Newsletter: Murder On The Reorient Express

The whodunit is decisively back in season, and the genre's prospects couldn't be more promising. Prahlad Srihari writes.

Last Updated: 05.00 PM, Jul 07, 2023

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter Stream Of Consciousness on January 8, 2023. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

THERE HAS BEEN A MURDER. The suspects are figures from the victim’s past. Charged with exposing the link and motive, is the eccentric sleuth galvanising the intrigue. There may or may not be the odd fake-out and twist in the tale before the unmasking of the killer. Who doesn’t love a good whodunit? That the genre ever fell out of favour is baffling.

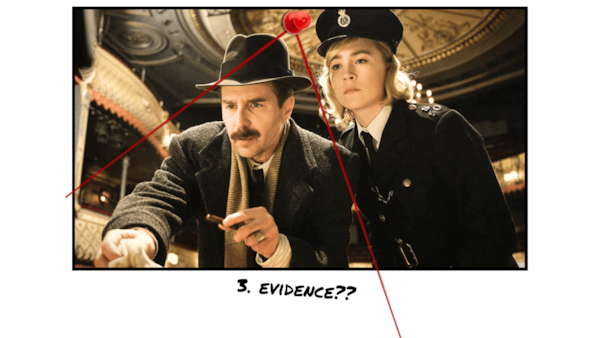

Thank Christie the whodunit is back in season again. There have been quite a few over 2022 on the big screen and small. Only Murders in the Building returned for a second season. The Afterparty saw a high school reunion end in tragedy. Glass Onion, the Knives Out sequel out now on Netflix, continues the grand tradition of The Last of Sheila and Evil Under the Sun. The Queen of Crime was even a character in See How They Run, where Sam Rockwell and Saoirse Ronan star as mismatched police officers investigating the murder of an American film director backstage, during the 100th performance of The Mousetrap.

Five years after Kenneth Branagh made a mockery of Hercule Poirot in Murder on the Orient Express, he botched up Death on the Nile. The first sign of trouble was the opening scene — an origin story of the Belgian sleuth’s moustache. Those who jumped ship right then and there: Know that the moustache is given more depth than most of the characters. A starry cast of Annette Bening, Russell Brand, Ali Fazal, Gal Gadot, Armie Hammer, Rose Leslie, Emma Mackey, Sophie Okonedo, Jennifer Saunders and Letitia Wright barely made a splash.

David O Russell’s Amsterdam was another bloated whodunit guilty of failing its A-list cast (Christian Bale, Margot Robbie, John David Washington, Chris Rock, Anya Taylor-Joy, Robert De Niro, Taylor Swift, Rami Malek, Zoe Saldaña, Mike Myers, Michael Shannon, Timothy Olyphant, Andrea Riseborough, Matthias Schoenaerts, Alessandro Nivola... phew!).

Whodunits present the opportunity to go big with ensembles — gather a whole circus of talent to play the suspects. That’s part of its charm as long as that opportunity isn’t squandered, as it is in Amsterdam, Death on the Nile and See How They Run. In contrast, Glass Onion and Bodies Bodies Bodies (a whodunit for the TikTok generation written by Kristen Roupenian of “Cat Person” fame) give everyone the room to shine, and are all the better for it.

IF THE GENRE has enjoyed a resurgence, it’s because it has a morbid appeal, more so now as its vision of a society teetering on the edge of chaos feels awfully familiar. The lockdown would have been an ideal pressure-cooker set-up for a locked room whodunit. A domestic conflict, compounded by pandemic frustrations, boils over. Any part of the house — from the kitchen to the bedroom to the bathroom — could be a death trap. There is no shortage of weapons lying around to pull off the perfect crime.

Whodunits come in different shapes, sizes and schemes. Some are interested in crime purely as a puzzle to be solved by the detective who turns observation and deduction into pageantry. Some treat crime as an individual choice rooted in benefit-cost ratio. Some approach crime as a social determinist would: consider the external factors that put the knife in the killer’s hand. A lot of the modern whodunits are more conscious of class and racial anxieties. Tethering the story to a recognisable reality gives the mystery a socio-economic edge.

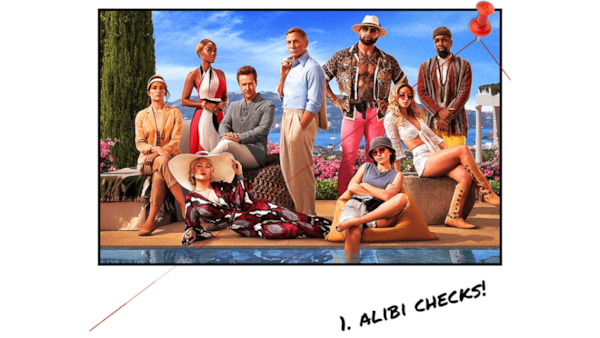

In Knives Out, the presence of Ana de Armas’ nurse underlines the entitlement of the rich and dysfunctional. In Bodies Bodies Bodies, Maria Bakalova’s working-class character serves a similar function. Where Knives Out had old money in its sights, Glass Onion targets new money: a motley crew made up of a tech billionaire, an influencer, a fashionista and a politician. On the task of taking them down a peg or two is Daniel Craig’s Benoit Blanc, armed with a wit that rolls off his Southern drawl.

The modern whodunit is more self-reflexive, employing the mechanics of the genre with heavy irony. In Glass Onion, a billionaire (Edward Norton) throws a murder party for his friends, all of whom resent him. The Zoomers of Bodies Bodies Bodies decide to ride out a hurricane by playing a parlour game that goes horribly wrong. See How They Run and Only Murders in the Building go one step further: questioning the morality of murder mysteries, especially when based on real-life stories. Yet, even if you were to consider both as any sort of indictment of pop culture’s obsession with murder mysteries, they are also very much love letters to the genre.

SEE HOW THEY RUN loops its tangled murder mystery with an indictment of the whole entertainment industry. The victim is an American director looking to adapt The Mousetrap in 1950s London. The suspects are the cast and crew of the production, which includes fictionalised versions of the real-life husband-and-wife pair of Richard Attenborough and Sheila Sim. The killer turns out to be an usher who had lost his brother as a child, in a high-profile case of domestic abuse and murder. The case, it turns out, inspired Christie’s play. But when the play became a hit, the usher was sick of seeing his brother’s tragedy exploited as entertainment. So, he killed the director before the story could continue to live on as a movie.

During the climax, when Dennis asks Christie to stop the production, she apologises that she can’t in the name of freedom of expression. “I’m a writer, you see,” she says. “I can’t be told what to write or what not to write. It would be a denial of one’s freedom.” If the cast and crew apologise, it is to assuage his anger and survive the night. The cops intervene before he can kill Christie or the others. The movie ends with another performance of The Mousetrap, without ever reckoning with the reality behind the killer’s motive. The killer in Season 2 of Only Murders in the Building too turns out to have a connection with an earlier murder which was the subject of a popular podcast. The connection being she was the presumed dead subject who faked her own death to start a new life. Only, she becomes overcome with ambition.

Only Murders in the Building can be quite thoughtful, when it comes to examining our consumption of true crime stories and our vicarious relationship with the real people documented in them. The show offers precious peeks into the private lives of its characters to humanise them. Characters are treated as mysteries in themselves waiting to be understood. It resists the genre’s tendency to flatten people into archetypes: the killer, the suspect and the victim. Season 1 centres a deaf character’s POV in a near-silent episode which exposes his inner desires as well as a dark secret. Season 2 recasts Bunny Folger, Arconia’s cantankerous board president, in a whole new light. On the switching of POVs in an episode, we learn she was what was keeping the apartment building from falling apart.

When the podcast trio (played by Martin Short, Steve Martin and Selena Gomez) are celebrating their cracking of Tim Kono’s case, Bunny brings a bottle of champagne, hoping to join them. But they are oblivious to her intentions and fail to invite her in. When the door closes on her face, it is a heart-breaking moment because she is killed the very next instant, on returning alone to her apartment. By foregrounding Bunny in the episode, the show suggests how the flattening of trauma into spectacle can distance us from real pain and make us blind to it even when it is staring right in our faces.

Compare how Short’s Oliver treats the suspects in Season 1 to how Tiffany Haddish’s Detective Danner does in The Afterparty. Oliver, in a fantasy sequence, lines up the suspects like they were auditioning for a role in a Broadway production. “Congrats on making it this far. You should all feel very proud indeed, but as you know there can only be one ‘Tim Kono’s murderer.’ I’m looking for motive; I’m looking for means; but most of all, I’m looking for moxie.”

Danner, on the other hand, requests each suspect to tell their story in their own words. “We’re all stars of our own movie,” she says. “As a part of my process, I like to talk to each person. I want to hear your story. I want to hear your mind movie. If you gather all that together, you can get at the truth.” Each suspect gets their own episode, told from their own perspective, in genres that reflect how they see themselves. The idea is characters can’t be reduced to a quirk if it’s their own POV, rather than that of an outsider looking in. This signals a change in how characters are written in some of the modern whodunits and how they deal with the ethical quandaries of murder mysteries.

THE SKELETON OF THE NARRATIVE is the same in Knives Out and Glass Onion: murder leads to madness leads to mayhem leads to a power reshuffle. The set-ups pay off on both occasions. Johnson establishes himself as a master at turning the whodunit and its established formalisms on their head. In Knives Out, the murder turns out to be not a murder but a needless suicide. The nature of the mystery in Glass Onion too is fluid. He doesn’t quite invite the viewer to play armchair detective like Christie did. But even if the mystery practically solves itself, watching the drama unfold is never less than electrifying. The writing gives the whodunit mechanics a satirical edge, relying on the spectacle of dialogue rather than the withholding of detail. Johnson may be nostalgic for the '70s, borrowing cues from that Golden Age when Columbo was on TV and The Last of Sheila in theatres. But he retains his own distinct sensibilities for the movies to never feel like mere contemporised facsimiles. Most of all, he knows when to play it straight and when to wink at the audience.

It’s this sense of timing and balance that See How They Run director Tom George and writer Mark Chappell could have benefited from. The movie opens with the director Leo Köpernick (Adrien Brody) calling The Mousetrap a “second-rate murder mystery” before bemoaning the predictability of the whodunit. “You’ve seen one, you’ve seen ‘em all,” he suggests. At one point, Oyelowo’s screenwriter character criticises flashbacks: “They are crass, lazy, and they interrupt the flow of the story. In my opinion, they are the last refuge of a moribund imagination.” The next scene is of course a flashback. The movie may think it is clever with its wink-wink humour, but it is no doubt caught in two minds: between nostalgic reverence and postmodern defiance.

Pointing out conventions doesn’t equate to subversion. See How They Run is a case in point. Not pointing them out doesn’t equate to compliance. Glass Onion is a case in point. Bodies Bodies Bodies is another, as it rewrites the whodunit with slasher conventions. A group of friends get together for a hurricane party at a remote mansion. Things go wrong after a parlour game fuelled by alcohol, cocaine and no WiFi. Tensions rise. Buried feelings resurface. Loyalties are tested. Clique dynamics take shape. Before throats are slashed open, everyone is cutting each other apart with hurtful remarks. The parlour game makes way for blame games in a comedy of errors.

Comedy is so essential to the pleasures of the modern whodunit. With a cast made up of comedy actors like Tiffany Haddish, Sam Richardson, Ilana Glazer, Ben Schwartz, Ike Barinholtz, Jamie Demetriou and Dave Franco, The Afterparty fares better as a comedy than a whodunit. The same goes for Only Murders in the Building. The podcast trio may share an endearing dynamic. But if the show remains unmissable TV despite its often-unengaging mystery, it is because of Short’s over-enthusiastic theatre lover Oliver Putnam.

Superbad and Adventureland director Greg Mottola returned from a six-year hiatus with the year’s most enjoyable murder-mystery comedy in Confess, Fletch, which somewhat flew under the radar. Jon Hamm’s charm offensive works wonders in the role of investigative journo Irwin Fletcher, the character from Gregory Mcdonald’s mystery novels who was popularised by Chevy Chase on screen. Expensive paintings go missing in Italy. A body is found in a Boston apartment. When Fletch is named prime suspect, he must prove his innocence with cops on his tail.

Hollywood simply doesn’t make movies like this anymore. It’s true: we all complain about studios making too many sequels and reboots. But few will say no to more Knives Out and Fletch movies. Johnson and Mottola are more than worthy successors to Christie and Mcdonald. By the end of their careers, Craig and Hamm could come to be remembered for playing Benoit Blanc and Irwin Fletcher just as much as, if not more than, James Bond and Don Draper. There is no denying the future of the murder mystery genre is in capable hands.