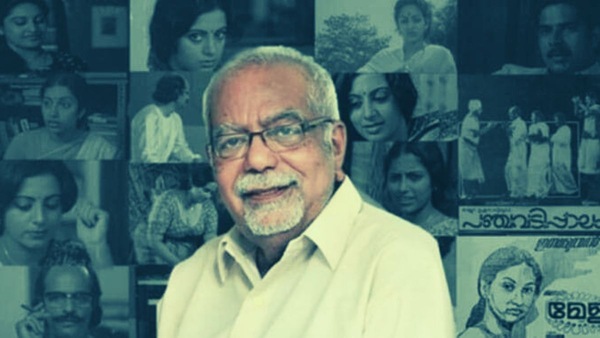

Women In KG George's Cinema Reflected His Own Personality — Stripped Of Artifice

KG George will be remembered as one of the greatest filmmakers in Indian cinema, who perhaps didn’t get the accolades or appreciation he deserved, writes Neelima Menon.

Last Updated: 07.19 PM, Sep 24, 2023

I would have been barely 8 or 9 when I watched Adaminte Variyellu (1983) on television. For reasons an 8-year-old couldn’t fathom, the film deeply disturbed me. It never left me, on the contrary, it made me go back to the director’s other films, and more specifically to the women—flawed, layered, and raw. The three women in Adaminte Variyellu hailed from distinct socio-economic backgrounds struggling to wade through a patriarchal landscape, negotiating with their dignity and identity every single day. If Alice’s (Sreevidya) marriage to the manipulative and abusive businessman Mamachan was built on a labyrinth of lies and betrayals, Vasanthi (Suhasini) is fighting to juggle home and a government job, dictated by an irresponsible spouse and a bullying mother-in-law. Then there is the domestic help, Ammini who is a victim of Mamachan’s sexual abuse. If years of abuse have made Alice impassive and incapable of offering love to her own children, it doesn’t take much time for Vasanthi to lose her mental balance.

It’s been 40 years since the release of the film and no other filmmaker has been able to portray women with such authenticity and realism. And George has been relentless when it comes to depicting broad, rounded, nuanced female characters on screen. What makes the women in Adaminte Variyellu so compelling is his astonishing foresight, stripped of artifice. George shows us the mirror to a patriarchal society that has unwaveringly judged, stereotyped, and marginalised women. Most importantly, he isn’t here to offer you solutions. It never comes across as a shallow documentary on female liberation. And therefore it is doubly impactful and incisive. The climax is given a surreal touch. As Ammini and other women run out of a welfare home, they appear to be running away from the ‘frame’ — freeing themselves from the imposing gaze of society. They “deliberately defy” the directions of the filmmaker and knock down the camera. And George can be seen throwing up his hands in despair.

Even after 40 years, a defiant, sexually liberated Annie in Irakal (1985) who stepped out of her marriage to satiate her libido, remains a celluloid female disruptor. But guess, what’s the catch here? George never moralises her—she is just one of the many immoral characters in the film. Interestingly in the same film, you have a mom who lives up to the mother stereotype, the one who is a mere spectator to her husband and children’s moral degeneration. In Irakal, considered one of his seminal works, he created his own version of the ‘Angry Young Man’—a reaction against the emergency. So there is Baby in the thick of things, an angry victim of corruption, unemployment, and family neglect. The youngest scion of a flourishing Christian family in Central Kerala, he has internalised his fury against his morally deprived father and siblings. Thilakan’s planter who was seeped in patriarchy, later provided inspiration for many such narratives based on Central Kerala, notably the Ranji Panicker alpha male heroes. The timelessness of the film became more evident when Dileesh Pothan did a retelling of Irakal through Joji. However one felt Pothan struggled to add heft to the female characters.

In Mattoral (1985), Susheela (Seema) represents a large section of married women who are forced to follow the patriarchal rules set by their husbands. She has to stifle her desires, dreams, and identity to provide a family for the man. Susheela does it all with robotic precision, till one day she decides to break free. In hindsight, Jeo Baby has clearly borrowed his female lead inspired by Susheela and has simply put a more comprehensive lens into her life in The Great Indian Kitchen, framing her daily drudgery exhaustively. If Jeo chooses to play it safe by holding the woman away from the pedestal of motherhood and moral compass, George smirks at the purists. When Susheela elopes with a mechanic and starts life afresh, she realises that she has jumped from the frying pan to the fire. But even then returning back is never an option for her. Perhaps no other film has depicted emotional abandonment and loneliness in marriages with such nuance. Having said that in the same film, he also shows a couple who happily thrive in a space of equality. Veni and Balu are partners who value each other. When her boss tries to act fresh with her Veni chooses to deal with it personally and doesn’t bother to burden Balu.

That’s why there can’t be a bigger paradox when his wife Selma candidly says in the documentary, 81/2 Intercuts: Life and Films of KG George— “He hasn’t been a great family man. Marriage meant only sex and good food for him.” In a way that explains how he has always portrayed women on screen—with a clear-eyed unemotional lens.

Take his Lekhayude Maranam Oru Flashback (1983), a nuanced, mindful, and detached look at the ruthless world of cinema. It traces the graph of a young starlet (Nalini) who starts her journey at the grimy lanes of Kodambakkam and even when she reaches the heights of stardom, the system never shies away from exploiting her. It takes us on a tour to the desperate, lonely passages of stardom, the struggles, the highs, and the complex relationships. George’s keen eye for detail doesn’t miss a thing—the ego of superstars, the abuse of junior artists, the daily monotony of shooting, and the illusionary grandeur of stardom. When Lekha falls desperately in love with the cocky avant-garde director Suresh (Bharath Gopy), George frames them with cold logical eyes. If Lekha is just one of the many girls whom he willfully exploits, for her this is her last resort from her emotional trauma and loneliness. A film that convinces you to look deeper into the world of cinema beyond the shine and fame.

Even in Mela (1980) that has a dwarf headlining the narrative, he weaves a forbidden love story in the backdrop of a circus camp. The circus camp, the exploitation, and the biases are all sketched finely, along with our appearance-related discrimination.

Right from his debut film, Swapnadanam, a psychological drama, that wowed Adoor Gopalakrishnan, George has always experimented with genres, showcasing his ability to go deeper into the human psyche. In Kolangal, he builds his world in a village, inhabited by people with their own cultural, territorial, and caste biases. The setting is so spot on that the characters look lived in, perhaps a film that led the way to similar realistic village narratives in Malayalam cinema, later tweaked by Sathyan Anthikad with his brand of humour.

Yavanika, one of the finest murder mysteries that unravel in the backdrop of a drama company is perhaps his most remembered work to date. When a tablist of a famous drama company is found dead, the troupe members are suspected. The investigation headlined by a deceptively calm officer, meticulously exposes the characters, leading to an unexpected closure. Soon after Adaminte Variyellu, he did Panchavadi Palam, a political satire, that pivots around a bridge and the corrupt politicians who emerge out of it. It was also his attempt to prove to himself that he could direct a comedy. The film remains his costliest, shot using five cameras.

Ee Kanni Koodi, a well-structured murder mystery that revolved around a sex worker’s murder can be called underrated, or perhaps a better set of actors would have elevated the narrative. But what keeps us invested has to be the unsuspecting emotional heave that gives it the veneer of a tragic romance. While Kathaykku Pinnil (crime thriller) and Elavangodu Desham (period film) can be called missteps from the master.

Not surprisingly KG George never made a film after Elavangodu Desam, but he will be remembered as one of the greatest filmmakers in Indian cinema, who perhaps didn’t get the accolades or appreciation he deserved. No one before or after him created such brilliantly real women on celluloid.