The Boy and the Heron Review: Hayao Miyazaki’s swan song is a calm, elegiac spectacle

This quietly melancholic film ponders elemental questions of life, legacy and growth

Last Updated: 07.12 PM, May 10, 2024

Story: The film follows a young boy, Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki), who after the death of his mother in a fire, escapes 1940s Tokyo in the middle of the war with his father to an estate in the countryside. He struggles to adjust to his new life with his father, stepmother (his mother’s younger sister), Natsuko (voiced by Yoshino Kimura) and a group of elderly ladies who work as housekeepers. It is when he trails Natsuko, who walks off into the woods, guided by a talking heron (voiced by Masaki Suda) that he encounters another world lodged within a desolate tower on the farther end of the estate.

Review: How much wonder is too much? Can its overwhelming presence in a narrative prove counterintuitive instead of dazzling? These questions are inevitable while watching The Boy and the Heron. Unsurprisingly, the imagination on display is gorgeous, spectacular and frequently prone to blurring boundaries between the real and imagined. In Ghibli-land, suspension of disbelief is an immediate demand but it never feels like one. Such is the smooth suppleness with which the landscapes are summoned with an enchanting flow by Miyazaki. The ease with which wonder and curiosity is translated and mapped out through a vibrantly imagined world ensures we clutch onto the thread of Mahito’s quest despite snatches of stylistic familiarity seeping in intermittently.

It is a story where exquisite innocence comes under the attack of malice and evil. Evil, hungry, curious-looking creatures abound like they always do in a Ghibli film. Mahito has to navigate a world with treacherous geography and stacked with unpredictably perilous situations. There are uncertainties and confusions rippling through every path in the journey, a not-so-subtle mirroring of his own individual, emotional dilemmas. His mother’s death has left him unmoored. He is in denial. He is yet to process the lashings of grief. However, his bereavement shows in every crack that slips through his otherwise carefully composed demeanour. He puts up a valiant front but how long can he defer his repressed emotions from taking over?

It is this internal storm that materialises through fantastical abstractions in this epic odyssey. In this secret world, there are all sorts of strange episodes. Soon, we come to discover the bevvy of old female housekeepers of the manor are in some way cognizant about the tower’s mysterious happenings. These women function as affective links among the various temporalities at play. Not only do they have more intricate clues into the past than they’d admit, they are also a grounding connection for Mahito to his earthly, present reality. Even if they can’t be around physically, they appear manifested in dolls the boy encounters in the other preternatural realm. They tether him to what he cannot skirt, pointing to inevitable growth out of pain. He has to square his shoulders and brace for what the future holds.

The tower, which the grey heron sneaks off into, was built by his mother’s uncle. He is said to have been a voracious reader and a bit of an eccentric, eventually losing his mind. One day, he just disappeared without a trace, leaving a book open. The tower has been laid to dereliction. But it holds deep, inscrutable ties with the family’s past. This is why Mahito is strongly advised against exploring its depths though he surrenders to the heron’s invitation.

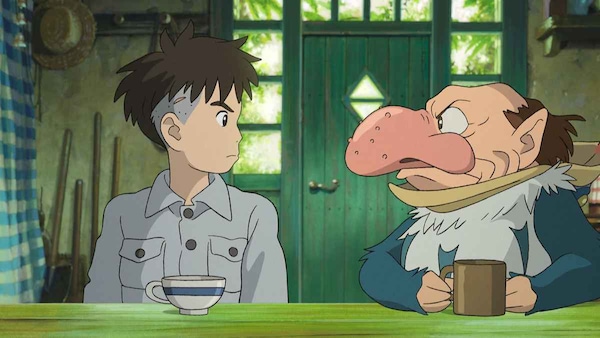

The allure of the invitation draws Mahito into peculiar, vaguely defined lands, sprawling across moors, oceans and cavernous castles that have doors working as portals into varied time frames. It is richly fascinating with its Narnia-esque touches primed to delight even the most cynical viewer. The heron transmogrifies into a small, wizened man with a protuberant nose for a beak. There are armies of vicious, power-thirsty parakeets as well as the most endearing creatures called warawaras resembling soft puffballs, that are basically human souls on the brink of being born. Their ascent skywards isn’t threat-free, as they also become potential feed for pelicans that are faced with increasingly diminishing fish in the sea which would whet their appetite. This illusory, hallucinatory world constructed by Miyazaki is filled with an equal share of kindness and destructive self-hearted agendas. His parting appeal, however, couldn’t be clearer, as Mahito is nudged and emboldened towards building a world of peace, beauty and harmony.

Verdict: At the heart of this fable-like animated adventure, Hayao Miyazaki has woven a tender, moving reflection on mortality, loss, grief and acceptance. The quiet, inner journey of taking the time to emotionally wrestle with all of them may be refracted through visually swashbuckling drama but The Boy and the Heron maintains a subdued wistfulness at its essential core.

Subscribe to our newsletter for top content, delivered fast.