Dallas Buyers Club: Examining Matthew McConaughey, Jared Leto’s underdog tale 7 years since release

Dallas Buyers Club, released in 2014, does not claim to be a definitive guidebook on AIDS treatment. It’s an understated celebration of less-than-perfect life.

Last Updated: 09.27 AM, Nov 22, 2021

Director Jean-Marc Vallée’s Academy Award-nominated drama tenderly wove fact and fiction in the biographical drama of Ron Woodroof, an AIDS patient of the 1980s who revolutionised the treatment of the disease by administering FDA unapproved drugs on himself and other fellow HIV positive patients. Dallas Buyers Club, released in 2013, saw a rawboned Matthew McConaughey effortlessly slip into the role of Woodroof, a foulmouthed, oversexed Texas rodeo rider and a raging homophobe. He is also an unabashed cocaine user, gambler and a generous alcohol consumer. Until one day in 1985, he learns he has only a few weeks to live, after being diagnosed with AIDS. While the premise sounds relentlessly grim and grating, the filmmaker defiantly buoys the film with a raucous humour and a heartfelt tale of friendship in the unlikeliest of circumstances. It subverts the ambit of a typical illness/death narrative by populating the first half of the film with the darkest moments. It is not a comedy, but the setup of a ragtag team of few taking on the pharma giants and the bureaucrats lends itself to an affecting underdog narrative.

For McConaughey, Woodroof was almost a deconstruction of his actor’s earlier career-defining hypermasculine roles in Dazed and Confused and Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation. The film makes no qualms about establishing that Woodroof was a homophobic cis-het man. But when his illness makes him a social pariah, the same man turns a sympathetic gaze on the routinely marginalised. This change motivates him not only to scavenge a cure for himself, but the entire HIV-positive community who do not have the social credibility to source the same treatment for themselves.

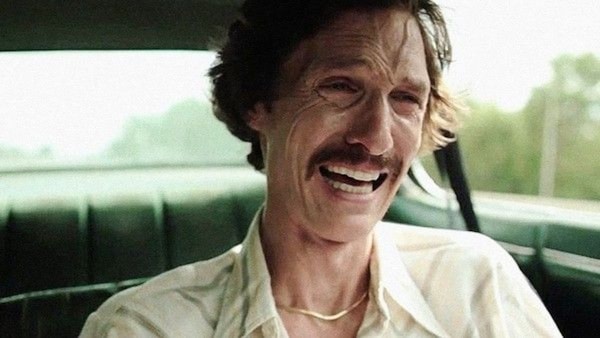

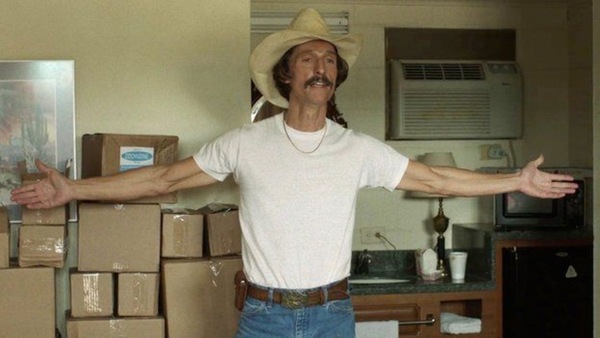

At the time of the film’s release, the most sustained image from the film was McConaughey’s dramatic weight loss. Yet, seven years later, upon rewatching the film, the actor’s physical transformation seems to be the most organic part of the film, as the accidental hero who just wants to live a few more years. Despite his scrawny physical appearance, McConaughey’s charm is infinite as he skips around the hospital with cowboy hats, underwear and a saline drip hanging from his arm. There is no attempt on the filmmaker’s part to scrub off Woodroof’s obnoxiousness.

Woodroof’s journey begins when he realises he’s not responding well to the officially approved treatment, and decides to bypass the FDA to smuggle unlicensed drugs and allocate them to all those looking for a better prospect than a quick, painful and an imminent death. In his journey, he is accompanied by his business partner HIV-positive Rayon (Jared Leto), a transgender woman struggling with a drug problem. Leto pulls out all stops to imbue Rayon with aching humanity and empathy. The character is a bundle of contradictions — she is at one self-reliant and utterly self-destructive. She looks like a statuesque figure in her grand outfits, yet her skin and eyes lack vitality. The character, along with that of Jennifer Garner’s empathetic doctor Eve Saks, were created by the writers after countless interviews with transgender AIDS patients, activists, and doctors. Speaking about the part, Leto once said, "This was a really special movie. I think it was the role of a lifetime. It's one of the best things I've ever done." For McConaughey too, the performance was dubbed his ‘career-best’. Indeed it was. Both Leto and McConaughey took home Oscars for Best Supporting Actor and Best Actor for their respective portrayals of Rayon and Woodroof.

Dallas Buyers Club has a unique, almost documentary style narrative, as pointed out by several critics.The film is sentimental, but does not depend on schmaltz. Neither does the film slip into self-pity and aggrandisement, nor does it milk the plight of its protagonists to sermonise about a different decade. Its matter-of-factly approach is what makes Dallas Buyers Club strike the perfect balance between reality and fiction. It does not claim to be a definitive guidebook on AIDS treatment or even Woodroof’s life — for that, there’s always the 2012 documentary How to Survive a Plague. It does not have its hero belting out fiery monologues about systemic injustices. Instead, it shows how a common cause can often propel the worst of the lot to turn a sympathetic gaze towards the more disadvantaged. In the end, Dallas Buyers Club is an unassuming celebration of less-than-perfect life.