Hero In Action, Or Action Hero? On Shah Rukh Khan's Post-Pathaan Rebranding

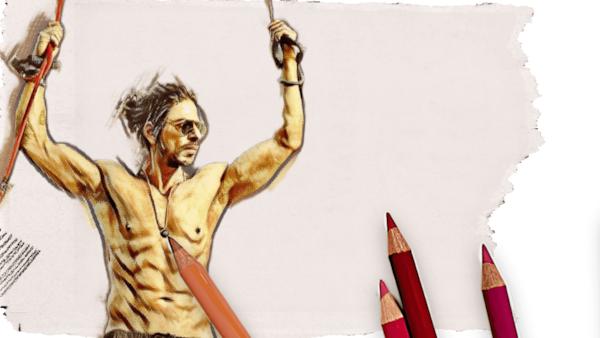

The superstar is being hailed as an action star after Pathaan. But this discourse overlooks an essential aspect of Shah Rukh Khan's previous filmography, argues Manik Sharma.

Last Updated: 02.56 PM, Jan 29, 2023

In a scene from Pathaan, an injured, wounded Shah Rukh Khan sits on the floor of a moving train. “Mard ko dard nahi hota,” he quips — then yelps meekly on being touched. It’s a scene that perfectly captures the actor’s capacity for self-deprecation. Many have already declared Pathaan as the rechristening of Hindi cinema’s greatest romantic star as an action hero, a shift seemingly necessitated by circumstance rather than sentiment. What this claim also underlines is how we have chosen to remember Khan as the romantic hero who was accepted, as opposed to the action star who was repeatedly rejected. Even at the height of his stardom, Khan never stopped dabbling in action, only to be reclaimed as the romantic. What has so obviously changed in the 20 years since, is the gaze of the audience — and the landscape of contemporary masculinity.

Khan’s first brush with the tropes of the action film hero probably began as early as Karan Arjun (1995). Koyla’s explosive climax was another hat-tip to the raw, jubilant physicality that Khan could bring to the modest action sets of that era. In the rather frivolous One Two Ka Four (2001), he played a police detective, as stylish as he is witty and garrulous. In Farah Khan’s Main Hoon Na, Khan fought an eerily similar villain to Pathaan’s, who had been wronged by his country and was en route to retaliate. In Don (2006), Khan of course essayed the popular anti-hero, executing action sequences that pushed textural boundaries with believable grandeur. A step up for that time. As for the world of espionage, there is probably no film better than Khan’s own Baadshah (1999), that highlights the direction our cinema has taken.

In Baadshah, a typically self-deprecatory Khan accidentally falls into a spy adventure. He mimes, dances, embodies the commoner, and leaps across the scene with the joviality of a man ready to gnaw at elitist ideas. Rather than patriotism, love is the mission. In Pathaan, a much older Khan shoulders a more uncomplicated role where he might jest every now and then, but remains serious still. Baadshah is never quite remembered the way Khan’s romantic films were, but it came at a time when we sought lovers more than we sought saviours. Our enemies haven’t necessarily multiplied in the years between both films but a sense of uncertainty, and anxiety about the future has possibly fuelled this need for a form of heroism that celebrates uncommon excesses.

Khan was always an excellent exponent of nimble-footed aggression. Despite having played the antagonist in films like Darr and Josh, his idea of action never originated in brute force. Even in Pathaan, he simply looks sharper and guileful compared to his opponents. At no point does he overwhelm anyone with raw strength. In fact, it’s something that both Aamir and Salman have never been able to produce — the very lightness of a ballet dancer gliding past the screen, effortlessly punching and jumping across the canvas. The irony here is that in his physical prime, Khan’s oeuvre of sentimentalism outclassed the infectious energy of his runs, sprints, jumps and kicks. His action hero avatar never quite materialised to the scale that his open-armed tenderness did. Twenty years later, he has taken to the role that he has already drawn in his own image. Only now, he has reluctantly applied to its old tape the needle of a new socio-political dawn.

Even in Pathaan’s exuberance, Khan remembers to bend, just enough, to not distance himself from his audience. There are allusions to his age, to the fragility of a certain brand of masculinity and even in the throes of a cross-court battle of ideologies, a moment to contemplate what patriotism really means. The sprightliness has obviously waned over the years, but a bulkier Khan has now resorted to guns, planes and bombs to extract a form of muscular joy that also, somewhat, contradicts the perkiness of his previous self.

That, however, is simply where cinema and its latest imagination of the action hero is headed. Here you manufacture the canvas that you wish to supplant your hero with. Back in the day, Khan built his own. In Karan Arjun, for example, he used a miserly catapult to overturn a police car. Today grenades, guns and helicopters populate the scenery of the average actioner with sobering indistinctiveness. The action hero, thus, doesn’t earn his stripes but merely fits into the glove of a hyper-masculine world. It’s much easier.

Khan’s latest foray into the action genre with Pathaan might be his most celebrated yet, but he did more for and with action, in his earlier days. But because he is who he is, even his second coming as an action hero has the same old heart, humour — and most crucially — humility.