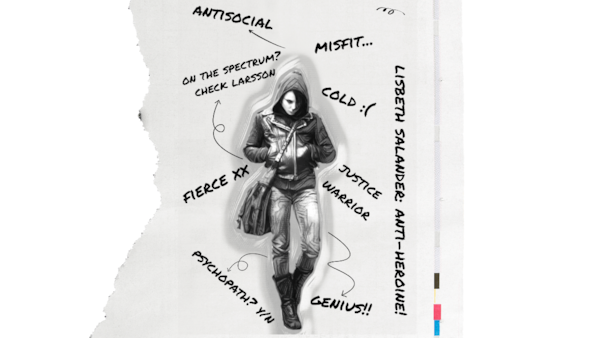

How A Girl With A Dragon Tattoo Became The Anti-Heroine To Rally Us

January 2023 marked 15 years since the English translation of Stieg Larsson's The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo first appeared in print. (The Swedish original was published in August 2005.) It brought Lisbeth Salander, an anti-heroine unlike any other, to a global audience. Sunil Bhandari delves into the psyche of one of contemporary fiction's most compelling characters.

Last Updated: 04.17 PM, Feb 12, 2023

WHO WOULD HAVE THOUGHT that a morbid, anti-social, rude young girl with a macabre sense of humour and deathly-pale pallor would become such a rage? Yes, I’m talking about Wednesday Addams, who heralds (in the Netflix series where Jenna Ortega reboots the pigtailed icon for a new generation) — yet again — the advent of the anti-heroine. Oh, not that there haven’t been more than a few: the femme fatales Catherine Tramell (Sharone Stone in Basic Instinct) and Bridget Gregory (Linda Fiorentino in The Last Seduction), the anarchist Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie in Suicide Squad, Birds of Prey), et al. All characters who have transcended their own stories and entered our collective folklore.

Even in this august company, there is one anti-heroine who has attained an almost mythological status that won’t be easily dislodged:

Lisbeth Salander.

Slight, self-centred, a social misfit — the heavily tattooed and pierced Salander is a character created by the Swedish writer Stieg Larsson, the protagonist of his books The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played With Fire, and The Girl Who Kicked The Hornets’ Nest, all published posthumously after his death in 2004. Salander appears in the Swedish films of the same names (in which she is played by Noomi Rapace) and in the English-language one based on the first (helmed by David Fincher, no less; starring Rooney Mara). For the purpose of this essay, I am not considering the dismal spin-offs — both in print (by authors David Lagercrantz and Karin Smirnoff) and on screen (with Claire Foy) — that have painted Salander as a one-dimensional action hero.

Within the complex plotting of Larsson’s books, Salander’s nature emerges — a conglomeration of traits that, individually could be cringeworthy, but together alchemised into something incredibly potent:

Lisbeth will not talk if she does not want to. She is possibly on the spectrum. She will not mouth niceties like “thank you”, no matter what/how-much-ever someone has done for her. She will not trade life stories. She will not ask for help. She will resolve her problems herself, regardless of the toll. A bisexual, she can be celibate for months, then seek sex ravenously. She is bereft of scruples when she delves into the very entrails of her targets’ private lives. For Lisbeth, nothing is sacrosanct.

RESEARCHERS Melissa Burkley and Dr Stephanie Mullins-Sweatt comprehensively analyse Salander in their book, The Psychology of the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,exploring the character’s motivations and traits. One of the key subliminal themes the book explores is Lisbeth’s self-identity, particularly in relation to societal expectations of women. The authors argue that Lisbeth's experiences of abuse and trauma in her formative years led her to reject societal norms, leading to her fierce independence and non-conformity. They also examine how Lisbeth's sense of identity is closely tied to her desire for control and power, as demonstrated through her hacking prowess and her ability to manipulate those around her.

Burkley and Mullins-Sweatt also deconstruct Lisbeth’s gradually evolving relationship with her co-protagonist, the journalist Mikael Blomkvist (portrayed onscreen by Michael Nyqvist, Daniel Craig and Sverrir Gudnason). Her interactions with Blomkvist represent a way for Lisbeth to process her past traumas and to start trusting people again.

Salander is often mislabelled a psychopath or even a sociopath, but she isn’t. She may be violent and hostile, and openly cock a snook at societal rules, but Lisbeth has her own version of a moral code, a uniquely calibrated internal compass for right and wrong. This drives her actions in often strange — and strangely ethical — ways. She has the incredible integrity of a person who sets (and follows) her own rules; is unwaveringly loyal and faithful to her allies; sharp and uncompromising when wreaking vengeance on those who have wronged her/others; and eminently resourceful.

Beyond these attributes though, what is the “x-factor” that makes Lisbeth Salander so fascinating?

I think Lisbeth has an intense gravitas, which I have seen in people who carry themselves with a sense of themselves: she is comfortable being herself. She attracts because she does not try to. You might be drawn to her or repelled by her — but you can’t ever ignore her. It’s almost a privilege to be on Salander’s side — even if she won’t even acknowledge your support.

THE CLOSEST HEROINE I can think of, cast in the same compelling mould as Lisbeth Salander, is Modesty Blaise (more in the books than in the mediocre, spoof-like films based on her adventures). Both are strong women, ready for action, deeply committed to those they care about. Even though Modesty is a sophisticate and Lisbeth callow, they share a commonality in terms of their core. And that is what makes others try so hard to be acknowledged by them: either to be considered their friends, or to foist their “superiority” on them.

Lisbeth’s frail strength is beguiling — and a challenge to [toxic] masculinity, resulting in numerous incidents of attempted subjugation and violence. It is interesting that the characters who surround Lisbeth — Blomkvist and Dragan Armansky, Erika Berger and Holger Palmgren — all display resolve, fortitude, and have agendas of their own. They each stand by and alongside Lisbeth on their own terms. Even Lisbeth’s foes — Alexander Zalachenko (Salander’s father) and Dr Peter Teleborian (the villainous psychiatrist) — are formidable and resourceful. This avoids the easy device of having weak characters who will further underscore Lisbeth’s iron will.

Of course, It is a wish-fulfillment of fiction that Lisbeth Salander and Modesty Blaise always triumph. But irrespective of the physical thumping they deliver to their enemies time and again, they are anyway victors — by dint of being themselves. And in that sense, Salander transcends the stories she is a heroine of, as she herself is as compelling as her tales.

In her book, The Psychology of Love, Elaine Hatfield emphasises the role of similarity and complementarity in attraction, and has suggested that people are often attracted to people who share their values, interests, and personality traits, but equally — if not more — to those who complement their own strengths and weaknesses.

Of course, Lisbeth is a difficult character to get enamoured with, because she is mean, unscrupulous, and unremittingly self-centred. It is the beauty of her characterisation and the manner in which both Larsson and the films (up to Fincher’s) have etched her, that makes you feel a sense of gloom at the end, that there will be no more Lisbeth Salander except in the stories that have already been written. Because she is the kind of person you never want to let go of, no matter how difficult the relationship with her might be. Among iconic anti-heroines, Lisbeth Salander is the one who haunts the heart and mind the most.