Revisiting Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: Exploring the complexity of the landmark psychological thriller on its 61st anniversary

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is arguably one of the greatest movies ever conceptualised and executed by a filmmaker. As the thriller completes 61 years of release today, here’s a deep dive into the appalling world created by the master auteur.

Last Updated: 10.16 PM, Sep 08, 2021

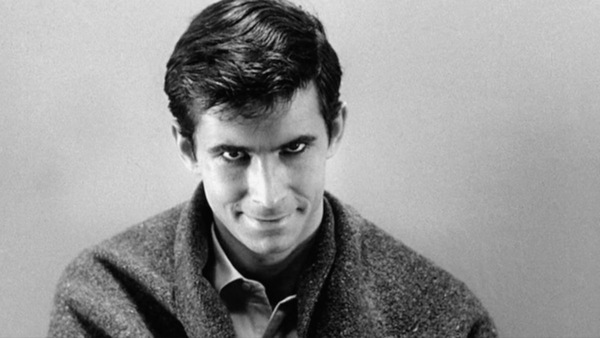

A stormy night, a shady motel, a grizzly murder inside a shower — Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 Psycho classic is shockingly macabre, that has viewers diving for the nearest blanket to hide in. The film follows a woman, Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), on the run who halts at a ramshackle motel on her way. The young owner Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) with a complicated relationship with his mother welcomes his new guest with a promise of restful slumber.

Critics through generations have endorsed repeat viewing of the movie in order to fully comprehend the terror bait Hitchcock sets for his audience. Indeed, Psycho is a deeply disturbing film that lends the point of view of a murderer — the intoxicating allure of domination, of repressed sexuality and the thrill of violence. Despite resistance from critics at the time the film hit the theatres, later scholarship has proven how Hitchcock was able to harness the depths of human desire in our unconscious and subconscious minds.

Not just thematically with the unconscious mind, the duology is reflected with the use of light and shadow in true Hitchcockian fashion. Light here is not illuminating, it is blindingly bright — from headlights of cars barely illuminating the menacing road to the pristine white bathroom splattered with blood, the light becomes increasingly discomfiting, almost an extension of the darkness itself.

The film was constructed in a way to unsettle the human mind. Reports state that the director intended to make the perspective the “closest approximation of the human vision” and thus wanted his cinematographer John Russell to shoot the film using 50 mm lenses. Hence, the viewers are not just spectators looking over a screen, they become as much a part of the action.

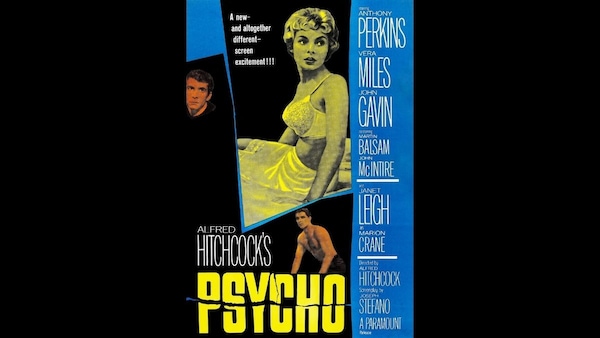

As a matter of fact, Hitchcock establishes the theme of voyeurism in the opening few shots — we see the characters of Sam and Marion through the curtains of their hotel room. The voyeuristic lens is used throughout the movie in key scenes, like when Norman is seen spying on Marion while she changes her clothes inside her Bates Motel room. But Psycho isn’t just titillation for the senses. Rather, it serves as a cautionary tale of how a society that valorises repressed sexuality is perhaps doomed to descend into madness. However, the clues to Norman Bates’ state of mind are embedded in the official poster of the movie, where Marion is placed gobsmack in the middle of the picture, with Sam and Norman or either corners. This triangulated formation is indicative of Norman’s attraction towards his mother and the sexual jealousy towards his father/ mother’s paramour.

The Oedipus Complex is explored through the relationship between Norman and his dead mother. His other personality is that of his mother that he quashes during the day and finds expression in the dead of night. In order to own his mother, he has internalised his mother’s personality, almost as an act of devouring. That he murders the woman he is attracted to was perhaps his mother’s sexual envy taking over, eliminating the possibility of a contender. His keen interest in taxidermy indicates that he has the know-how of preserving the bodies of those he loves. But this attraction towards his mother is also an extension of his confused sexual identity. He resents women with agency and feels emasculated around them. When detective Arbogast inquires about the missing Marion, he indignantly responds that he’s incapable of being tricked, let alone by a woman. In the concluding minutes of the film, a psychiatrist reveals Norman and his mother, years, “lived as if there was no one else in the world.” It is the fear of losing the child to another woman that propels Norman’s other personality to kill women he desires. We also learn that Norman lost his father at a young age, thereby never having to compete with another male figure for his mother’s undivided attention. Thus, when his mother chooses a new lover for herself, Norman realises his Oedipal fantasy and murders them both.

The graphic violence, as disconcerting as it was, paved the way for future neo-noir thrillers like Taxi Driver and Bonnie and Clyde. Critic David Thompson wrote in his essay, “The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock Taught America to Love Murder,” that with “the subversive secret out,” “censorship crumpled like an old lady's parasol.” He also argued that the violence humanises the deranged anti-hero. The infamous 45-second shower scene created history for its abject submission to madness. Bret Easton Ellis, the writer of American Psycho, declared that no other scene in the history of American filmmaking had dared to showcase something as “intimate,” “designed” or remorseless.

But this frenetic scene was stylised in a way that everything was implied, nothing explicitly shown. The entire sequence was filmed with extreme close-up shots, a swirling camera and rapid cuts. The background score, of screeching violins, amped the searing discomfort. The scene paved the way for future slasher films.

The film’s cultural impact has been written and debated about at length by scholars of psychoanalysis — whether the film legitimised violence against women in cinema. But Psycho was anarchic, it was non conforming, and a product of a rebellion against the stringent rules of censorship in the US at the time. However, what remains true to this day is that it shattered expectations, and it dared to tell a story previously unheard of.