Literarily Speaking: Pinjar (2003) – A woman’s place in the world

Chandraprakash Dwivedi’s adaptation adds other points of view to popularise Amrita Pritam’s Partition novella

Last Updated: 11.28 AM, Mar 22, 2024

In our column, Literarily Speaking, we recommend specially curated book-to-film adaptations that will leave you spell-bound

Poet and writer Amrita Pritam’s Punjabi novella, Pinjar, is set at the time of the Partition of India. Young Puro belongs to a Hindu Sahukar or moneylender family in a village called Chatto. Her marriage is arranged with a young man called Ramchand from Rattowal village, and Puro yearns for Ramchand, anticipating the day she will be his bride. As per the convention of that time, her brother is betrothed to Ramchand’s sister.

But just before her wedding, Puro is abducted by a Muslim youth called Rashida. After 15 days of captivity, he confesses that he has always been in love with her, and her abduction was to settle old scores between her people, the Sahukars, and his people, the Shaikhs.

When Puro escapes and reaches her village, her distraught parents tell her that they cannot take her back lest the Shaikhs retaliate. Puro feels abandoned by her family, and resentful that her betrothed Ramchand did nothing to rescue her. Rashida finds her and marries her. They move to a different village, and it is here that her new name, Hamida, is tattooed on her arm.

Even as Rashida takes loving care of a pregnant Puro/Hamida, she resents him for wrecking her life. But after she gives birth to a son, her hatred for Rashida and their child begins to soften.

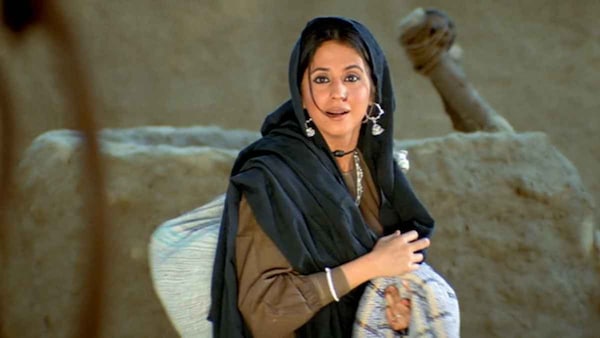

Hamida meets three women who transform her worldview. Hamida nurtures an emaciated 12-year-old Hindu girl called Kammo who visits the village. But this bond is sundered when Kammo’s overbearing aunt finds out. Hamida meets young Taro who is outspoken among the women but has no agency in her difficult married life.

An unnamed mentally unhinged woman moves into an abandoned shed in Hamida’s village, and roams semi-naked, caked with dust. When she is found pregnant, the women of the village are aghast that a man could be heinous enough to take pleasure from a woman of unsound mind.

Compared to these three women, Hamida’s life appears fortunate. While the beginning of Hamida’s marriage was a violent wrenching away from the familiar, Hamida realises that many women endure isolation and alienation in society, and even within their home and their marriage.

One day, Hamida comes across the mentally unstable woman's dead body, and her still-alive newborn child. Hamida nurses the infant, but in time, the Hindus of the village object to the child being fostered by a Muslim, claiming his mother was a Hindu. The child is taken away by them but is soon returned to Hamida in an impoverished state. Under her care, the child thrives once again.

The region is in the throes of the Partition - people slaughtered, women abducted and raped, and families undertaking the long arduous journey to the other side of the border. Hamida meets Ramchand, once her betrothed, who is among the dispossessed. She learns that Ramchand married her sister, who is now with her parents. Meanwhile, Ramchand’s sister, Lajjo, who was wed to Hamida’s brother, has gone missing. Hamida beseeches Rashida to help find her sister-in-law, Lajjo. Rashida suspects that she is among a group of girls abducted and detained in Rattowal itself. Hamida eventually finds a listless young woman being held captive, with the name ‘Lajjo’ tattooed on her arm. Hamida persuades Rashida to abduct her, secretly instructing the fearful Lajjo to trust the man who wears Hamida’s ring. With Lajjo’s abduction, the weight of guilt on Rashida’s conscience lifts. He arranges to meet Ramchand and Hamida’s brother at Lahore, and there, Hamida finds closure by sending away Lajjo as one would, a daughter to her married home. Hamida’s brother asks her to return to India with him, but she firmly tells him that she now belongs with Rashida in Pakistan.

Movie adaptation

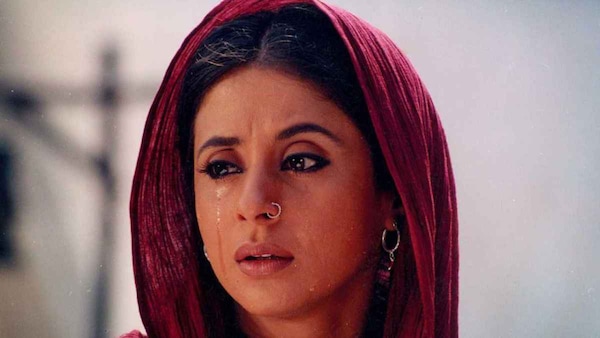

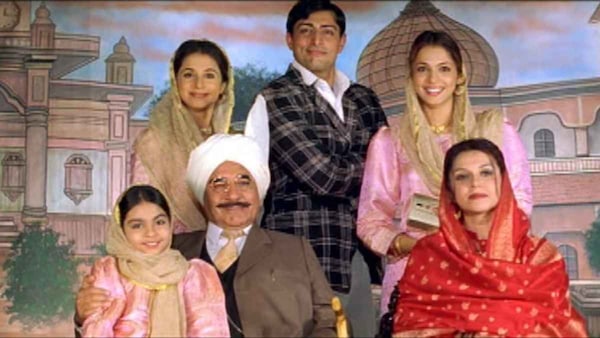

Chandraprakash Dwivedi’s adaptation builds on the Ramayana reference that Pritam only alludes to, fleshing out some characters, leaving out some, and adding others. He depicts Puro (Urmila Matondkar) as a vivacious young woman who lives in Amritsar in a family where it is socially acceptable to pray for the birth of a male child, and for girls to be trained from a tender age to keep house.

Dwivedi adds depth to the character of Puro’s brother, Trilok (Priyanshu Chatterjee), who remains unnamed in the novella. Puro’s engagement with Ramchand (Sanjay Suri), arranged by the elders, is elaborated upon, and we even meet his sister, Lajjo (Sandali Sinha) who will marry Trilok. Puro sneaks a peek at Ramchand and begins to daydream about him.

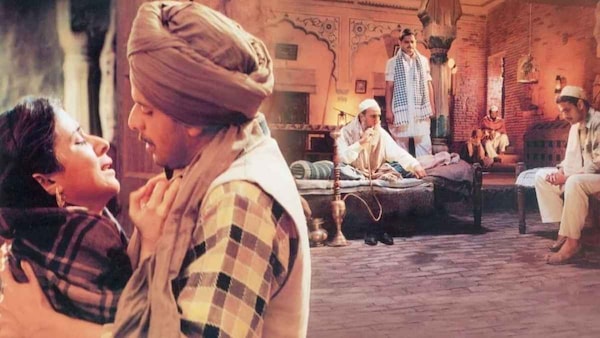

Puro accompanies her parents to their ancestral village of Chhatwani and it is here that Rashid (Manoj Bajpayee) becomes besotted with her. Puro has nightmares about Rashid but hesitates to tell anyone about it. Rashid’s people taunt him that he merely stalks her, but does not act on his desire for her. He abducts Puro, but is soon filled with remorse.

Just as in the novella, Puro begs Rashid to let her go, but Rashid confesses his love for her and expresses his helplessness. He promises her that once things settle down, he will take her to meet her parents. When Puro escapes and reaches her ancestral home, Rashid is proved right. Instead of the tears she would have shed during her ‘bidai’ as a bride leaving her childhood home, Puro's keening is for the family that regards her dead.

Puro’s father is summoned by Rashid’s people, and informed that with Puro’s abduction, their old score has been settled. Puro’s brother is filled with rage but is prevented from reporting it to the police lest the family’s reputation is ruined. Trilok’s will, juxtaposed against his father’s helplessness is not in the novella, where the narrative stays with Puro.

While Trilok marries Ramchand’s sister Lajjo, Puro’s parents offer their other daughter, Rajjo to take Puro's place as Ramchand’s bride. But Ramchand demurs and remains unmarried, unlike in the novella.

The abandonment by her family turns Puro from a still-hopeful young girl to a world-weary woman. She decides to throw herself into a well but is saved by Rashid who weds her, even as she daydreams of Ramchand as her groom. Rashid’s extended family forces her new name Hamida to be tattooed on her arm, while in Amritsar, her sister-in-law Lajjo has her name tattooed on hers.

Much to Rashid’s anguish, a pregnant Puro/Hamida regards the child as the unfortunate result of a violent union. Unlike in the novella, Hamida suffers a miscarriage. The mentally unstable woman who wanders the village dies at childbirth. With Rashid’s support, Hamida takes charge of the child. After 6 months, the Hindus arrive to forcibly take the child away, and Hamida loses one more loved one. Unlike in the novella, the child is never returned to Rashid and Hamida.

When riots begin in the region following the Partition, Rashid abstains from violence. He explains to Hamida that they are now in Pakistan and that the Hindus of the region will go to India.

While the novella speaks of the girls Kammo and Taro, Dwivedi’s movie introduces the character of a Hindu girl whom Hamida rescues. The girl recounts the horrors wrought upon the women by the mobs who treat them much like the land they seize. When Ramchand’s group passes through her village under the protection of the Punjab Boundary Forces, Hamida entrusts him with the girl’s safety. This scene serves little purpose apart from a meeting between Ramchand and Hamida where the latter learns of her sister-in-law, Lajjo’s abduction, and brings attention to the tattoo.

Hamida begs Rashid to help her find Lajjo, and they go to Rattowal under the pretext of visiting a shrine. When she recognises Lajjo from her arm tattoo, Hamida enlists Rashid’s help in abducting her. The ring from the novella is retained in the movie, and in a poignant scene, Rashid calls Hamida by her old name, Puro, and assures Lajjo that he has made all arrangements to ensure she returns home.

When Rashid arranges for Trilok and Ramchand to visit Lahore under a government initiative to return abducted young girls to their families, Hamida learns that Ramchand has stayed unmarried, and is willing to marry her. The contrast between Ramchand and Rashid is not lost on the latter. Hamida realises that Rashid is not near her, and she becomes distraught. When she finally finds him, she tells him that this is her home. After being abandoned by her family, losing her child, and losing her foster child, Puro/Hamida makes her choice to be with Rashid in Pakistan. The movie ends with a rendition of Pritam’s famous poem, Ajj Aakhaan Waris Shah Nu, where Pritam asks Waris Shah, the poet who immortalised Heer Ranjha’s tragic love story, to bear witness to the tragedy unfolding in his land due to the Partition.

The Ramayana references

In the novella, apart from the obvious parallel of an abduction, and Ramchand’s name, the main reference to the Ramayana is when Hamida assures Lajjo that she can trust the person who bears her ring (much like Sita would recognise Hanuman in Lanka as a messenger of Rama by the signet ring). Pritam, thereby, gives Rashida, the abductor, the opportunity to redeem himself as the enabler of a woman’s emancipation. She, however, doesn’t burden Puro/Hamida with Sita’s identity.

In the movie, apart from the above Ramayana reference, there are many other references that neither reinforce the epic’s themes nor do they offer an alternate point of view. Ramchand remains unmarried, much like Rama from the epic, who remains devoted to Sita even after her trial by fire. There is a throwaway reference to Surpanakha by Puro’s flirtatious friend addressed to Ramchand. Puro sights Ramchand and admits that for this Rama, she would not only undergo exile but also the trial by fire. Ramchand and his sister sing a bhajan about Seetha’s predicament where if she survives the trial by fire, she will be considered a goddess, but if she is burnt, a sinner. The narrative leaves out the problematic sections – that the trial by fire was a decree by Rama himself, and that of the binary of goddess and sinner.

Title and relevance

The word ‘Pinjar’ in Punjabi, translates to ‘skeleton’. Interestingly, in many Indian languages, the word for ‘skeleton’ is a variation of the word for ‘cage’. Although Pritam refers to the mentally unstable woman as 'pinjar', she perhaps refers to women in the society of that time as caged beings, with the cages sometimes being their own families. Much like property, the woman was commoditized - owned, sold, passed on or seized – and her identity is in relation to the man in her life.

In the end, Pritam’s Pinjar is about Puro/Hamida realising that she is a victim of a larger overarching system of patriarchy and politics that strips women of their agency. Much of Puro/Hamida’s character growth and Rashid’s redemption come from the agency she exercises. While Dwivedi does indeed add dimension to Rashid’s character, perhaps implying him to be as much a victim of patriarchy, it is Pritam’s story, and she chooses to keep the focus on Puro/Hamida.

You can watch Pinjar here.

(Views expressed in this piece are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of OTTplay)

(Written by Saritha Rao Rayachoti)