Disney through the years: From a dream merchant of an ill-inclusive world to a culture appropriator?

Charting Disney’s fervent attempt at becoming all-inclusive and ‘woke’. Demystifying the production juggernaut’s sudden need to be relevant and accessible by focusing on multicultural storytelling especially through the recent slate of films.

Last Updated: 12.46 PM, Sep 03, 2021

Among the few happiness-inducing memories that children grow up with, “once upon a time” holds a special place. The phrase propels images of colourful animated princesses running across lush fields of green, giddy with dreams and hopes for the future. Such animation films were steeped with promises of a “happily ever after”, assuring audiences of an idyllic life where little could go wrong.

Walt Disney built this world. Let’s not be like Walt Disney.

Along with its major capitalistic approach towards dream-making and worldbuilding of children’s fantasies, the Disney Corp has been subject to constant criticism. Cultural appropriation and racist undertones have more than defined the juggernaut’s many productions, thrusting conversations on colour and gender back by several years.

However, with the new decade, the company’s policy to expand and become more inclusive has also seen a noticeable shift. In environments that have gradually tilted towards Fascist mores, (especially with global governments taking on a more fundamentalist approach), Disney’s uncharacteristic progressiveness to belt out films portraying various marginalised sections had to be worthy of praise.

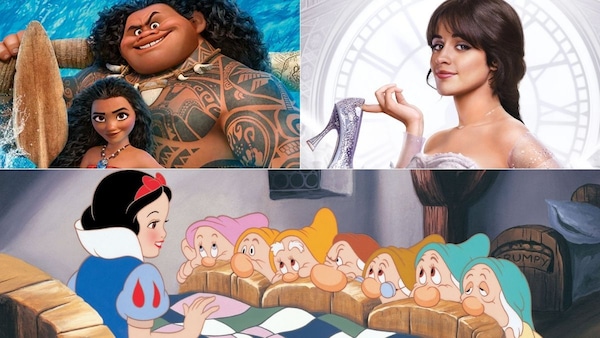

With its recent slate including titles like The Lion King remake, Aladdin, Croods, Mulan, Moana, Soul, Coco, Raya and the Last Dragon, or even the latest release Luca, Disney exhibited a genuine effort to invest in multicultural storytelling. Not only were the films boosted with robust budgets and production costs, they included A-list artists from Hollywood.

Early Disney films like Snow White (1937), Sleeping Beauty (1959), Cinderella (1950) and more recent releases like Beauty and the Beast (1991) and Tangled (2010) may be considered as examples of showcasing “off-centre” cultures. However, the depiction of international women in the films was problematic, with their Frenchness of Germanness starkly compromised in the process of being Americanised. On a similar strain, films like Brave (2012) and Frozen (2013) brought forth the Scottish and Scandinavian milieus for audiences to enjoy but not without its stereotypical treatments.

On a closer look, it’s obvious that the plethora of Disney’s recent films marks the studio’s digital-age tactic to refurbish regionality and corresponding “cultural authenticity” as part of its global “women’s” dogma. A keen example of this is seen in Moana (2016) where the animators continued this indigenous trend albeit with its share of hiccups.

In tandem with Disney’s “glocal” overhaul, the studio announced Colombian-American actor Rachel Zegler’s casting as Snow White in a live-action adaptation of the children’s fairytale. Zegler, an artiste of Polish and Colombian descent, got introduced in a space largely dominated by white actresses. The company even packaged her casting as one of its few watershed moments considering they were trusting a newcomer with a tentpole project.

Additionally, a conscious move to place a coloured actress as a children’s character upheld as “fairest of them all”, was undoubtedly opening up the studio to widespread debates. By positioning Zegler front and centre of a mammoth production, Disney displayed an attempt at making these once-holy children’s tales slightly more accessible to wider sections of society.

Another instance of conscious casting includes R&B singer Halley Bailey coming onboard The Little Mermaid. The Black actress is scheduled to play Ariel, yet another character traditionally portrayed by white actresses.

Almost completing the holy trinity was the news of American-Cuban singer Camilla Cabello playing the friendly cinder-girl in Cinderella. Even though it was not out of Disney’s stable (the film is produced by Columbia Pictures and will stream on Amazon Prime Video), the concept of a coloured popstar taking on the role of Cinderella was novel. This could easily be categorised as a redefining moment where Cabello’s millennial charms would challenge the intrinsic childhood legacy of Cinderella, a fairytale popularised through a primarily white gaze.

Disney is no stranger to social ire and widespread backlash with respect to its earlier insensitivities portrayed in films. Even if (for an instance) we were to put aside films like Peter Pan (1953) and its reckless depiction of the native people or the racist undertones in Dumbo’s (1941) crow and musical number, or even the rude “taming” process that the protagonist in Pochahontas underwent to suit American palates, the production house has managed to go grossly wrong even with their recent releases.

Moana, a film largely packaged as a pioneer in spotlighting the marginalised Hawaiian island community, was wrought with cultural appropriations. For instance, the allusions to pan-Polynesian deity Maui (played by Dwayne Jonson), Moana’s reluctant travel buddy and maritime guide, was filled with erroneous interpretations of the God’s native origins.

After several draft changes, the demigod’s shape was altered from more classically lean, to obnoxiously large (Ito) – a change often hated and condemned by the indigenous communities and scholars as reiterating racist tropes of obese Polynesian bodies. Secondly, the film’s version of Maui was considered simplistic, reductive, and playing into prototypes of a narrow-minded superstitious people, where in actuality, Maui is revered as one of the most intimidating anti-Gods in the Hawaiian religion.

As recently as 2018, Disney came under heavy criticism for “whitewashing” Princess Tiana in Ralph Breaks the Internet. The studio tried making corrective measures by a shoddy redrawing of the character with darker features, months prior to release.

Tiana was in fact the only African-American Disney princess till Beyoncé took up the mantle as Nala in The Lion King’s 2019 live-action adaptation.

After the release of Ralph Breaks the Internet’s trailer, the “Frog Princess” was targeted for what audiences called an unnecessary makeover. Social media erupted with users pointing out how Tiana’s skin tone was noticeably “lighter” with many even mentioning her features to have become “sharper”, something alien to roundish facial traits generally exhibited by African-American visages.

Even though Disney’s present slate promises a serious investment in localised stories, the amateur treatment coupled with a lack of in-depth understanding of traditions prevalent in second and third-tier countries hints at a serious need for intervention.

Many times, less nuanced depictions such as the ones mentioned above widen the chasm between larger sections of audiences and the already-othered, disenfranchised communities that the films claim to represent.

It’s obvious that Disney's universe has indeed promoted psychologically skewered narratives as perfect fiction to impressionable minds for years. Moreover, Disney’s legacy is marred by a systemic exclusion of the “different” if not complete ostracization of them. Thus, its recent and almost sudden need to be ‘woke’ should be judged under the lens of scrutiny.

Notwithstanding the economic profits that Disney stands to make with such global storytelling (what with the marginalised populace’s disposable incomes), the production house needed to uproot its colonial gaze someday. Here’s hoping that this is not just a tokenist stance.