The Song of Scorpions Is A Potent Reminder Of Irfan Khan's Genius

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative over new Hindi films and shows. Today: Anup Singh's The Song Of Scorpions.

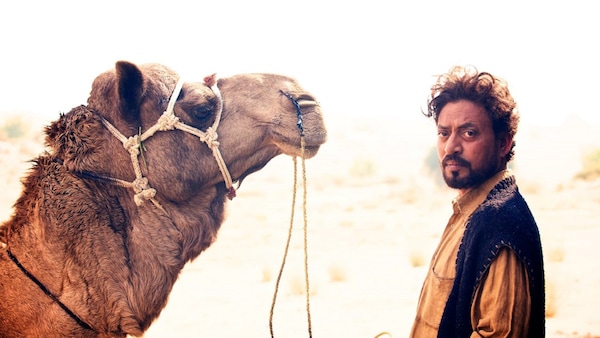

Irrfan Khan on the sets of The Song Of Scorpions, in January 2016. Image via Facebook/@thesongofscorpionsfilm

Last Updated: 02.13 PM, Apr 29, 2023

IN Anup Singh’s Qissa (2013), his stunning sophomore outing, a man is gripped with an obsession to have a son. The fixation is so blinding that it takes over his sense of morality, sensibility and more crucially, reality. After three daughters, when he has a child, he is ecstatic. The man declares a son is born as his wife looks on with pitiful rage. His male obstinance wreaks havoc, robbing a young girl of a sense of selfhood. She grows up as a man to retain her father’s palace of illusions.

Qissa is a blistering take on patriarchy with each frame bearing testimony to what happens when a man is confronted with a rejection by God: he decides to be God himself, thwarting the lives of others. By all accounts, the central character is despicable. But Singh mined this despicability to showcase the lonely undersides of it. The solitariness, traditionally used as atonement, only traps the character in a fate of his own making.

This distinct treatment of gender is reiterated in his third film, The Song of Scorpions. Much like Qissa, Singh designs it as a folktale. The setting is the unending sand dunes of Rajasthan and the pace is hypnotically sluggish. Science here has not dented the hold of superstition. A young girl, Nooran (Golshifteh Farahani), has the gift of curing the sting of scorpions. When she sings, the poison ceases to spread and people stop to look with an admixture of admiration and awe. Among them is Aadam (Irrfan), the camel trader who has been smitten by her for years. A widower, he tries shamelessly wooing Nooran, much to the dismay of the locals. Nooran, however, snubs him. She is more absorbed in becoming a healer, much like her grandmother Zubeidaa (Waheeda Rehman).

Time passes and life goes on. The languid frames set by Pietro Zuercher and Carlotta Holy-Steinemann lull us into the mythicality of the place. Singh keeps the momentum low but the urban soundscape in the distance enfolds a premonition. The pace will be disrupted. And it does. On a fateful night, Nooran is assaulted. The incident transfigures her life, relegating her to a social outcast. Women in the village want her to leave and men get a freeland to tease. In the midst, she comes back to an empty house. Her grandmother is nowhere to be found. During this time of upheaval, Aadam steps in and repeats his offer of marriage. He seeks healing the healer and she succumbs.

The timeless setting makes sense now. It was making space for a love story. There is no reason to doubt. What else is love for an Indian woman if not obligation preserving? The signs are all there. Aadam’s daughter, initially reluctant, warms up to her. Nooran learns to live a little. But Singh, as his previous outing evidenced, is not eager to affirm gender stereotypes. Neither is he interested in an undemanding story. Thus, the narrative reveals another knot, one that lends itself to a conventional gender strife.

What happens next is the strangest part of the film and also the most intriguing. Singh raises the stakes for a revenge tale and then later, slowly and all of a sudden, subverts it. Much like in Qissa where he had located inherent cruelty in a love that demands the sacrifice of selfhood, Singh uncovers brutality in an arrangement that resulted from something similar. I found it fascinating because it was symptomatic of the unique way the filmmaker views gender roles in general and men in particular.

In his last two films, men are depicted as tragic beings. They are lonely creatures, rendered to a solitary existence. They live a life and die a tragedy. Yet, Singh undercuts the sentimentalism of the genre by refusing to vindicate them. Their fated desolation feels like a consequence of a tragic flaw but they are never elevated to be a hero.

In many ways The Song of Scorpions feels like a thematic extension of this gendered duality Singh had first explored in Qissa. It helps that the man at the center bears the same face. Irrfan is fascinating as Aadam; The Song of Scorpions marks the late actor’s last theatrical release and serves as a potent reminder of his genius. He first appears enveloped in darkness yet his eyes glisten. He is never what he seems. Singh imbues Aadam’s character with frightening moral polarity and the actor’s portrayed them like he was both plagued and enlivened by the contradictions. Casting Farahani is an inspired choice precisely because she never fits in. Her liminality, accentuated by accented Rajasthani and light eyes, inadvertently makes her stand out, granting the subtext to Aadam’s infatuation.

At several junctures The Song of Scorpions unfolds like an exoticised depiction of India. The reading is not untrue. Most of the crew members are white. But the story it holds within is unmistakably universal: a man breaks a woman because he feels entitled in love. Singh then goes forth and accords him the tragedy, while reserving the redemption for her.