Newsletter | Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai: Manoj Bajpayee Drama Is A Defense Of God Against Man

This is #CriticalMargin, where Ishita Sengupta gets contemplative over new Hindi films and shows. Today: Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai, on ZEE5.

Last Updated: 03.20 PM, May 24, 2023

This column was originally published as part of our newsletter The Daily Show on May 24, 2023. Subscribe here. (We're awesome about not spamming your inbox!)

***

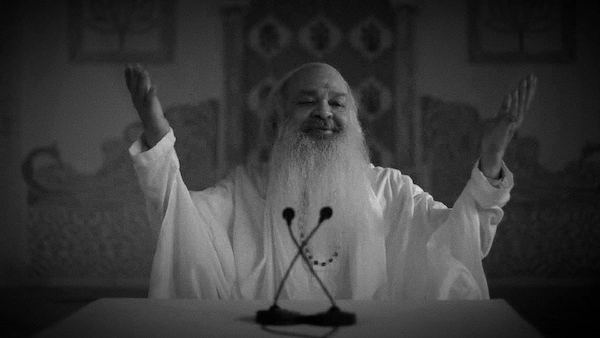

IN Apoorv Singh Karki’s Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai, a lawyer fights against a godman accused of raping a minor. If the premise reads like a news bulletin distinctive to India, a country abound with morally ambiguous demigods, then the details dispel all doubt. The film opens in Delhi and the year is 2013, the advocate’s name is PC Solanki and the case is being fought in Jodhpur. Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai is a fictional retelling of the high-profile Asaram Bapu case in which the religious leader was charged under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act and the Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act for raping a minor.

The film follows a trajectory of which much is in the public discourse: The contentious arrest of the godman in 2013, followed by his followers’ protests, the deaths of key witnesses and the five-year-long legal battle that ultimately led to his punishment. The style is tellingly procedural. Karki designs the outing as a courtroom drama where the tragedy is alluded to and briefly depicted. It opens outside a police station in Delhi where a 16-year-old girl, Nu Singh, accompanied by her parents, lodges a complaint against a famed godman. She states that when she visited the Baba’s ashram on the advice of her parents, both devotees, the godman took her to a room under the pretext of exorcising the ‘evil spirits’ besetting her, and then touched her private parts. Post this, the story dives straight into legality with the narrative leaning on the portrayal of an upright man and his perseverance for justice amidst all the odds stacked against him.

On paper, this shift in slant is clinical. It serves even better here because Karki’s previous venture, the Amruta Subhash-starrer Saas Bahu Achaar Pvt. Ltd, was mired in stilted gender insights. The coming-of-age tale of a woman was presented via men’s interpretation of it, which resulted in rousing presentation of even basic acts… as if the creators involved in the series — all men, much like this film — were perpetually surprised at a woman’s fortitude. Hence, Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai’s decision to not delve into the plight of the woman or the shame she had to undergo feels as orchestrated as informed.

The troubling bit is even this time the filmmaker does not temper his inclination for heightening emotions. Thus, ever so often the background music blasts during crucial moments in the court or even otherwise, revealing the film’s intent to make you feel something without trying to invoke it. It becomes particularly jarring in a pivotal moment shared between the lawyer and the girl where excess is bartered for quietude. It also does not help that this lack of trying shows even in the writing.

Granted the incident the film is portraying is widely known, but for a courtroom drama, Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai initiates very little tension. One can argue that the dry style mirrors the laborious process of pursuing justice in this country, especially when the power balance between the people involved — the accused and the survivor — is so vast. But the feeling that one gets on watching the film, is that the method was chosen more for valourising the lawyer at the centre — a noble idea that somehow feels unearned.

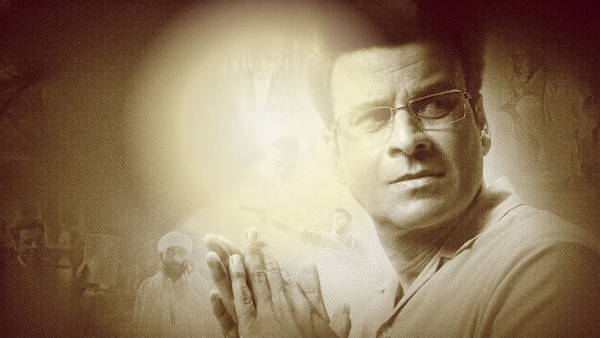

That said, having an actor like Manoj Bajpayee essay the role smooths over a lot of creases. Bajpayee has come to inhabit complete control over his craft, which undoubtedly is cultivated by effort but unfolds effortlessly. His courtroom scenes assume a mesmeric quality precisely for the way he moves his hands, bends his head. As Solanki, a religious man living with his mother and son, Bajpayee brings in a fragility which feels like his own making. Every time he says something in Hindi, the diction is so perfect, the Rajasthani accent sounds so musical, that it is difficult not to be taken by him. In fact, I am even willing to overlook the fact that his son and he refer to each as ‘buddy’, something I count as a red flag in my book. But it is difficult to overlook the creators’ lethargy in not depicting the passage of time. The film tells of a court case that ran for five years. But by the time Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai concludes in 2018, Solanki’s son hasn’t grown an inch nor has he aged one bit. This might sound trivial but details such as these enhance tales of prolonged justice. As reference, think of the impeccable detailing in Prashant Nair’s show Trial by Fire.

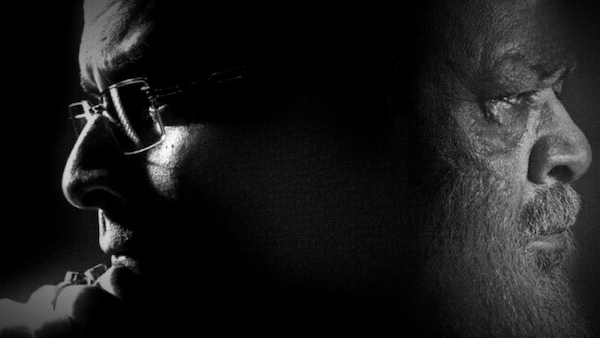

Notwithstanding this, the film is most compelling in the details it lends to Solanki’s character. It would have been only too convenient to write him as the single father of a daughter, the context of his offspring’s gender providing the subtext to his willingness to fight for another girl. Sirf Ek Bandaa Kaafi Hai, however, abstains from doing that, granting a nice touch of highlighting his agenda-less tenacity. The other rewarding bit is depicting him as a devout Hindu, a religious man who believes in god. Bajpayee is shown to be a believer in the ritualistic idea of worshipping. Having someone like him stand against a godman is an unlikely arrangement for the way it circumvents stereotypes. Solanki’s fight then becomes an opposition in the most fundamental sense of the word, where he is contending with what religion is made out to be by some people and not what it actually is.

It is an interesting dynamic which assumes greater meaning when placed within the socio-political landscape of India where the culture of reverence is often co-opted for self-serving interests. Solanki’s closing monologue for justice becomes a louder plea of a believer who underscores the thin line that separates devotion from dogmatism without questioning faith. Given how rapidly this distinction is fading, such a reminder feels both topical and radical.