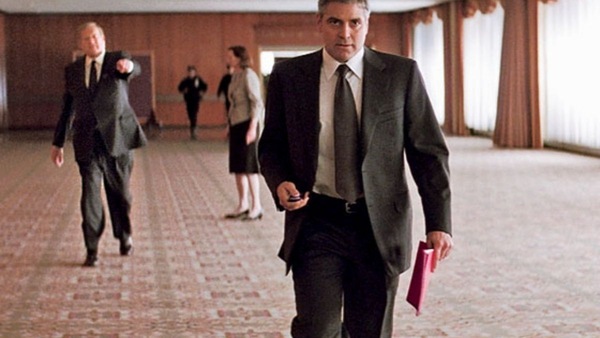

Michael Clayton, George Clooney, Tilda Swinton’s legal drama, was a patient exploration of professional dilemmas

As George Clooney and Tilda Swinton’s Michael Clayton completes 14 years of release, taking a look at how Tony Gilroy’s directorial debut was a departure from high-octane courtroom dramas of the previous decades.

Last Updated: 08.56 PM, Oct 05, 2021

Michael Clayton did not spin gold at the box office when it debuted in theatres in 2007. Although, it turned out to be a critic and awards favourite, with Swinton claiming the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. Director Tony Gilroy’s legal film was preceded by a long list of films like 12 Angry Men (1957), To Kill A Mockingbird (1962), The Verdict (1982), My Cousin Vinny (1992), A Few Good Men (1992), Erin Brokovich (2000) and Chicago (2002), that were characteristically impassioned, high-octane and somewhat sassy. As a matter of fact, legal dramas and police procedurals even today are identified by adrenaline-fuelled narratives, be it Suits or The Good Wife. They are also redemptive in most cases.

Michael Clayton had none of it. The film was marked by its remarkably subdued and slow-burning narrative, about the titular lawyer’s endeavour to fix his firm’s latest mess — to rein in a colleague’s mental breakdown which he had while defending a corrupt agrochemical conglomerate. The movie made no qualms about exposing the ethical corruption in corporate setups, exploitative hierarchies, personal distrust and the ambiguity of law itself. It is sceptical of money-minting corporations, but never didactic. Gilroy conjured up a realistic world that isn’t concerned with fiery courtroom exchanges. It is a behind-the-scenes expose of a system that routinely fails those it feeds off of.

The tone is set from the opening voiceover of a disenchanted attorney — Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson) — who declares that he is an “asshole of an organism whose sole function is to excrete the poison, the amyl, the defoliant necessary for other larger more powerful organisms to destroy the miracle of humanity.” He says he’s been “coated in this patina of shit for the best part of my life” and will possibly take this burden of guilt to his grave.

Enter Clayton, essayed by George Clooney, is a suave lawyer who has been summoned to clean up after Arthur has a meltdown for spending over a decade of his life “defending the weed killer,” the billion-dollar agrochemical giant U/North after discovering that the company is guilty of poisoning many of its customers.

Unlike Arthur, Clayton hasn’t really had a moral reckoning. He is world-weary, is separated from his wife and son, and battles a gambling addiction. He is also desperate to pay off the loan sharks he is indebted to after his brother Timmy loses the money to feed his drug addiction.

Cinematographer Robert Elswit, who had also collaborated with Clooney on Syriana and Good Night, and Good Luck, crafts a visually bleak world that mirrors the thematic darkness of the film. Almost all scenes are either set at night or in spaces with artificial lights — be it the long corridors of the law firm, the hotel rooms, the empty streets or the police station. The scenes in natural light are far and few, and mostly involve Clayton’s son Henry, who is the only unsullied soul in the Michael Clayton universe. It is also riddled with voiceovers and flashbacks, breaking the unilateral flow of the narrative. It flits from one subplot to another, offering no respite to the casual viewer. The world is relentless, yet Michael Clayton demands the audience’s complete attention, lest they miss out on key developments.

Henry’s favourite book Realm and Conquest (a fictional book that becomes a metaphor for moral corruption), is introduced fairly early in the movie. The science fiction novel, Henry describes to his father, is set in a small a no-man’s land where there are many characters but no one trusts the other. This world has no allegiances or friendship, just a solitary fight for the survival of the fittest.

This overbearing sense of isolation and claustrophobia is suffered not just by Arthur, but also by U/North boss Karen (Tilda Swinton). She is always seen inside enclosed spaces, inside her office, in her small bedroom, or a bathroom. On the other hand, the world outside is vicious too. Hence, Clayton, torn between his sense of duty towards his firm and his own conscience, is also driven to isolation. He never has roots to belong, or a safe haven he can escape into. Clayton moves in and out of spaces, the prison cell, his office, his home or his firm, but none of them has specific identities or discernable features; it is an amorphous, transient world.

Even in the end, the film does not take a triumphant leap while taking down the ostensible villain in the story. Here, Clayton summons a cab and rides off to yet another space where he doesn’t quite belong. It does not conclude on a happy note, since Clayton is still knee-deep in debt and is at the mercy of his bosses to wriggle him out of the situation. Neither is Swinton’s Karen an eye-rolling antagonist. She is motivated not by evil intentions, but by the desire to protect an institution she serves.

Michael Clayton is neither emphatic nor dismissive. The protagonist is not a hero who delivers pedantic lectures on absolute rights and wrongs. It’s a silent contemplation about the world we belong in, where the truth is manufactured, maimed and adjusted to suit the teller’s tale.