Shehzada Is Kartik Aaryan Fan Service That Serves No One

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative about new Hindi films and shows. Today: Rohit Dhawan's Shehzada.

Last Updated: 05.22 PM, Feb 17, 2023

IN 1990, David Dhawan had made a film called Swarg. Starring Rajesh Khanna, Govinda and Juhi Chawla, it is a sentimental story about a domestic help (Govinda) avenging the wrong done to his employer. Given Hindi cinema’s perennial blindspot of recognising help in the language of servitude, Swarg reiterated a familiar tale of obedience. Three decades later, Rohit Dhawan, the filmmaker’s elder son, seeks to revamp the story.

On paper, it is not his father’s story although there are plenty of references (the bungalow in the film is referred to as “swarg”) to it. Shehzada is the remake of Trivikram Srinivas’s 2020 commercially successful outing, Ala Vaikunthapurramuloo. It is the same story (the producers of the original film have bankrolled this Hindi venture along with T-series). But if the Telugu venture gained from the enigmatic presence of its lead Allu Arjun, Dhawan’s film renders its protagonist Kartik Aaryan’s surging popularity as an impossible puzzle. There are reasons for it: Shehzada is not just insipid but so outrightly random that I am struggling to translate my feelings into words. It is not a good thing.

The tale is as old as time: two babies are swapped at the hospital and so are their fates. The reason for this is a bitter, middle-class man who wants to get even with his rich friend. Valmiki (Paresh Rawal) and Randeep Nanda (Ronit Roy) had both started out together. But then the latter’s luck shone and he got married to the daughter of a famous industrialist (Sachin Khedekar), thus inheriting a fortune. The film opens on the night both their wives give birth to sons in the same hospital. After the delivery, Randeep’s son stops crying. The nurse tending to the newborn fears he is dead. Valmiki chances upon this information and offers (without consulting his wife who gave birth to a human being, of course) to switch the kids. She agrees but just after the act is done, the baby starts crying, as if aware of his new impoverished status. The nurse now wants to restore both kids to their rightful parents, but Valmiki refuses.

His previous compliance is revealed as sinister design: he wants his own son to grow up in wealth, and ill-treat his friend’s child. There are two lessons here: Valmiki is the worst friend anyone can have, and the nurse is disgracefully bad at her job. (As if aware of her mediocrity, she slips and falls from the hospital’s corridor and lapses into a coma.) There is also a third lesson: stay close to your child after their birth.

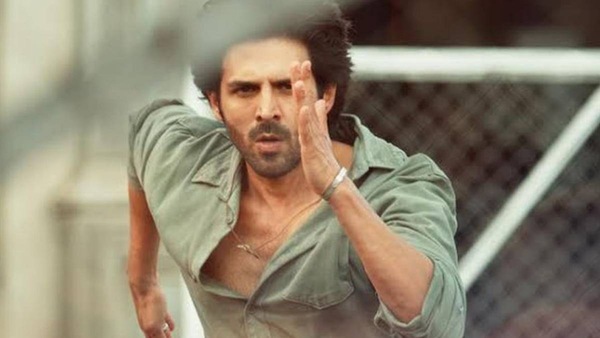

From here the film unfolds like clockwork: inane dialogues followed by Aaryan running in slo-mo to hit people. More inane dialogues (the actor tells a couple who can’t conceive “bacche pyaar ki tarha hote hain — karni nahi chahiye, ho jaani chahiye”) and more slo-mo action sequences. In between come songs, one too many. In fact, at some point every dialogue exists to preempt either a fighting scene or some song shot in exotic locations.

Without a doubt, Shehzada is designed with the express purpose of fanning the star-status of its male lead (he is credited as one of the producers). Aaryan does everything here: saves his family, punches people into thin air, flashes his trademark goofy smile on seeing Kriti Sanon (the actor has so little to do that she reminded me of the many girls who surround rapper Badshah in his videos; she occupies screen space, looks pretty but does nothing). He even delivers a monologue on…wait for it...nepotism.

Aaryan is not the most competent performer. With Shehzada, the sole thing going for him also falls flat: his charm. The screenplay (adapted by Dhawan) is so scattered that it would have been amusing if it was not so frustrating. Take for instance how the aforementioned nurse springs back to life to tell Bantu (Aaryan) the truth. To arrive at the moment, she is shown to be just lying outside her hospital room. The scene concludes with her dying but not before her bed, with her on it, circulates the entirety of the clinic. So keen is Dhawan on establishing the heroism of his protagonist that the rest of the characters are depicted as caricatures. The dreaded villain here (Sunny Hinduja), who is supposed to smuggle drugs, has an umbrella as his choice of weapon. Sachin Khedekar’s character exists to chill with Aaryan. But the worst brunt is faced by Manisha Koirala. Her character has at most five lines and three of them are reserved to praise Aaryan’s character and insult Raj (Ankur Rathee), who she believes to be her own son. The only person having fun here is Kunal Vijaykar, who essays the role of a Victorian-era inspired butler called Cadbury.

Dhawan is so interested in relaying the original story without telling it that the proof is hard to miss. Shehzada is set in Delhi but the setting plays zero role in the narrative. His nonchalance is further reflected in other instances. New characters keep popping up right till the second half without any explanation or purpose. And those he had introduced before (like Sanon and even Bantu’s sister) vanish like they ever existed. At some point, we see Aaryan riding a scooter. There is nothing wrong in that except the same vehicle was demolished by a truck a few scenes ago.

The only interesting bit in the boring procedure is the initial wickedness of Valmiki, and his refusal to be subservient to the people who employ him. That his character is named after the poet who wrote Ramayana, the Sanskrit epic monolith, hints at the fact that maybe someone like him — a middle-class clerk — who is routinely sidelined in Hindi films, will have the agency to write his own story. But even assuming this is giving Shehzada more credit that it deserves. The portrayal by Rawal is so farcical and the writing is so bad that at most, the film unfolds as poverty propaganda. Unsurprisingly, the Jindal family begins appreciating Bantu after the latter proves his loyalty. In that sense, Rohit Dhawan is not just saying the same thing as his father, he is doing it far more poorly. If this was his idea of an homage, it was not the brightest one.