El Conde Review: Pinochet reimagined as a vampire in Pablo Larrain’s edgy, yet toothless satire

The Chilean filmmaker’s latest is stylistically gutsy but rings hollow

Last Updated: 07.54 PM, Jul 13, 2024

Story: Taking a revisionist slant to history, after being indicted of corruption and murder, the Chilean dictator and military general, Augusto Pinochet (Jaime Vadell), fakes his death and flees to a remote countryside, as a vampire out for blood.

Review: Somewhere deep within El Conde, there’s a crackling film. There’s ambition, wit, abandon, and glee in Pablo Larrain’s storytelling, yet the screenplay, which Larrain has co-written with Guillermo Calderon, isn’t as sharp, funny, and biting as it thinks it is. The central conceit obviously is alluring and Larrain isn’t shy of mixing a bunch of wackily imaginative ideas together that result in few feverishly, oddly entrancing passages, but the film suffers from the usual inconsistencies that mar Larrain’s films. This is a film a tad too delighted and smug about its inventiveness so after a point, once the shine of the ideas fades away, the cracks become glaring. The apparent audacity of the film, in all its direct confronting nature as a darkly comic alt-historical, reveals itself as somewhat flaky when Larrain tries to pull us deeper into the denials, tartness and bursts of gruesomeness lining the narrative.

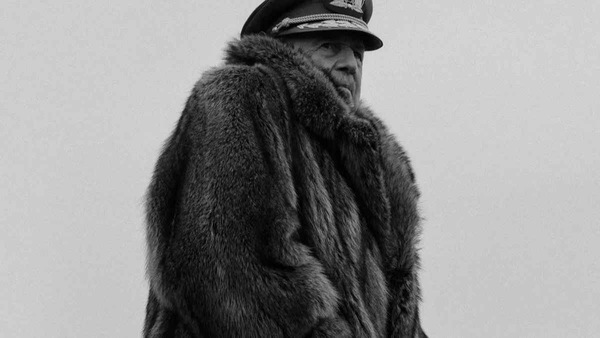

The Chilean dictator, reimagined as a 250-year-old vampire flying all over the city hunting hearts, is otherwise a recluse, settled in the countryside, shot in monochromatic spectral glory by Edward Lachman. The Count, as he likes to be called in private, is tucked away from the public eye, refusing to dwell among those who have morally crucified and charged him with countless instances of corruption and the vilest atrocities. So, once indicted and with his fall from grace, Pinochet faked his death and escaped to his current haunt in a desolate ranch, living with his wife, Lucia (Catalina Guerra) and a Russian butler, Fyodor (an exceptionally scene-stealing Alfredo Castro). The narrator also traces his origins in Paris amidst the French Revolution, stating his desertion of the king, how he licked the blood off the guillotine that took Marie Antoinette’s head, while stealing it from the crypt afterwards. In one of the film’s best lines, Pinochet, who then fled to Chile and took over the “land of fatherless peasants”, is described as looking like a “pimp in the hide of a banana republic mafioso”.

When the film opens, the widely discredited general has expressed his desire to die once and for all and has summoned his five children. Not all of them were willing to show up, some lured by the other with the promise of money and assets their father wanted to dole out. As the wry English narrator (Stella Gonet) notes at a later point in the film, what the Count primarily achieved was turning them into “heroes of greed”. Larrain relies on the age-old storytelling hack – the old father gathering his children together with the purported intent of disbursing his wealth. A supposed accountant, Carmencita (Paula Luchsinger) also appears, ostensibly tasked with finding the scope of Pinochet’s fortunes, stacked away into numerous secret bank accounts in foreign countries under several aliases. As she interviews Pinochet’s wife and children, the dizzying scale of his money laundering is brought to the fore. While Pinochet admits to murder, with one of the earliest bits of the voiceover mentioning the former Captain-general’s particular distaste for the blood of workers (a not-so-subtle allusion to Pinochet’s orchestrated genocide of thousands of Chile’s rural workers, labour organisation members, etc), he insists he is not a thief. As Carmen grills him with a constant smile, Pinochet claims utter gullibility as to the amassing of his fortunes, alleging he fell prey to the manipulation by Chile’s rich businessmen.

There’s envy amongst Pinochet’s children regarding properties one has gotten which the other hasn’t, but they aren’t the familiar excessively bitterly squabbling kind we are used to seeing within this template. Larrain isn’t interested in extracting drama from petty, catty tiffs among themselves for a larger share of inheritance money. Therefore, none of the children get very distinctive characterisation with Larrain choosing instead to etch out the roles of the butler and wife in greater detail. While Lucia concedes it was she who proposed Pinochet’s betrayal, his engineered coup d’etat that overthrew the socialist President Salvador Allende, the butler, referred as someone who was the “master of torture” in his prime, is passionately devoted to Pinochet, making smoothies for him from the hearts pulped into a blender. The two also happen to be in a romantic liaison which they think Pinochet is oblivious to. Larrain paints Pinochet as desperately holding onto glory, projecting it when he has been utterly stripped of it. He is said to frequent the presidential palace every year in the hope of finding a bust of his installed. “History is unfair”, the narrator articulates his disappointment. This is a man behind countless barbarities, who pillaged the country’s economy but has no qualms about any of it since, as he reiterates, it all belonged to him.

Larrain’s gaze is unsparing but also remains determinedly detached from the subject, even as it trails Pinochet swooping through the skyline with a cape of his own and exhibiting manic streaks of violence. At one point, we watch him smash a woman’s head to a pulp. However, despite the brilliantly considered production design of Rodrigo Bazaes, with a thoughtful attention paid to every fleeting glance at the curios and antiques Pinochet loves collecting, El Conde comes off as ultimately half-measured. Ironically, it is the screenplay, for which the film scooped up a prize at the recently concluded Venice Film Festival, just goes around in circles, prodding a point repeatedly after it has long been established. There are no attempts to deepen any of the thematic enquiries and so do the heart-hunting expeditions become ineffective beyond the jabs of shock.

Verdict: The archness in El Conde’s critique does not cut enough and the exposition, slumped atop aestheticized but unremarkable flashbacks, rankles in its laboriousness. Pinochet has been at the heart of Larrain’s cinema for long; however, this feels like the filmmaker’s blandest, emptiest political comment, beneath the buttressing veneer of Lachman’s visual ingenuity.

WHERE

TO WATCH

Subscribe to our newsletter for top content, delivered fast.