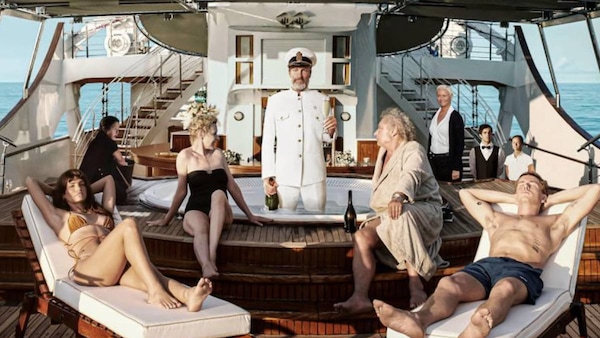

Triangle Of Sadness: What Ruben Östlund's Film Adds To The 'Eat The Rich' Discourse

Last Updated: 11.05 AM, Mar 11, 2023

IN A SCENE from Ruben Ostlund’s Palme D’or winning Triangle of Sadness, a middle-aged woman aboard a luxury cruise ship speaks to one of the female pool attendants. A conversation that begins with cursory introductions gradually devolves into the invocation of privilege as benevolent power. The middle-aged woman urges, and then subsequently commands the attendant to join her in the pool. It’s probably the tensest sequence in a film that punches up, by quite literally punching at its rich characters at times. Ostlund’s point-blank cinema, that swaps subtlety for a more cathartic and direct exposition of will and imagination, is in aggressive form here. The film is also the latest in a canon of cinema and entertainment that frames the rich as imbecilic, entitled specimens who can’t tell their privilege apart from their well-meaning principles. Their charity, in essence, is also their expression of power.

In Triangle of Sadness, Carl and Yaya, a modelling couple, are on board a luxury ship as part of an influencer programme. Ironically, they are not as entitled as their social media profiles pretend to be. It’s the perfect caveat to the sultry, sensual experience of performing luxury as a cultural commodity. Ostlund uses predictable tropes to punish the elite, by pitting their decorated, entitled lives against the groundswell of natural calamity; ultimately, everyone’s privilege is subservient to the laws of nature, the film says. Of late, this has been the motto of a number of characters and films. In Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery, Edward Norton played tech magnate Miles Bron, a hedonistic buzzword-warrior who has ‘invented’ a rare, alternative source of energy. Bron’s antics are sheepish — contrary to the grandiosity of his palatial, somewhat ugly, island.

In the second season of HBO’s The White Lotus, two tech entrepreneurs vacation on an island off of the coast of Sicily. Contrasting with their wealth and their chiselled bodies, their ethical positions are somewhat questionable, at times even dim-witted in their conception. In Apple TV’s The Afterparty, a popular woke musician reunites with his college mates to expose a hilariously petty side of him that is cannon fodder for ‘eat the rich’ variety of humour. In TV’s most popular series at the moment — Succession — the Roys are embattled by the generational takeover of a media empire that has evidently been built on despotism. The rich might be flawed, megalomaniacal even, but what they definitely aren’t, these characters would have us believe, is empathetic, in the original sense of the term.

THERE ARE TWO ASPECTS to the rise of this genre of cinema. The first, at least superficially, concerns itself with the evaluation of growing inequality in the world. The rich have gotten richer, and the poor have gotten poorer. Beyond poetic euphemisms about economic oppression at elite conclaves like the one in Davos, there is little except maybe these imaginary stories that people can look forward to. As opposed to reality, in these stories the cronies are routinely punished. The second aspect must answer a more complex question. Cinema’s escapism allows us the licence of this magnificent, if ultimately pointless repartee, but does prestige cinema around the takedown of the elite actually do anything? Probably not.

It’s a bit rich when you consider that stories built around punishing the rich are also in some ways reserved for them. Triangle of Sadness, for example, premiered at Cannes, a festival inaccessible to the majority of the world. It’s one thing to ignite a conversation, it’s another to universally supply it so it becomes a movement. But for what it’s worth, cinema around the rich has conveyed to us at least, their capacity for depravity and delusion. For decades, philanthropy was used as a socio-political tool to become the bush that we were happy to beat around for generations. Perception automatically gives way to critique. Ostlund uses fairly simple tools, from puking damsels to overflowing commodes, to impress upon us a reassuring sense of justice. All luxury, eventually, is a matter of conceit really, he says. Everyone eats, shits and goes through pain and grief all the same. Everyone, however, doesn’t feel the same amount of hunger.

Triangle of Sadness is two-thirds of a good film, at least for the part where it concentrates on piling misery on the rich without a doomed sense of greater purpose. It’s futile, but it’s far more convincing than the philosophical journey it undertakes for the latter half of the film. Here there are questions about survival, equity among humans when death stares you in the face and the pointlessness of privilege in the wake of universal disaster. It’s at this point that the film stutters, burdened by the need to offer meaning when it has already offered catharsis. The film also, possibly unwittingly, makes the point that only the unanimity of deprivation can make us equal, even if most of us are less equal than others. It’s an idea that could have been left at sea, along with the rest of the film. But at least you can watch some rich men and women really go through hell for the rest of it.