Into The Wild: How A Traveller On Quest To Find Himself, Was Lost

In many ways, Justin Alexander Shetler’s story mines the spiritual subtext attached to modern travel.

Last known photo of Justin Alexander Shetler (R)

Last Updated: 02.36 AM, Oct 03, 2022

Part II.

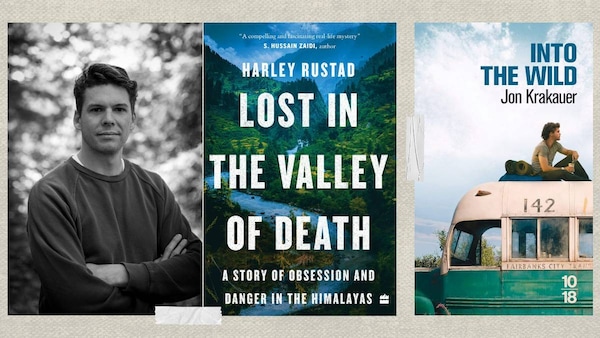

Justin Alexander Shetler arrived in the hills of Kullu-Manali in July of 2016. Shetler had worked a couple of high-paying jobs before quitting corporate life for good and taking to backpacking. He went missing at the end of August/early September that year, having previously shared sporadic updates about his stay in the valley via his blog and social media. Announcing that he was setting off on a 3-4 day trek to Maniktala, Shetler wrote in what would be his last post: “If I’m not back by then, don’t look for me.”

This trail of digital breadcrumbs both helped and hindered journalist Harley Rustad, who traced Shetler’s last journey in his book, Lost in the Valley of Death: A Story of Obsession and Danger in the Himalayas. “There was an enormous resource in Justin’s social media, including videos, timestamps, people tagged in photographs to track down, but that also presented a challenge,” Rustad noted. “What is posted online is always a slightly different version than reality, so I had to question and investigate everything I came across on social media and in some cases found inconsistencies, times when Justin exaggerated a story for the delight of his followers.”

In many ways, Justin Alexander Shetler’s story mines the spiritual subtext attached to modern travel. As far as Shetler had travelled in the outside world, cheered on by his audience, he seemed to desire to travel on the inside. He was tormented by this problem: whether he was going on an adventure or pushing himself because he truly wanted to — or because it would lead to a great story for his followers? “We all want to be truthful in how we present ourselves, online or just publicly. We all want to be honest and to not pretend, and we all know that wonderful feeling when we can be ourselves, who we truly are, and not some fabricated image of what we think is cool or attractive. These were all questions Justin was grappling with to the very end,” Rustad says.

***

The Beatles’ visit to a Rishikesh ashram in 1968 could be seen as a tipping point in the long history of India being regarded as a spiritual destination as opposed to merely a sensory one. The speculative trip, at the peak of a counter-cultural renaissance — Woodstock would take place the next year — would bring a country whose independence was still nascent even if its history and civilisation were ancient, the tag of a mystical destination. Its poverty, its struggles would be fetishised for life-affirming lessons. The “Eat, Pray, Love” model of tourism became a trope.

And as more travellers sought out answers to life’s essential questions — questions of identity and truth and the nature of existence, or the possibility of perfect inner peace — or even sought to escape situations where they might be compelled to confront things they didn’t want to, something known as “the India Syndrome” began to be flagged as a phenomenon. It was coined by Regis Airault, a former staff psychiatrist at the French Consulate in Mumbai, who visited India in 1985. It was meant to be a catchall term describing a spectrum of behavioural changes arising in some foreign (specifically, Western) travellers to India. The Syndrome seemingly manifested as extreme disorientation, a break from their previous lives and selves, and even psychosis. This might have accounted, Airault felt, for some of the disappearances of foreign nationals on Indian sojourns.

Harley Rustad traces these disappearances to something more intangible. “Some go for enlightenment, but many go for their own — sometimes smaller — version of that: a moment of clarity, a path appearing through the mist, a connection to something bigger. They go with questions because they fundamentally believe that India holds the answers,” he notes. “Part of this belief is rooted in truth, in the legacy of figures like the Buddha or Mahavira, but of course part also comes from within the minds of people on the outside looking in, even a problematic Orientalist view.”

***

The mainstream has interpreted the mystery of Parvati Valley in myriad ways, framing it as noir, drama, spiritual mystery and romance. In Tigmanshu Dhulia’s Charas (2004), a cop tries to investigate the disappearance of his friend from London, who has gone missing in the hills around Kasol. He discovers a mystic drug lord, a mafia network and a lot of people who’d rather remain faceless. A decade later, in 2014’s M Cream, a couple of university graduates from Delhi set out to search for a mysterious drug; it leads to chaos and subsequently a humbling form of enlightenment. In 2017, Pan Nalin’s Beyond the Known World followed an estranged couple that travels to India to find their missing daughter, and in the process, reconcile.

It would be easy to write off the travellers who disappeared in the Parvati Valley as “crazy or abnormal” or that they in some way — either because they pushed themselves, or sought extremes — “had this coming”. Or to paint them all with one brush. But that wouldn’t be right. Behind every disappearance was a person, a story — each one unique and tragic and deeply human. “The one central commonality is that each person went there looking for something… on some kind of quest to experience something big,” says Harley Rustad. “And that determined search can be not only challenging and fraught but also very dangerous.”

It would be easy too, to think of Chris McCandless and Justin Alexander Shetler as kindred spirits. And in some ways, they were. Their essential differences are smudged in the minds of casual observers, their quests and fates linking them across an un-spannable distance of time, space and personality. Like the many thousands to whom Chris McCandless’ story has become a touchstone for “living deliberately”, so too does Justin Alexander Shetler’s journey hold significance for complete strangers. Says Harley Rustad: “The more I dug into Justin’s backstory the more I realised that his was a life that spoke to many people, both in their struggles and in their desires and questions... He just took his searching for answers to an extreme.”