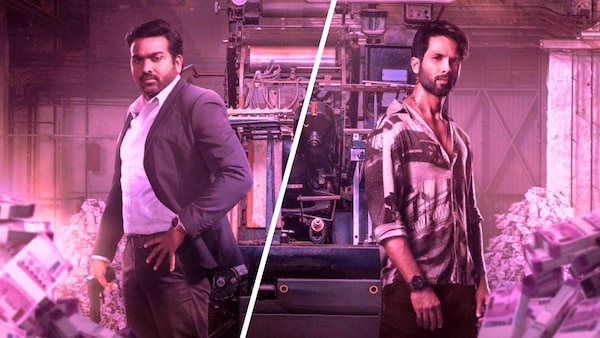

Farzi: In Shahid Kapoor-Vijay Sethupathi Series, A Portrait Of The Artist As A Con Man

Raj & DK transform the cop-chasing-criminal template into something far more nuanced and complex in their latest, Farzi on Amazon Prime Video India. Ishita Sengupta writes.

Last Updated: 09.26 AM, Feb 10, 2023

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative over new Hindi films and shows.

***

IT IS A FAMILIAR STORY. An artful offender is posited against a troubled law enforcer. Both will stop at nothing to achieve their goal. A thin line separates them, not of morality but legality. This is the premise of Farzi, the new series on Amazon Prime. But what is a Raj and DK show without nuance? The overused setting then becomes a shorthand to depict a distinct strata of society, sandwiched between principle and purpose — the middle-class.

Even this would be describing the outing loosely. The filmmakers — who have helmed one of India’s most successful streaming franchises, The Family Man — have a more streamlined vision. Farzi is about a singular section of the middle-class, those who are fated to make a choice between greatness and fame: the gifted ones, the artists. More specifically, it is about the journey of one such artist who refuses to make that choice.

Sunny (Shahid Kapoor) is a painter. He can copy any artwork. His grandfather (Amol Palekar, the erstwhile flagbearer of Everyman in mainstream Hindi cinema) is also a painter and an idealist. The idealism of the old man extends to his profession — he runs a newspaper called Kranti (Revolution). But when did revolution fill one’s stomach? His paper has a dwindling readership. Fairly early in the first episode, he stands to lose his printing press for being unable to repay a loan. Sunny and his best friend Firoz (a terrific Bhuvan Arora), who had met at a railway station in childhood, plan to talk to the moneylender. When they get the leeway of more time, they add up everything they have saved and everything they can sell to pay off the debt. Their eagerness dissipates soon. Sunny, the unacknowledged artist, then comes up with a plan: to make art in the form of fake notes.

Counterfeiting is a faceless crime. In a way, it is not too different from a middle-class existence, which is both faceless and a crime. They are everywhere yet their magnitude invisibilises them. Government policies and expensive restaurants look over them with a similar disdain. Sunny weaponises this anonymity to make fake notes, so perfectly imitated that when the Reserve Bank of India comes up with a machine to detect forgeries (dhanrakshak), his creations bypass it. On the other end is Michael Vedanayagam (Vijay Sethupathi), a police officer obsessed with eradicating this fiscal crime.

Written by Raj, DK and their frequent collaborators, Sita Menon and Suman Kumar, Farzi takes this cop-chasing-criminal template and transforms it into a portrait of an artist bound by circumstances, all the while keenly building up the larger plot of an imminent threat to India’s economy posed by financial terrorism. The shift is so delicate that the execution is a marvel. At the outset, Sunny starts counterfeiting notes to save his grandfather’s press. The first two episodes are aptly titled ‘Artist’ and ‘Social Service’. It is not really incidental. Given how elitist the appreciation of artistry is in India, both these terms make sense when placed together. Sunny’s grandfather had made peace with it. But Sunny is not him. He is a man of his time, politically aware and more socially attuned to the inequality stacked against them. So he takes his angst and art to dupe the system that exists to dupe the likes of them. It is a clever ploy because in one broad stroke, Farzi not only establishes the potency of the middle-class but also, in a perverse way, underlines the indispensability of art. Then Sunny trades his soul. He sells (fake) money to earn money.

Much like The Family Man, where Intelligence Officer Srikant Tiwari (Manoj Bajpayee) is committed to staving off an attack on the country, Michael is confronted with a crisis of a huge consignment of fake notes (₹12,000 crores) arriving in India, which can destabilise the economy. Their characters share more similarities. Both their families are rendered casualties to their duties. Michael is separated from his wife (Regina Cassandra). He has a son. Sethupathi, who makes his streaming debut, is a phenomenal performer but he does something special here. As a Tamil-speaking, alcoholic police officer in Bombay, the actor infuses humour and empathy to a role which on paper, is strikingly similar to Tiwari. Sethupathi not just makes the character his own but uses his deadpan face to enliven even the straightest of lines.

His interactions with the financial minister (Zakir Hussain), irate in a strangely affectionate way, count for the funniest moments in the series, with each throwing expletives at the other with the charm of a compliment. There is a scene where Hussain threatens to fire him in the event of another mistake, using the word “nishkaasit”. Looking down, Sethupathi asks the meaning as Hussain translates the word, heaving with rage. It is a hoot.

So much of it is also achieved by the lines they get to say. Raj and DK are known for their acute awareness of the milieu they depict. There is a rhythm in the dialogues, extending even to profanities. In Farzi too, the dialogues sing. It is a wordy show and the lines (Hussain Dalal is credited for the Hindi dialogues) do most of the heavy-lifting. Ever so often, the risk of representing a class transpires in reducing it to cliches. Recently the Hotstar show Taaza Khabar (incidentally also written by Hussain and Abbas Dalal) did the same. Farzi unfolds, informed with the place and people it is portraying.

The mention of place is crucial because the director-duo’s latest work is a distinct Bombay story as much as it rankles with the universality of have and have-nots. The series not just spotlights the duality of the city, in which it grants space to everyone but makes space only for a few, it also includes the striking nature of Bombay in little details (Pankaj Kumar is the cinematographer). Take for instance how Sunny refuses to have pav, the city’s popular street-food, the moment he makes money. Or, the way ships and traffic jams are used to move the narrative forward. Dingy quarter bars are Michael’s daily hang out spots.

Across the eight episodes, each an hour long, the filmmaking is uniformly tight. Even without the many chase sequences, several moments in the series evoke a sense of thrill for the way they are designed. A dinner table sequence between two lovers pulsates with the uneasiness of impending doom. The assuredness is nowhere more visible when humour finds its way in the most unlikely of situations. Even in the most crowded of episodes, the flow is never interrupted (Sumeet Kotian is the editor).

But the real merit of such storytelling lies in the complexity it addresses, while maintaining a lightness of touch. Farzi is not based in an utopian world where the middle-class triumphs, led by an unhinged artist. Instead, it unravels as a cautionary tale, presenting both what they can do and what can be done to them. Shahid Kapoor is phenomenal as the face of that crisis — the artist who (mis)believed his art to be his armour. The actor has always been as good as his director (it is not incidental that his finest performances have come from his collaboration with Vishal Bhardwaj). In Farzi, he inhabits his arc with unmatched precision. There is a deliberate opaqueness in his character and Kapoor portrays it without a false beat.

Then there is Kay Kay Menon, essaying the role of the man instrumental in causing financial terrorism in India. As Mansoor Dalal, the actor is so good, that he makes scenes better by just being in them. There is a particular moment where he realises that he bought a painting, at an obscenely high price, thinking the man in it is Van Gogh when in reality it is the painter’s brother. No amount of description can relay the comicality he evokes by saying nothing. By now, there is a legit Raj and DK universe and the actor just fits in it.

Much like The Family Man, Farzi is a politically charged show that tells more than it shows. The makers competently use long-form to delineate a nuanced portrait of a nation that remains vulnerable to foreign powers. But much like their successful 2019 venture and its sequel, the gaze remains steadfastly inwards.Through the concern of what others can do to India, they are articulating another pressing question: what is India, riddled with inequality, doing to its people?