Hollywood and the Indian subcontinent: How mainstream American films continue to exoticise, primitivise India

From yellow-grading frames to depicting India as the ostensible land of spiritual awakening, examining how Hollywood treats the Indian landscape in movies.

Last Updated: 09.21 AM, Oct 05, 2021

Chris Hemsworth’s Extraction (2020) rode high on the premise of being one of the first commercially viable action flicks to be predominantly shot in India. After the trailer release, Indian fans could not stop gushing over the Hollywood star parkouring in a setting they have an intimate connection with. Upon release though, many wondered why the specific part of the film shot in India was heavy in sepia tones while the sequences canned in the developed countries were true to colour, with clear blue skies and traffic-less open roads. The yellow filter is typically used in Hollywood films to depict dusty and tropical climates in countries like India, Bangladesh and Mexico. On the contrary, tropical regions like Florida and cityscapes like New York are swathed in cooler blues and greens, representing a progressive, almost futuristic landscape.

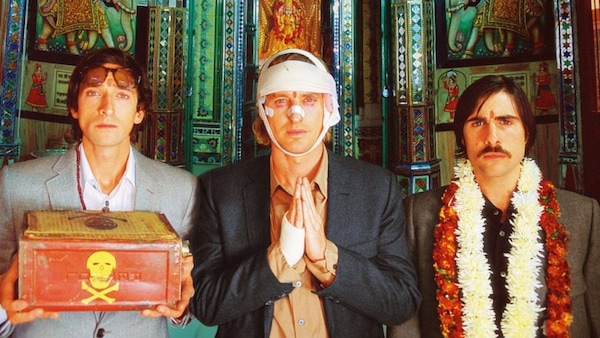

Extraction is by no means the first film that primitivised developing countries by playing with the colour palette. Steven Soderbergh’s 2000 film Traffic, about a Mexican drug trade, turned discernibly yellow during a desert scene. Twitterati has routinely pointed out how Breaking Bad would turn jaundiced every time a scene would be set in Mexico. Likewise, The Darjeeling Limited and Slumdog Millionaire (2008), both set in India and helmed by white directors, had an overall warmer colour palette.

In fact, Danny Boyle’s Academy Award-winning drama, based on a true rags-to-riches story, was heavily criticised for showcasing ‘poverty porn’ by only focusing on the depravity and poverty in the country.

White filmmakers have routinely come under scrutiny for exoticising anything West-adjacent on non-West. Not just because they drown out the voices of the marginalised, but also because films dictate and shape our understanding of cultures and ethnicities different from us. Films like The Jungle Book and Around the World in 80 Days have impacted how the West audience perceives India. After repeatedly being fed the same kind of information, audiences create in their mind a skewed blueprint as reference for the same culture.

These kinds of films appeal to Western audiences because they offer something unknown. “The Western spectators find such Eastern mystical stories to be exotic, unfamiliar and consider the movies as representing otherness,” says Indonesian scholar Ekky Imanjaya in her 2009 article The Other Side of Indonesia: New Order’s Indonesian Exploitation Cinema as Cult Films.

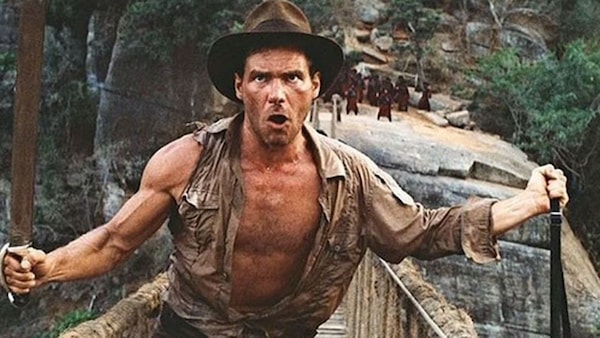

Take, for example, Indiana Jones: The Temple of Doom (1984). Film Critic Bharadwaj Rangan noted in an interview with BBC how films like Indiana Jones have perpetuated negative stereotypes of India being the land of elephants and snake charmers.

“Like Spielberg's Indiana Jones and Temple of Doom – supposed to be set in India, but actually shot in Sri Lanka – showing our savage culture with people eating snakes and monkey brains," he was quoted by the publication. Similarly, Eat Pray Love (2010) sees Julia Roberts undertake a journey of self-exploration, where India is her spirituality station. It is that part of the Orient that the West feels has answers to their religious reckoning.

In The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2011), India is a land of excesses and wish fulfilment. The British visitors are amused by the peculiarities that the country has on offer. Of course, the main roads have camels, elephants, horses, bullock carts and buses coexisting. Of course, the guests are shell-shocked when they are welcomed by a flight of pigeons. It’s a new world, Dame Judi Dench declares, one that has screaming children perpetually banging on windows, or buses waiting to bang into each other. For them, India is a country of “colours, light and smiles” and other such kitschy aggregates Coldplay sings about in their Hymn for the Weekend.

Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited (2006) used these very tropes of mystical India in a self-aware parody of undergoing a life-changing experience by discovering India, something the Beatles kickstarted back in the 1960s. It uses a train as its backdrop as it satirically investigates claims of spiritual emancipation through rosary beads, music and religions. They are in temples, ghats, deserts, inside homes with newborns, bathing in streams, engaging in every activity in the handbook to Indian stereotypes. It is possibly the closest a Hollywood film ever came to demystifying the idea of India, albeit through pastiche. But Anderson’s film ultimately slips into familiar territories by showing its three protagonists having spiritual enlightenment at a funeral.

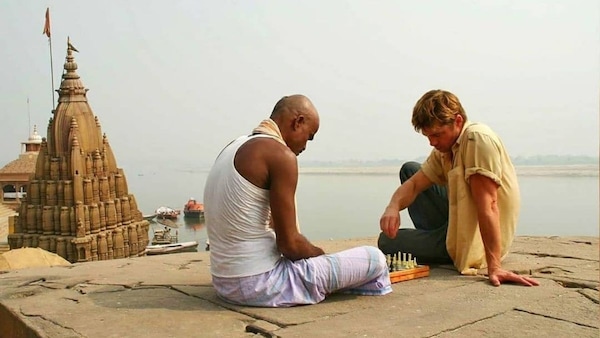

There are other films that have included India in a tokenist move, be it Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol or in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008). In the latter, as one would anticipate, Brad Pitt’s Benjamin Button visits Varanasi in an attempt to understand his age reversal condition through spirituality.

As Indians, our colonial hangover dictates us to lap up everything that even obliquely references India. But in the recent past, films like The White Tiger (2021) have displayed a keen interest in representing India without its exotic trappings. Is it enough to undo centuries of misrepresentation? Perhaps not. But it is a beginning towards change, inclusivity and sensitive filmmaking.