Netflix’s ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ stirs discourse on censorship trials

Based on DH Lawrence’s scandalous last novel, the Netflix film - starring Emma Corrin and Jack O’Connell - once again sheds light on why the book was banned globally for decades

Emma Corrin and Jack O’Connell in the Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre directorial

Last Updated: 10.55 PM, Jan 06, 2023

“Looking back, it’s quite laughable that this book was ever banned, because I think it’s far from being offensive. Rather, it’s a fascinating tale,” remarked actor Jack O’Connell in an interview about DH Lawrence’s last - and arguably his most notorious - novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the story of which has inspired many film scripts over the years. Currently featured among the ‘Top Searches’ on Netflix, Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre’s latest cinematic adaptation has once again stirred discourse on why this scandalous literary piece had to be censored for decades.

The plot of the Netflix film revolves around a young aristocratic woman Constance (Connie) Reid - played by Emma Corrin (remember Princess Diana on The Crown Season 4) - who gets married to an upper-class baronet, Sir Clifford Chatterley - played by Matthew Duckett - and is now addressed as Lady Chatterley. Unfortunately, Clifford suffers an injury during World War I and has since been paralysed from the waist down. The couple then relocate to their sprawling Wragby estate, situated near a mining village. Lonely and worn out, Connie secretly starts an affair with the property’s gamekeeper, Oliver Mellors (Jack). Their forbidden love soon grows into a passionate and emotional bond between two people deprived of compassion and human connection.

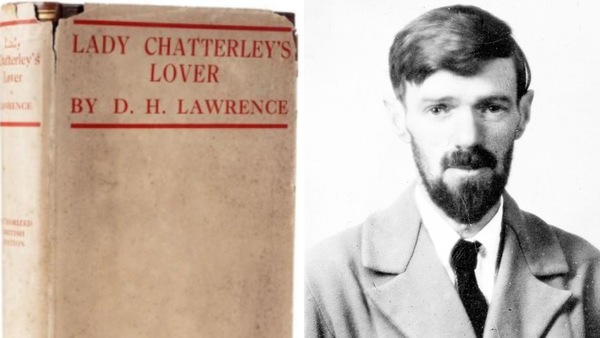

Much like Lawrence’s previous works - titled Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow and Women in Love - Lady Chatterley’s Lover too had to go through several censorship trials. In fact, the transgressive novel was considered problematic from the word go. It was privately published first in 1928 in Italy, followed by another edition in France a year later. Obscenity, perhaps, was a gentle way to describe why it was banned. Many found it outrageous because of its depiction of infidelity (a relationship involving an upper-class woman and a working-class man), explicit sexual content and rampant use of the four-letter words. The fact that Connie and Oliver represented two drastically different social statuses failed to serve as an acceptable plot for a pleasant read. More than the profanity though, people raised their eyebrows at the author’s unapologetic portrayal of a young woman owning her body and prioritising sexual pleasure over devotion toward her paralysed husband.

The hard-nosed lawyers, politicians and literary thinkers of England at that time found the narrative insufferable and way out of line. According to them, it contained explosive material that could potentially pollute the minds of women and the working class, thanks to Penguin selling the book at an affordable price. This, among other factors, eventually led to its prosecution under the Obscene Publications Act. Securing permission to commercially publish the uncensored version became a matter of great concern. It was only after Lawrence’s death (in March, 1930) that heavily censored editions of the novel were published in the UK and the US.

Nearly three decades later, Barney Rosset - the publisher of Grove Press in New York - sued the US Post Office in 1959 for trying to expropriate his unexpurgated edition of the literary piece. Thankfully, Appeals Judge Frederick van Pelt Bryan observed that “Lady Chatterley’s Lover had significant literary merit and to exclude the novel from being mailed on the grounds of obscenity would fashion a rule which could be applied to a substantial portion of the classics of our literature, and that such a rule would be inimical to a free society”.

The book was also banned in Canada, Australia and Japan. A 1964 Supreme Court ruling had blocked it in India too. In the Ranjit D Udeshi Vs State of Maharashtra case, the partners of a company that owned a bookstore were prosecuted under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) for selling copies of the allegedly obscene book. However, Ranjit argued that Section 292 of the IPC is violative of the rights to freedom of speech and expression under the Indian Constitution and that as a whole, the book cannot be considered. The Apex Court relied on the famous ‘Hicklin Test’ to draw the line between art and obscenity.

Writing this novel, among others, may have earned the author the reputation of a ‘pornographer and wasted talent’, but a closer look at the themes that he touched upon in Lady Chatterley’s Lover would indicate that those are relevant even today. Although the explicit sexual descriptions made headlines, the intention of the narrative was to primarily focus on an individual’s need for integrity and wholeness, and how the key to this integrity is cohesion between the mind and body, academic Herbert Richard Hoggart observed. Lawrence may be a little ahead of his time (or rather too bold), but he wasn’t distasteful. In fact, the manner in which he intricately describes every emotion, desire and touch in the book, it only speaks volumes about the literary genius that he was.

Cut to director Clermont-Tonnerre’s thoughtful adaptation, the film makes the sex scenes look no less than a piece of art. It all began when the French filmmaker was re-reading the book in April 2020 amid a lockdown. “We were all isolated and yearning for human connection in the middle of a pandemic. That for me served as the most urgent need to talk about human touch in nature. Of course, this novel is also one of the firsts to discuss openly about human sexual pleasure. It’s an important reminder that contrary to being shameful and dirty, sexuality is pure and beautiful, and so it was glorified by Lawrence. The book tried to address the concerns over obscenity when it comes to a woman’s sexuality or her taking ownership of her own body. Decades later, we are still facing the same challenges, and it’s extremely important and timely to shed light on that,” she said during an interview. The film delicately handles the curiosity and desire for sexual pleasure, in tandem with the book’s warmth and thrill, making the scenes look more artsy than erotica.

Emma, on the other hand, feels that it’s rare to find a female character showing the courage and willingness to look for what she wants and fight for it. In an interview, the actor said, “Connie was ahead of her time, and in her journey of self-discovery she becomes aware of what she wants. But apart from the strength to seek it out, she also displays a sense of curiosity and playfulness. The intimacy and joyfulness amid the elements of tragedy is what makes the text so rich and endearing.”

This, however, isn’t the first time that the classic risqué novel was adapted for the screen. In 1955, French filmmaker Marc Allégret released the first adaptation, starring Danielle Darrieux, Leo Genn and Erno Crisa. Another French director Just Jaeckin’s film hit the theatres in 1981. This movie featured actors Sylvia Kristel, Shane Briant and Nicholas Clay. Interestingly, there have been other movies based on books that were banned for ‘explicit sexual content or sexual references’. Among the most popular ones on the list are Gone With the Wind (1939), Lolita (1962), Slaughterhouse Five (1972), Sophie’s Choice (1982), The Color Purple (1985) and The Great Gatsby (2013).