Newsletter: In The Intern, Fodder For A Father Figure

This is #ViewingRoom, a column by Rahul Desai, on the intersections of pop culture and life. Here: The Intern.

Last Updated: 02.19 AM, Jan 19, 2023

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on January 5, 2023. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, my father was the coolest parent in the neighbourhood. He threw wild parties. He had expat friends. He loved The Beatles. He swore by Wodehouse. He gladly fed my obsession with beer heads; I’d feast on the foam of every glass in the room before falling asleep next to him. He was the only one who smoked in public: unabashedly, stylishly. He was the only one who owned a Volkswagen Beetle (which went up in flames, but that’s a story for another day).

His ‘love marriage’ with my mother was the stuff of legend. He was the only top-tier MBA graduate in a town of businessmen. Other families celebrated Diwali; we celebrated Christmas. He would come home early from work to play cricket with me. He’d agree to umpire at our colony matches. He would take me to the cinema hall in the middle of my exams. Other kids came over to hear stories about his work trips to New York and London. He was nothing like their parents. In fact, he was nothing like the orthodox, old-school fathers we saw in the movies.

And then I grew up. Slowly but steadily, those rose-tinted glasses came off. The biggest tragedy of adulthood is that we start seeing our parents as real people. As flawed, fragile, fallible humans. The spell — shaped by caretaking, control and nurturing — dissipates. It becomes disorienting to view them through the lens of things like morality and mortality. And it becomes difficult to unlearn who they are. Now I resent the fact that my father is nothing like the orthodox, old-school men we see in the movies.

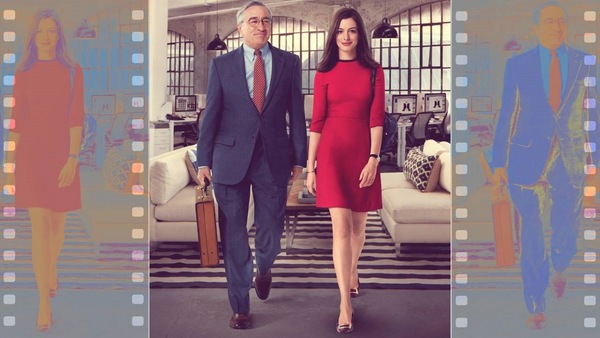

One film, in particular, deepens this feeling. The Intern is to ageing what Before Sunrise was to love. Just as Richard Linklater’s romance made an entire generation feel terrible for not having the perfect meet-cute, Nancy Meyers’ feel-good comedy makes us feel bad for not having the perfect old dad. The image of Robert De Niro playing a spirited 70-year-old widower who works as a ‘senior intern’ is unnerving. As a man in his twilight years, he’s so aspirational that it hurts. It’s like an Anthony Hopkins Instagram reel on loop.

EACH TIME I REWATCH The Intern, De Niro’s character, Ben Whittaker, reminds me of everything my 69-year-old father is not. I can’t help but envy the man. Ben is modest and open-minded. His worldview is flexible. After losing his long-time wife and travelling the world, the retired executive — who worked in a phone-book company for 40 years — applies to an e-commerce fashion startup. What starts out as a sweet attempt to stay occupied morphs into a late-life learning experience. Ben is receptive, and has no airs about his own exemplary career; he is happy to do basic intern stuff and absorb the energy of the new-age workspace. He is curious but polite, infusing the office with a touch of vintage chivalry. Over the course of the film, he becomes a friend and father figure to the overwhelmed young founder, Jules (Anne Hathaway). He is not clingy, needy, nostalgic or arrogant; even his “in our days” moments are self-deprecating. Ben’s humility reveals him as a rare old-timer who lives in the moment — and practices what he preaches.

My father, in stark contrast, lives in the past. He reminisces about the parent and partner he once was. He tells stories about all the high-profile jobs he had, without mentioning that he lost most of them because of his alcoholism. He is no widower, but my parents have been separated for a decade and he refuses to acknowledge it. He puts up old photos on his social media accounts in a manner that suggests we still live together like a happy family. He hates travelling, confidently forming opinions on foreign countries based on what he’s read or heard about them. He never asks questions; he only speaks in the tone of answers, even when he doesn’t have any. He is anything but open-minded. He spends most of his days cooped up in our old apartment, tweaking his CV and applying for CEO positions at fancy multinationals. He has rejected multiple offers of teaching and guest lecturing at colleges, determined instead to extend his stilted corporate career. His knowledge is evidently too precious to be shared.

He snaps at anyone who suggests retirement, unable to come to terms with the fact that he’s squandered all that early potential. He has stopped being a mentor to young students and employees. He even lies about the city he lives in; he waxes eloquent about Mumbai evenings on Facebook while staying in Ahmedabad, almost as if he’s willing people to mistake his memories for his truth. In short, my father has monopolised that bridge between pride and delusion. He has been pretending — and anticipating — for so long that he has lost track of reality. I used to believe that he was too intelligent to be happy in this world. Other fathers, most of whom didn’t have half his mind, led blissfully successful and oblivious lives. They were happier because they were too thick to understand the nuances of sadness. But now I’m beginning to think he’s too tragic to be intelligent anymore.

I know it’s unfair to compare my father — a complicated but actual individual — to fictional characters like Ben Whittaker. The Intern is essentially a fantasy film. It’s an elegant ‘buddy’ comedy in which the older generation teaches the messy younger generation a thing or two about life. But even when I get moved by stories about grief and caregiving now, I struggle to see my father in any of the hapless protagonists. If anything, I see him in the side characters, the sort who’re stubborn and dismissive and unwilling to evolve. That’s why Hopkins’ performance in The Father keeps haunting me; the man’s struggle is rooted in his indignity and ego, his sheer inability to respect the withering of his mind. You can tell that he’s an arrogant parent being humbled by the sands of time.

It’s not just the movies, though. I spent some time with a friend and his parents last year, and all I could do was wish that my parents were as self-effacing, kind and selfless as them. I loved observing them, their little gestures of affection and their genuine zest for a life that was conspiring to break them. I found myself smiling there, in their hometown, the way an orphan might at a Christmas foster-family dinner. It was somehow fulfilling and sad at once. That week made it harder for me to accept my father for who he is. The ghost of Ben was everywhere.

The upside is that, through my father, I am learning how not to age. I am learning to be open, vulnerable, honest and humble. I am learning to unlearn. Perhaps the only thing we have in common today is our shared fondness for one Hindi film. I remember when Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa released back in the early 1990s, my father was possibly the only person in Ahmedabad who declared it an instant masterpiece. He took me, an 8-year-old kid, to watch it during my exams. At first, I didn’t get the fuss: Where was the love story? Where were the fight sequences? Where was the hero? Where was the Happily Ever After? But I enjoyed watching my father crack up at the scenes of Goga Kapoor’s Don Anthony, marvel at the lanes of old Goa, and chuckle at Naseeruddin Shah’s playful performance as a priest in a land of warm peasants.

Most of all, he encouraged me to like Sunil, the shaggy-haired protagonist played by Shah Rukh Khan. Year after year, he let me develop a kinship with the story of a flawed, sensitive kid fumbling his way towards an identity. A boy desperate to win in romance, friendship, masculinity and family. A son yearning to be good enough to blow his (own) trumpet. A father learning to accept him for who he is — his talent as an artist, his disdain for academics, his quivering teen heart. And a parent who never stops seeing his child as a person.

Every time I watch the film, I call my father without really meaning to. He then proceeds to ask me questions about my life. Questions a senior intern would ask a young CEO that he admires. Questions that convey unconditional faith in the man I’ve become while I’ve been busy judging him for the man he is. Questions whose answers he does not pretend to know. I was never the coolest kid in the neighbourhood. But I grew up. And my father continued to watch me through those rose-tinted glasses.