi Jamaat is alluded to.

While such inclusions might look like tokenism, Bheed (written by Sinha, Saumya Tiwari and Sonali Jain) never comes across as surface level representation. Part of the reason being the film is telling a story we are acquainted with if not conversant with the details. Even if things had not unfolded entirely like this, enough time has passed since then to confirm that, in some capacity, they had. Such clear-eyed writing also ensures that the many issues it tackles do not stick out as thorny. Sinha touches upon caste, class, privilege, all within less than two hours. They do not seem extraneous because Bheed, at its core, is telling a unique India story, one that is entrenched in the social fabric of the country. The compelling rootedness of the outing also ends up critiquing the left and the right gaze. When the Kritika Kamra character, a liberal, educated woman, asks Rao for a byte on the way Muslims are being treated by the Hindus, the latter, a lower-caste man attuned to being the recipient of prejudice, retorts that disenfranchisement is not limited to religion. Sure, the presence of a mall, a stand-in of excess in the time of crisis, near the post is too literal a metaphor but some tales of disparity need the crutch of symbols.

Having said that, not everything works. The opening scene feels particularly laboured, with people spelling out the obvious. There are some instances where Sinha is being himself and assumes a morally superior position. Like when Dia Mirza’s character talks to her daughter over the phone and emphatically states that people like their driver have better immunity. “They do not have lactose intolerance or migraine”. Or when a journalist looks outside his car’s window and unironically states that he loves the incredible India. I understand the intent is to underline the blindspots of privilege but in a film that shows more than it tells, these moments do not really sit.

I’d still argue that the most affecting achievement of Bheed lies in uncovering the distinct nature of lockdown, in purporting that at the most fundamental level, the act was a depiction of cruelty, a naked expression of power more than an upshot of necessity. We don’t see the faces of any minister. The Prime Minister is not mentioned nor is his announcement of lockdown included (the trailer did have that bit). But these forced omissions speak more in their absence than they would have in their presence. We all know what happened and how. Newspapers have the details. People carry the scars. But we needed an archive of the tragedy. Bheed provides that.